Mark Donegan, of Redwood Valley, California,

says, "I'm fidgety because of pain; my body's

telling me to move, so I do it everywhere on the

bus, sitting around with friends,wherever I am."

Donegan, 36, is recovering from a very painful

back problem that nearly crippled him, a

herniated inter-vertebral disk in the lumbar

spine. He weaned himself off heavy medications

offered by physicians and chose instead to heal

himself through natural movement, the key

element in self-healing.

Moving in a natural way frees you. It is well-

known in movement science that the skilled

performer has more degrees of freedom

(movement choices) than the novice. When you

look at a film of Fred Astaire and Ginger

Rogers dancing, you feel their looseness, ease

and pleasure in movement. It says a lot about

our culture that they had to work hard to make

it second nature to move easily. As they dance,

you see that their muscles work only as hard as

appropriate and don't substitute for the work of

other muscles (the principle of isolation).

Without tensing up the abdominals, they move

loosely from their center (the navel area). It's

much less effortful, energy-costly and wearing

than the "normal" movement patterns most of us

exhibit, which eventually create chronic health

problems.

Athletes and dancers don't necessarily move

naturally; when they use the body as a tool, they

block out a sense of its problems and needs.

Natural movement comes out of kinesthetic

awareness, a deep, subtle sense of movement-of

breath, energy, blood and other fluids throughout

the body, of joints finding their full range in all

planes, of muscles becoming supple, strong and

balanced. You become aware of the body's

specific need for movement at any given time.

Natural movement healsㅡit increases circulation,

reduces inflammation, creates strength,

endurance and a sense of well-being, and

nurtures every part of the body, including the

joints. Helping the client restore natural

movement is essential in working with joint and

spine problems.

Unfortunately, most people move in an

unbalanced, constricted way. This kind of

movementㅡpatterns of overuse, under-use and

misuseㅡis damaging to the joints, including

those of the spine. Doing more of it in the name

of "exercise" will only make you worse.

We suggest reviewing the article, "Movement is

Life," (Issue #60, March/April 1996); those

exercises and principles are helpful for people

with back problems.

A back problem years in the making

When Donegan was 29, his job required him to

climb up and jump down to fetch items from

grocery stockrooms many times a day. "We were

expected to move fast," he said. He woke up one

morning feeling that his left leg didn't want to

move. A chiropractor diagnosed herniated disk

(also known as disk prolapse or slipped disk), a

complication of degenerative disk disease. Like

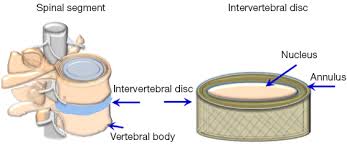

cartilage, intervertebral disks in the spinal

column are believed by physicians to degenerate

inevitably, beginning at early adulthood. As a

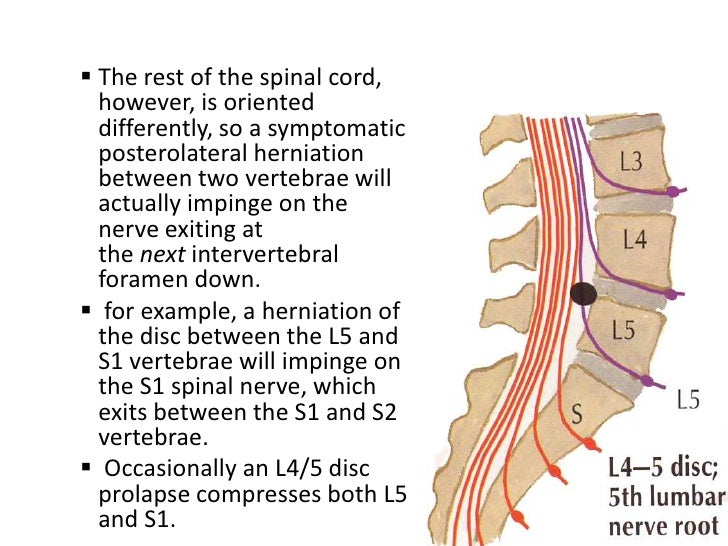

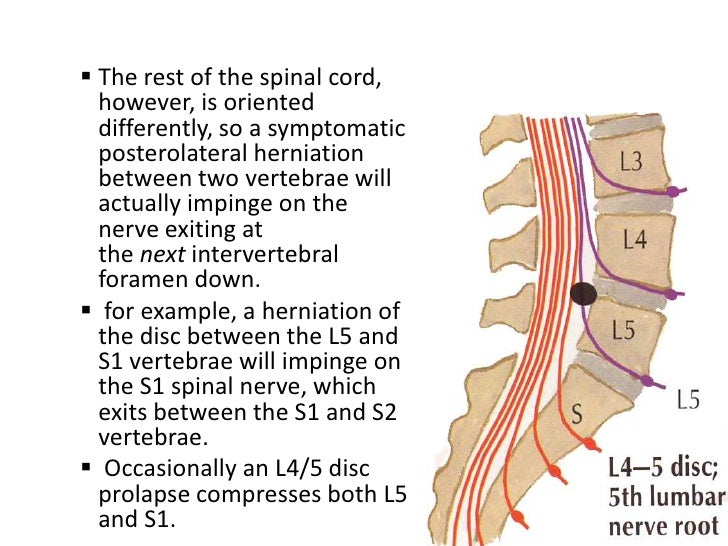

complication, the disk may herniate or rupture. A

strong ligament keeps it from bulging directly

backward, so it moves posterolaterally, where it

may compress or stretch a spinal nerve root.

Posterolateral: situated on the side and towards

the back of the body. The result is radiating pain,

muscle weakness and sensory losses, always

along the distribution of the spinal nerve. This is

actually one form of sciatica, which can also

begin with compression further down the nerve.

Most prevalent in young men, herniated disk is

rare after middle age, because the disk has lost a

lot of its mass.

Four months of chiropractic treatment only

aggravated the problem. Donegan tried physical

therapy, and it worsened again, until muscle

spasm and pain prevented movement in the leg

altogether.

Two surgeries brought only temporary respite.

In the first operation, part of the disk and of the

bony arch around the spinal cord were trimmed

away; in the second, more of the disk was

removed and two vertebrae were fused together.

After the second surgery, new symptoms came

onㅡnumbness in the left leg, high blood pressure

, irregular heart rate, bowel and bladder

problems. The right leg had been the anchor for

crutch walking; now he lost sensation and

movement in it, too.

"I was looking at a wheelchair next," Donegan

said. "I was depressedㅡmy whole world was

falling apart. The pain gave me nausea and

vomiting. Let me tell you about extreme pain.

You can take it for a day and it's okay. Two days,

and you start getting tired of it, but on the third

day, you don't have anything left. You're not you

anymore."

Another surgeon told Donegan he could remove

the rest of the damaged disk and stabilize the

region with bone transplants and internal braces

and screws. There would be a new source of pain,

however, from the braces. The surgery restored

his ability to walk but left his back swollen and

painful, and "I had nothing left, no will,"Donegan

said. At a pain clinic in Mendocino, California,

Donegan began working with massage therapist

Audrey Ferrell, who practices neuromuscular

therapy. Ferrell gave him massage and movement

exercises. Gradually his pain abated enough that

he could resume his favorite activity, bicycling.

''I gave the doctor back all of his prescription

pain medications; the only thing I kept was over-

the-counter ibuprofen." A year later, Ferrell

brought him to Meir Schneider. " Meir glanced at

me and told me where my pain was," Donegan

recalls.

While Schneider's evaluation seemed fast and

effortless to Donegan, he used, as always, the

method he teaches students: start with

observations of the client walking both forward

and backward, sitting, climbing stairs and doing

other functional tasks. Overall, Schneider says he

assesses stiffness vs. fluidity in the movement of

each body segment; these are issues with many

health problems. The key is isolation, or

independent movement of each body segment.

"In the extreme case," he says, "paralyzed people

have a concept of 'legs' that needs to be

differentiated; they've forgotten that their legs

can move separately from each other. Without

isolation, you have stiffness.

"Often, with back problems like Mark's,"

Schneider says, "the way one has used the legs

throughout life creates lower back damage.

Mark's knees never fully extend as he walks. He

pushes himself from the upper backㅡ there is

too much forward lean. At the time, he held his

head forward and his shoulders forward and up;

this has improved. Bicycling fit right into this

dynamic posture and aggravated it. Mark's back

is poorly organized, with extreme stiffness in the

thoracic paraspinals and weakness,

comparatively, above and below.

⇧Thoracic Paraspinal Muscle Location and Trigger Points

The Thoracic Paraspinal muscles run lengthwise, parallel to the spine. There are actually two layers of muscle that lie one on top of the other. Because these muscles attach to the vertebrae, or bones of the spine, they can cause problems with spinal misalignment and damage to the intervertebral discs.

The pain of Trigger Points in the Thoracic Paraspinal muscles often feels like it originates in the spine itself. The muscles feel hard and rigid, causing stiffness and decreased movement. It often feels as though the entire back is in spasm, which should respond to treatment with heat and superficial massage. When these treatments do not decrease the pain and spasm, Trigger Points are more likely the cause. Extreme tension in these muscles can lead to scoliosis, or a curvature of the spine.

Due to the close proximity of these muscles with the spine and nerves, Trigger Points in these muscles can also refer pain that mimics problems with organs of the chest and abdomen, such as appendicitis, kidney stones, angina, and lung problems.

Thoracic Paraspinal Stretch ⇧

1. Sit in a chair to stabilize hips.

2. Cross arms at mid forearm, and slowly roll forward, until a stretch is felt

3. Hold for 10-15 seconds.

4. Repeat three times, at least three times daily.

"His face and neck hold a lot of unresolved

emotionㅡjaw locked, sternodeidmastoids and

anterior neck generally very tight. His

abdominals are also extremely stiff. His stiff

areas-anterior neck, anterior and posterior chest,

and abdominal dominate his every movement.

"Mark is strong, fast and capableㅡhe's spent

years weightlifting and wrestling. Unfortunately,

being beefed up makes it harder to clear up

movement imbalances; you've invested that

much more in bad movement patterns.

''With movement imbalances, muscles ate

working in packs-big, insensate blocks, where a

group of proximal muscles tense up to 'help'

inappropriately with the work of a distal muscle.

You may see a psoas / pectorals /

stemocleidomastoid/scalene block like Mark's.

Or your client may have a gluteal/hamstring/

paraspinal/shoulder block, coupled with weak

neck and face, a pattern often seen in near-

sightedness. Or you may see an arched lower

back, protruding chest, with overworked upper

trapezius, lower pectorals, rhomboids and

paraspinals; this pattern goes with farsightedness.

Massage therapists need to carefully identify the

client's whole block."

Shortly after the dynamic posture evaluation,

Schneider's massage begins; it is a major

evaluative tool. "I observe the client's breathing

habits, generally and specifically.

People breathe into an area that is being

massaged; areas where this is delayed are

problematic. Mark's breathing was very

shallow, in the chest mostly, with effortful

exhalations. He didn't breathe at all into the

back. And there were, as I expected, arthritic

and fused joints in the lumbar area.

"I saw that Mark's problems started a long time

before he ever had symptoms. Too many people

look at the end resultㅡthe herniated disk in

Mark's case-of a lifelong movement problem as

if this symptom were the real problem you have

to solve, but it's not. Mark learned early on that

he has to fight for survival; it's in every move he

makes (Mark is a survivor of childhood physical

abuse). The problem may have started with

psychological armoring. It wasn't the job-related

jumping that hurt his back: it was the stiffness in

his jumping. As his pain developed, Mark may

have physiologically splinted against it

(tightened up muscles to shore up an area the

body perceives as weak or threatened),

intensifying his muscle spasms or adding more.

To heal himself, Mark was going to have to

change his movement patterns, and this was

going to create changes at every level of his being."

Physical therapy sees essentially two kinds of

muscle imbalances involved in lower back pain

ㅡtoo much lumbar curve (hyperlordotic) or too

little (flat lower back). They may apply the

classic testㅡhave the patient stand against a

wall and see how many hands' widths he or she

can fit into the lumbar curve-one is normal,

zero or two are problematic. The patient is

then asked to do a standing forward bend and

backbend and describe how each changes the

pain. If it lessens or radiates less, this is the

therapeutic direction for movementㅡpain in the

flat lower back is relieved by backbending; in the

hyperiordotic lower back, by forward bending.

Two leaders in the rehabilitation of backs have

lent their names to these diagnoses/regimen the

Williams protocol is predominantly a spinal

flexion program for hyperlordotic backs; the

MacKenzie, spinal extension for flat low backs.

Schneider says this is useful, as fir as it goes.

Carol Gallup thinks the Williams MacKenzie

distinction is often under-emphasized in the

holistic health community. "A few years ago,

during physical therapy school, I worked briefly

with a young woman with serious lower back

pain, radiating down the legs, with movement

and sensory losses in the legs. Kendra's back

pain began after she allowed a friend who

happened to be a holistic health practitioner to

work with her for a few months to 'correct' her

posture; before that she had had no problem.

This practitioner believed, on the basis of his

training, that the normal lumbar curve was

unhealthy, and that every lower back should be

flat. He did indeed flatten out her lumbar curve

ㅡand created a serious back problem for his

client.

"I see two morals in this story-first, the old

saying, 'if it ain't broke, don't fix it.' Second,

listen to the bioengineers and biomechanics.

They're telling us that the incredible ability of

the back to withstand the stresses we subject it

to every day is caused in part by its shape-

essentially, it's a spring, with the resiliency of a

spring, and it needs the normal amount of

kyphosis* in the upper back and the normal

amount of lordosis in the lower back.

[*Kyphosis (from Greek κυφός kyphos, a hump) is an abnormally excessive convex kyphotic curvature of the spine as it occurs in the cervical, thoracic and sacral regions. (Abnormal inward concave lordotic curving of the cervical and lumbar regions of the spine is called lordosis.)

Hunchback / Kyphosis⇧]

*

⇧ *Lordosis is defined as an excessive inward curve of the spine. It differs from the spine's normal curves at the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar regions, which are, to a degree, either kyphotic (near the neck) or lordotic (closer to the low back).]

So when I met Kendra she had a 'MacKenzie'

back. I gave Kendra some standing and other

[types of] backbends, and her pain immediately

started to lessen and centralize (radiate less), a

sure sign that backbending was an important

direction to take with her therapy.

"I myself happen to tend in the opposite

direction, hyperlordoticㅡa 'Williams' back. I've

found that I do best if, for every six or eight

spinal flexion exercises, I do two or three spinal

extensions. Bear in mind also that serious lower

back pain can occur gram for clients with spine,

joint and when the lower back curve is normal

ㅡthe client may still have muscle tightness,

muscle spasm, very limited mobility."

With the Williams protocol, physical therapists tend to automatically add exercises to strengthen

the abdominals. We know someone who had such severe back pain

that he was admitted to the hospital; a physical therapist looked at his chart and said, "You'll have to strengthen those abdominals; you've got a muscle imbalance causing all that pain." To prove her point, she casually poked at his abdomenㅡand then looked shocked. The patient was a rugby player with magnificent abdominals. He was indeed hyperlordotic, but those strong abdominals weren't correcting it.

Why not? Schneider feels that the problem in

unbalanced movement patterns lies with the

nervous system predominantly and the muscles

only secondarily. Thus, strengthening the

underused muscles alone or in conjunction with

spinal flexion or extension exercises will not

correct the problem. "The brain ignores muscles

in areas it regards as unsupported," he explains.

"'Support' is good mobility in the muscles, not

brute strength; Mark, for example, is very strong

but stiff in the thoracic back, and his brain registers

this as nonsupport and tends to ignore muscles

above it." Schneider's view is at odds with that of

chiropractors and physical therapists, who routinely

make use of lumbar belts, believing they support

the lower back by immobilizing it.

"Hyperflexibility is also seen by the brain as nonsupport-if your client is pathologically loose-jointed, congenitally or from bad stretching programs, there's compensatory muscle tightness."

We need to interfere with the neural habit of

overusing some muscle groups, as if they are the

only muscles it is natural to work, and ignoring

others. A good program for clients with spine,

joint and many other problems involves serious reprogramming. Most of us have immobile toes, for example, from walking in shoes on cement sidewalks, so that our toes and feet didn't develop a pattern of pleasurable sensorimotor interaction with the ground; we can create such a pattern by walking and running on a beach or grassy surface. This is importantㅡstiff feet and calves contribute stiffness to every other joint in the body. And we can interfere with other rigidities in our walk by walking and running backwards. Coordination exercises are very helpful. We can explore the full range of motion of our joints, with movements that take us through many planes (we tend to live in the sagittal, or forward/backward, plane). Massage is essential, since it breaks adhesions and creates new sensory input to the brain, sending it the message that muscles can be soft and mobile. And it is essential for clearing up muscle spasms. Rolling on the floor or the ground is especially helpful, recruiting side muscles that are usually ignored.

We've used the general terms "stiffness", "fluidity,"

and "immobility" purposely when talking about

evaluating movement; these are fairly easy

distinctions to make, visually and through touch.

Later, the evaluator can note muscle spasms or

limited range of motion at the joint. Schneider

found limited joint mobility in Donegan's lumbar

spine and habitual muscle spasm in his psoas,

pectorals, serratus anterior, intercostals, scalenes

and sternocleidomastoid.

"More natural ways of moving-muscles doing only their own work, not adding unnecessary effort, what we call isolationㅡcan't fully take hold until habitual muscle spasm is gone. And it goes away slowly, very slowly, over time. You can clear it up in the sessionㅡwith Self-Healing Neurological Massage (a light-pressure, very vigorous vibrating touch that is a cross between brisk shaking of the muscle and tapotement), tapotement, deep tissue massage, breathing exercisesㅡand the client

walks out much looser, feeling great, thinking

you're wonderful. But the dynamic posture and

the lack of awareness that put it there didn't go away. The client will go home and torque or overload or suddenly strain the back, and the pain may return in full force, and unless you've educated them about the process, they may think the session was a failure. You need to loosen them up and get them doing the movement exercises that teach the brain how to isolate, how to move naturally. There's a long transition period with ups and downs as the new adaptations start, and then eventually they're complete and the spasm is gone."

Donegan was already on a one-hour daily exercise regimen of exercycle workouts, standing lateral and forward bends, knee bends, and stretches for the groin, hamstrings, and calvesㅡ"the standard ones for back pain, on printed sheets that you get from the physical therapist and the chiropractor," Donegan recalls. "They were teaching me movements, trying to figure out bow to get my legs going again, and it wasn't helping. Meir taught me how to move. He pointed out places I was

holding myself; I had an immediate knowledge

that the movements he gave me would release

that area and that release there was the key.

Every exercise improved a symptom."

The regimen that Schneider gave Donegan is described below because it is helpful with his pattern of stiffness and muscle tension, and above all, because it is helping him develop kinesthetic awareness so that he can sense for himself the movements that his body needs. No one program is universally helpful; this one should be looked at in the light of the principles we have discussed.

Exercises to reprogram for soft, fluid movement

The exercises need to be repeated many times; the

effect on the nervous system is slow and

cumulative. All rotations should be done in both

directions.

Seated: First, rotate the navel in the transverse

(horizontal) plane, in one direction and then the

other; then, starting at the base of the spine, do a

vertebra-by-vertebra version of these horizontal

rotations, moving the axis of rotation up one

vertebra at a time. Still in the chair, rotate the

head in both directions.

Spinal flexion and extension can be performed

standing or sitting. On his own, the client will find

it easier to do spinal extension exercises in the

prone position, raising the upper and lower body

separately, then simultaneously, actively (bow or

locust movements) or passively (extending the

arms to passively extend the upper spine). Check

whether the client is a MacKenzie or Williams

type, and let flexion or extension prodominate

accordingly. (Some people with back problems

have normal lordosis; give them equal amounts.)

To create kinesthetic awareness, perform these

exercises very slowly, feeling each vertebra.

On the floor: Roll from side to side on the floor.

On hands and knees, divide the back into four

segmentsㅡlower, waist, middle and upperㅡand

separately raise and lower each segment

repeatedly. (In Mark's first session, this was

followed by massage in the prone position, with

the knees drawn under the abdomen.) In the

supine position, knees bent and apart, soles

touching, groin as open as possible, bring each

knee alternately all the way over to the opposite

side and back again. Hold the breath on the inhale,

raise and lower the abdomen 10 times, then hold

the breath on the exhale and do the same thing.

Next, as you inhale, picture yourself filling with

air like a pitcher filling with water all the way up

to the top of the chest; picture the air pouring out

as you exhale. Make circles with the fingers, then

the wrist, then the forearm, tapping on muscles

(especially flexors) proximal to the joint with the

other hand, to dampen the involvement of

unnecessarily recruited muscles. Rotate the shoulder.

Standing, kick each leg sideways. Stand on a stair

or step, let one leg hang down and rotate it in both

directions. With your back to the stairs, lift each

leg alternately to the lowest stair. Then walk

backward.

Massage therapist Ferrell was advised to follow

up with deep tissue massage to the entire thoracic

area and gentle effleurage*, tapotement and

vibration to the lower and upper back.

* Effleurage as (noun) 1.a form of massage

involving a repeated circular stroking movement

made with the palm of the hand. (verb) 1.massage

with a circular stroking movement."effleurage the

shoulders and press gently"

Donegan practiced the exercises for two

hours a day; as his endurance increased, he

went up to four hours a day and then six.

He enrolled in the School for Self-Healing

and is now an advanced student. Recently

he had surgery to remove the bolts and braces from his back. When he recovered consciousness after the surgery, he began getting massage and doing movement exercisesㅡhead and neck rotationsㅡin the hospital bed. "The massage was a stronger painkiller than three pain pills, and lasted longer," he said. Two and a half weeks later, the swelling had disappeared and he could ride his beloved bike again.

"Now I feel that I've created enough

looseness and awareness in my body so I

know the next stepㅡhow to respect my

pain, not move it, stay in my good range ㅡthen

move it, move through it, soften it,

move more fluidly" he said. "The worst

thing about the pain was haw it isofated

me socially. These days, I can visit my

friends, go there on my bike, hang out,

without having to get up and leave because

the pain is too bad. I have a full social life

and I'm building a massage and movement

business in Ukiah. I feel like in two years

I'll have fully recovered."

Meir Schneider, Ph.D., L.M. T, an internationany

known therapist and educator, is

the creator of the Meir Schneider Self-Healing

Method the author of two books,

Self-Healing My Lie and Vision andThe

Handbook of Self-Healing, and the

founder/director of the Center and School for

Self-Healing in San Francisco. As a teenager,

he overcome blindness caused by congenital

cataracts and other serious vision problems and

today has an unrestricted driver's license.

Carol Gadup is an advanced student of

Self-Healing, Registrar of the School for Self-

Healing, staff writer of the Self-Healing

Research Foundation, and the author of

numerous magazine articles. She studied

physical therapy at the Mayo Clinic and is

now a master's degree candidate in research

psychology at San Francisco State University .

1.⇧On hand and knees, Donegan raises and low the upper back.

Source: http://self-healing.org/wp-content/uploads/2009/01/1moving-out-of-back-problems.pdf

says, "I'm fidgety because of pain; my body's

telling me to move, so I do it everywhere on the

bus, sitting around with friends,wherever I am."

Donegan, 36, is recovering from a very painful

back problem that nearly crippled him, a

herniated inter-vertebral disk in the lumbar

spine. He weaned himself off heavy medications

offered by physicians and chose instead to heal

himself through natural movement, the key

element in self-healing.

Moving in a natural way frees you. It is well-

known in movement science that the skilled

performer has more degrees of freedom

(movement choices) than the novice. When you

look at a film of Fred Astaire and Ginger

Rogers dancing, you feel their looseness, ease

and pleasure in movement. It says a lot about

our culture that they had to work hard to make

it second nature to move easily. As they dance,

you see that their muscles work only as hard as

appropriate and don't substitute for the work of

other muscles (the principle of isolation).

Without tensing up the abdominals, they move

loosely from their center (the navel area). It's

much less effortful, energy-costly and wearing

than the "normal" movement patterns most of us

exhibit, which eventually create chronic health

problems.

Athletes and dancers don't necessarily move

naturally; when they use the body as a tool, they

block out a sense of its problems and needs.

Natural movement comes out of kinesthetic

awareness, a deep, subtle sense of movement-of

breath, energy, blood and other fluids throughout

the body, of joints finding their full range in all

planes, of muscles becoming supple, strong and

balanced. You become aware of the body's

specific need for movement at any given time.

Natural movement healsㅡit increases circulation,

reduces inflammation, creates strength,

endurance and a sense of well-being, and

nurtures every part of the body, including the

joints. Helping the client restore natural

movement is essential in working with joint and

spine problems.

Unfortunately, most people move in an

unbalanced, constricted way. This kind of

movementㅡpatterns of overuse, under-use and

misuseㅡis damaging to the joints, including

those of the spine. Doing more of it in the name

of "exercise" will only make you worse.

We suggest reviewing the article, "Movement is

Life," (Issue #60, March/April 1996); those

exercises and principles are helpful for people

with back problems.

A back problem years in the making

When Donegan was 29, his job required him to

climb up and jump down to fetch items from

grocery stockrooms many times a day. "We were

expected to move fast," he said. He woke up one

morning feeling that his left leg didn't want to

move. A chiropractor diagnosed herniated disk

(also known as disk prolapse or slipped disk), a

complication of degenerative disk disease. Like

cartilage, intervertebral disks in the spinal

column are believed by physicians to degenerate

inevitably, beginning at early adulthood. As a

complication, the disk may herniate or rupture. A

strong ligament keeps it from bulging directly

backward, so it moves posterolaterally, where it

may compress or stretch a spinal nerve root.

Posterolateral: situated on the side and towards

the back of the body. The result is radiating pain,

muscle weakness and sensory losses, always

along the distribution of the spinal nerve. This is

actually one form of sciatica, which can also

begin with compression further down the nerve.

Most prevalent in young men, herniated disk is

rare after middle age, because the disk has lost a

lot of its mass.

Four months of chiropractic treatment only

aggravated the problem. Donegan tried physical

therapy, and it worsened again, until muscle

spasm and pain prevented movement in the leg

altogether.

Two surgeries brought only temporary respite.

In the first operation, part of the disk and of the

bony arch around the spinal cord were trimmed

away; in the second, more of the disk was

removed and two vertebrae were fused together.

After the second surgery, new symptoms came

onㅡnumbness in the left leg, high blood pressure

, irregular heart rate, bowel and bladder

problems. The right leg had been the anchor for

crutch walking; now he lost sensation and

movement in it, too.

"I was looking at a wheelchair next," Donegan

said. "I was depressedㅡmy whole world was

falling apart. The pain gave me nausea and

vomiting. Let me tell you about extreme pain.

You can take it for a day and it's okay. Two days,

and you start getting tired of it, but on the third

day, you don't have anything left. You're not you

anymore."

Another surgeon told Donegan he could remove

the rest of the damaged disk and stabilize the

region with bone transplants and internal braces

and screws. There would be a new source of pain,

however, from the braces. The surgery restored

his ability to walk but left his back swollen and

painful, and "I had nothing left, no will,"Donegan

said. At a pain clinic in Mendocino, California,

Donegan began working with massage therapist

Audrey Ferrell, who practices neuromuscular

therapy. Ferrell gave him massage and movement

exercises. Gradually his pain abated enough that

he could resume his favorite activity, bicycling.

''I gave the doctor back all of his prescription

pain medications; the only thing I kept was over-

the-counter ibuprofen." A year later, Ferrell

brought him to Meir Schneider. " Meir glanced at

me and told me where my pain was," Donegan

recalls.

While Schneider's evaluation seemed fast and

effortless to Donegan, he used, as always, the

method he teaches students: start with

observations of the client walking both forward

and backward, sitting, climbing stairs and doing

other functional tasks. Overall, Schneider says he

assesses stiffness vs. fluidity in the movement of

each body segment; these are issues with many

health problems. The key is isolation, or

independent movement of each body segment.

"In the extreme case," he says, "paralyzed people

have a concept of 'legs' that needs to be

differentiated; they've forgotten that their legs

can move separately from each other. Without

isolation, you have stiffness.

"Often, with back problems like Mark's,"

Schneider says, "the way one has used the legs

throughout life creates lower back damage.

Mark's knees never fully extend as he walks. He

pushes himself from the upper backㅡ there is

too much forward lean. At the time, he held his

head forward and his shoulders forward and up;

this has improved. Bicycling fit right into this

dynamic posture and aggravated it. Mark's back

is poorly organized, with extreme stiffness in the

thoracic paraspinals and weakness,

comparatively, above and below.

⇧Thoracic Paraspinal Muscle Location and Trigger Points

The Thoracic Paraspinal muscles run lengthwise, parallel to the spine. There are actually two layers of muscle that lie one on top of the other. Because these muscles attach to the vertebrae, or bones of the spine, they can cause problems with spinal misalignment and damage to the intervertebral discs.

The pain of Trigger Points in the Thoracic Paraspinal muscles often feels like it originates in the spine itself. The muscles feel hard and rigid, causing stiffness and decreased movement. It often feels as though the entire back is in spasm, which should respond to treatment with heat and superficial massage. When these treatments do not decrease the pain and spasm, Trigger Points are more likely the cause. Extreme tension in these muscles can lead to scoliosis, or a curvature of the spine.

Due to the close proximity of these muscles with the spine and nerves, Trigger Points in these muscles can also refer pain that mimics problems with organs of the chest and abdomen, such as appendicitis, kidney stones, angina, and lung problems.

Thoracic Paraspinal Stretch ⇧

1. Sit in a chair to stabilize hips.

2. Cross arms at mid forearm, and slowly roll forward, until a stretch is felt

3. Hold for 10-15 seconds.

4. Repeat three times, at least three times daily.

"His face and neck hold a lot of unresolved

emotionㅡjaw locked, sternodeidmastoids and

anterior neck generally very tight. His

abdominals are also extremely stiff. His stiff

areas-anterior neck, anterior and posterior chest,

and abdominal dominate his every movement.

"Mark is strong, fast and capableㅡhe's spent

years weightlifting and wrestling. Unfortunately,

being beefed up makes it harder to clear up

movement imbalances; you've invested that

much more in bad movement patterns.

''With movement imbalances, muscles ate

working in packs-big, insensate blocks, where a

group of proximal muscles tense up to 'help'

inappropriately with the work of a distal muscle.

You may see a psoas / pectorals /

stemocleidomastoid/scalene block like Mark's.

Or your client may have a gluteal/hamstring/

paraspinal/shoulder block, coupled with weak

neck and face, a pattern often seen in near-

sightedness. Or you may see an arched lower

back, protruding chest, with overworked upper

trapezius, lower pectorals, rhomboids and

paraspinals; this pattern goes with farsightedness.

Massage therapists need to carefully identify the

client's whole block."

Shortly after the dynamic posture evaluation,

Schneider's massage begins; it is a major

evaluative tool. "I observe the client's breathing

habits, generally and specifically.

People breathe into an area that is being

massaged; areas where this is delayed are

problematic. Mark's breathing was very

shallow, in the chest mostly, with effortful

exhalations. He didn't breathe at all into the

back. And there were, as I expected, arthritic

and fused joints in the lumbar area.

"I saw that Mark's problems started a long time

before he ever had symptoms. Too many people

look at the end resultㅡthe herniated disk in

Mark's case-of a lifelong movement problem as

if this symptom were the real problem you have

to solve, but it's not. Mark learned early on that

he has to fight for survival; it's in every move he

makes (Mark is a survivor of childhood physical

abuse). The problem may have started with

psychological armoring. It wasn't the job-related

jumping that hurt his back: it was the stiffness in

his jumping. As his pain developed, Mark may

have physiologically splinted against it

(tightened up muscles to shore up an area the

body perceives as weak or threatened),

intensifying his muscle spasms or adding more.

To heal himself, Mark was going to have to

change his movement patterns, and this was

going to create changes at every level of his being."

Physical therapy sees essentially two kinds of

muscle imbalances involved in lower back pain

ㅡtoo much lumbar curve (hyperlordotic) or too

little (flat lower back). They may apply the

classic testㅡhave the patient stand against a

wall and see how many hands' widths he or she

can fit into the lumbar curve-one is normal,

zero or two are problematic. The patient is

then asked to do a standing forward bend and

backbend and describe how each changes the

pain. If it lessens or radiates less, this is the

therapeutic direction for movementㅡpain in the

flat lower back is relieved by backbending; in the

hyperiordotic lower back, by forward bending.

Two leaders in the rehabilitation of backs have

lent their names to these diagnoses/regimen the

Williams protocol is predominantly a spinal

flexion program for hyperlordotic backs; the

MacKenzie, spinal extension for flat low backs.

Schneider says this is useful, as fir as it goes.

Carol Gallup thinks the Williams MacKenzie

distinction is often under-emphasized in the

holistic health community. "A few years ago,

during physical therapy school, I worked briefly

with a young woman with serious lower back

pain, radiating down the legs, with movement

and sensory losses in the legs. Kendra's back

pain began after she allowed a friend who

happened to be a holistic health practitioner to

work with her for a few months to 'correct' her

posture; before that she had had no problem.

This practitioner believed, on the basis of his

training, that the normal lumbar curve was

unhealthy, and that every lower back should be

flat. He did indeed flatten out her lumbar curve

ㅡand created a serious back problem for his

client.

"I see two morals in this story-first, the old

saying, 'if it ain't broke, don't fix it.' Second,

listen to the bioengineers and biomechanics.

They're telling us that the incredible ability of

the back to withstand the stresses we subject it

to every day is caused in part by its shape-

essentially, it's a spring, with the resiliency of a

spring, and it needs the normal amount of

kyphosis* in the upper back and the normal

amount of lordosis in the lower back.

[*Kyphosis (from Greek κυφός kyphos, a hump) is an abnormally excessive convex kyphotic curvature of the spine as it occurs in the cervical, thoracic and sacral regions. (Abnormal inward concave lordotic curving of the cervical and lumbar regions of the spine is called lordosis.)

Hunchback / Kyphosis⇧]

*

⇧ *Lordosis is defined as an excessive inward curve of the spine. It differs from the spine's normal curves at the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar regions, which are, to a degree, either kyphotic (near the neck) or lordotic (closer to the low back).]

So when I met Kendra she had a 'MacKenzie'

back. I gave Kendra some standing and other

[types of] backbends, and her pain immediately

started to lessen and centralize (radiate less), a

sure sign that backbending was an important

direction to take with her therapy.

"I myself happen to tend in the opposite

direction, hyperlordoticㅡa 'Williams' back. I've

found that I do best if, for every six or eight

spinal flexion exercises, I do two or three spinal

extensions. Bear in mind also that serious lower

back pain can occur gram for clients with spine,

joint and when the lower back curve is normal

ㅡthe client may still have muscle tightness,

muscle spasm, very limited mobility."

With the Williams protocol, physical therapists tend to automatically add exercises to strengthen

the abdominals. We know someone who had such severe back pain

that he was admitted to the hospital; a physical therapist looked at his chart and said, "You'll have to strengthen those abdominals; you've got a muscle imbalance causing all that pain." To prove her point, she casually poked at his abdomenㅡand then looked shocked. The patient was a rugby player with magnificent abdominals. He was indeed hyperlordotic, but those strong abdominals weren't correcting it.

Why not? Schneider feels that the problem in

unbalanced movement patterns lies with the

nervous system predominantly and the muscles

only secondarily. Thus, strengthening the

underused muscles alone or in conjunction with

spinal flexion or extension exercises will not

correct the problem. "The brain ignores muscles

in areas it regards as unsupported," he explains.

"'Support' is good mobility in the muscles, not

brute strength; Mark, for example, is very strong

but stiff in the thoracic back, and his brain registers

this as nonsupport and tends to ignore muscles

above it." Schneider's view is at odds with that of

chiropractors and physical therapists, who routinely

make use of lumbar belts, believing they support

the lower back by immobilizing it.

"Hyperflexibility is also seen by the brain as nonsupport-if your client is pathologically loose-jointed, congenitally or from bad stretching programs, there's compensatory muscle tightness."

We need to interfere with the neural habit of

overusing some muscle groups, as if they are the

only muscles it is natural to work, and ignoring

others. A good program for clients with spine,

joint and many other problems involves serious reprogramming. Most of us have immobile toes, for example, from walking in shoes on cement sidewalks, so that our toes and feet didn't develop a pattern of pleasurable sensorimotor interaction with the ground; we can create such a pattern by walking and running on a beach or grassy surface. This is importantㅡstiff feet and calves contribute stiffness to every other joint in the body. And we can interfere with other rigidities in our walk by walking and running backwards. Coordination exercises are very helpful. We can explore the full range of motion of our joints, with movements that take us through many planes (we tend to live in the sagittal, or forward/backward, plane). Massage is essential, since it breaks adhesions and creates new sensory input to the brain, sending it the message that muscles can be soft and mobile. And it is essential for clearing up muscle spasms. Rolling on the floor or the ground is especially helpful, recruiting side muscles that are usually ignored.

We've used the general terms "stiffness", "fluidity,"

and "immobility" purposely when talking about

evaluating movement; these are fairly easy

distinctions to make, visually and through touch.

Later, the evaluator can note muscle spasms or

limited range of motion at the joint. Schneider

found limited joint mobility in Donegan's lumbar

spine and habitual muscle spasm in his psoas,

pectorals, serratus anterior, intercostals, scalenes

and sternocleidomastoid.

"More natural ways of moving-muscles doing only their own work, not adding unnecessary effort, what we call isolationㅡcan't fully take hold until habitual muscle spasm is gone. And it goes away slowly, very slowly, over time. You can clear it up in the sessionㅡwith Self-Healing Neurological Massage (a light-pressure, very vigorous vibrating touch that is a cross between brisk shaking of the muscle and tapotement), tapotement, deep tissue massage, breathing exercisesㅡand the client

walks out much looser, feeling great, thinking

you're wonderful. But the dynamic posture and

the lack of awareness that put it there didn't go away. The client will go home and torque or overload or suddenly strain the back, and the pain may return in full force, and unless you've educated them about the process, they may think the session was a failure. You need to loosen them up and get them doing the movement exercises that teach the brain how to isolate, how to move naturally. There's a long transition period with ups and downs as the new adaptations start, and then eventually they're complete and the spasm is gone."

Donegan was already on a one-hour daily exercise regimen of exercycle workouts, standing lateral and forward bends, knee bends, and stretches for the groin, hamstrings, and calvesㅡ"the standard ones for back pain, on printed sheets that you get from the physical therapist and the chiropractor," Donegan recalls. "They were teaching me movements, trying to figure out bow to get my legs going again, and it wasn't helping. Meir taught me how to move. He pointed out places I was

holding myself; I had an immediate knowledge

that the movements he gave me would release

that area and that release there was the key.

Every exercise improved a symptom."

The regimen that Schneider gave Donegan is described below because it is helpful with his pattern of stiffness and muscle tension, and above all, because it is helping him develop kinesthetic awareness so that he can sense for himself the movements that his body needs. No one program is universally helpful; this one should be looked at in the light of the principles we have discussed.

Exercises to reprogram for soft, fluid movement

The exercises need to be repeated many times; the

effect on the nervous system is slow and

cumulative. All rotations should be done in both

directions.

Seated: First, rotate the navel in the transverse

(horizontal) plane, in one direction and then the

other; then, starting at the base of the spine, do a

vertebra-by-vertebra version of these horizontal

rotations, moving the axis of rotation up one

vertebra at a time. Still in the chair, rotate the

head in both directions.

Spinal flexion and extension can be performed

standing or sitting. On his own, the client will find

it easier to do spinal extension exercises in the

prone position, raising the upper and lower body

separately, then simultaneously, actively (bow or

locust movements) or passively (extending the

arms to passively extend the upper spine). Check

whether the client is a MacKenzie or Williams

type, and let flexion or extension prodominate

accordingly. (Some people with back problems

have normal lordosis; give them equal amounts.)

To create kinesthetic awareness, perform these

exercises very slowly, feeling each vertebra.

On the floor: Roll from side to side on the floor.

On hands and knees, divide the back into four

segmentsㅡlower, waist, middle and upperㅡand

separately raise and lower each segment

repeatedly. (In Mark's first session, this was

followed by massage in the prone position, with

the knees drawn under the abdomen.) In the

supine position, knees bent and apart, soles

touching, groin as open as possible, bring each

knee alternately all the way over to the opposite

side and back again. Hold the breath on the inhale,

raise and lower the abdomen 10 times, then hold

the breath on the exhale and do the same thing.

Next, as you inhale, picture yourself filling with

air like a pitcher filling with water all the way up

to the top of the chest; picture the air pouring out

as you exhale. Make circles with the fingers, then

the wrist, then the forearm, tapping on muscles

(especially flexors) proximal to the joint with the

other hand, to dampen the involvement of

unnecessarily recruited muscles. Rotate the shoulder.

Standing, kick each leg sideways. Stand on a stair

or step, let one leg hang down and rotate it in both

directions. With your back to the stairs, lift each

leg alternately to the lowest stair. Then walk

backward.

Massage therapist Ferrell was advised to follow

up with deep tissue massage to the entire thoracic

area and gentle effleurage*, tapotement and

vibration to the lower and upper back.

* Effleurage as (noun) 1.a form of massage

involving a repeated circular stroking movement

made with the palm of the hand. (verb) 1.massage

with a circular stroking movement."effleurage the

shoulders and press gently"

Donegan practiced the exercises for two

hours a day; as his endurance increased, he

went up to four hours a day and then six.

He enrolled in the School for Self-Healing

and is now an advanced student. Recently

he had surgery to remove the bolts and braces from his back. When he recovered consciousness after the surgery, he began getting massage and doing movement exercisesㅡhead and neck rotationsㅡin the hospital bed. "The massage was a stronger painkiller than three pain pills, and lasted longer," he said. Two and a half weeks later, the swelling had disappeared and he could ride his beloved bike again.

"Now I feel that I've created enough

looseness and awareness in my body so I

know the next stepㅡhow to respect my

pain, not move it, stay in my good range ㅡthen

move it, move through it, soften it,

move more fluidly" he said. "The worst

thing about the pain was haw it isofated

me socially. These days, I can visit my

friends, go there on my bike, hang out,

without having to get up and leave because

the pain is too bad. I have a full social life

and I'm building a massage and movement

business in Ukiah. I feel like in two years

I'll have fully recovered."

Meir Schneider, Ph.D., L.M. T, an internationany

known therapist and educator, is

the creator of the Meir Schneider Self-Healing

Method the author of two books,

Self-Healing My Lie and Vision andThe

Handbook of Self-Healing, and the

founder/director of the Center and School for

Self-Healing in San Francisco. As a teenager,

he overcome blindness caused by congenital

cataracts and other serious vision problems and

today has an unrestricted driver's license.

Carol Gadup is an advanced student of

Self-Healing, Registrar of the School for Self-

Healing, staff writer of the Self-Healing

Research Foundation, and the author of

numerous magazine articles. She studied

physical therapy at the Mayo Clinic and is

now a master's degree candidate in research

psychology at San Francisco State University .

1.⇧On hand and knees, Donegan raises and low the upper back.

Source: http://self-healing.org/wp-content/uploads/2009/01/1moving-out-of-back-problems.pdf

No comments:

Post a Comment