Ex-footballer recounts Japanese

Occupation, being screened for

execution and 1948 Olympics

Mr Chia's ability to skirt danger on

the field was honed as a teenager

growing up in war-torn Singapore.

SINGAPORE - In his footballing

heyday, Mr Chia Boon Leong was

known as "twinkletoes" for the way

he danced around opponents with

ease.

That ability to skirt danger was

honed as a teenager growing up in

war-torn Singapore, where

he continued to play football, often in

Jalan Besar Stadium and at a field

behind the Singapore General

Hospital, near his family home in

Tiong Bahru.

He was a founding member of Pasir

Panjang Rovers - having grown up

in the area - a cosmopolitan team that

played only friendly matches before

the war as multi-ethnic teams were

not allowed in the Singapore

Amateur Football Association's

leagues.

In about six short years, he went

from being screened as part of

efforts to weed out anti-Japanese

elements - which meant execution

for some - to being selected as one

of two Singaporeans to represent

China in football in London at the

1948 Olympics.

It was an achievement not without

hardship, the 97-year-old told as he

recalled his growing up years.

Ex-footballer

recounts

Japanese

Occupation,

being screened

for execution

and 1948

Olympics

SINGAPORE - In his football-

ing heyday, Mr Chia Boon

Leong was known as

"twinkletoes" for the way he

danced around opponents

with ease.

That ability to skirt danger

was honed as a teenager

growing up in war-torn

Singapore, where he

continued to play football,

often in Jalan Besar Stadium

and at a field behind the

Singapore General Hospital,

near his family home

in Tiong Bahru.

He was a founding member

of Pasir Panjang Rovers -

having grown up in the area -

a cosmopolitan team that

played only friendly matches

before the war as multi-ethnic

teams were not allowed in the

Singapore Amateur Football

Association's leagues.

In about six short years, he

went from being screened as

part of efforts to weed out

anti-Japanese elements -

which meant execution for

some - to being selected as one

of two Singaporeans to

represent China in football in

London at the 1948 Olympics.

It was an achievement not

without hardship, the 97-year-

old told as he recalled his

growing up years.

It was on Dec 8, 1941, at

around 5am, that the realities

of war first hit home for Mr

Chia, who was born on New

Year's Day, 1925.

"All of a sudden, one my

neighbours came to my

house and shouted loudly

'Japanese bombing Singapore

already'," said Mr Chia, who

was then living in Pasir

Panjang, near Yew Siang

Road.

"During the Occupation, as

far as I recall, I was not too

worried. I did not know

what was going on at that

age, so there was no reason

to be anxious," he said.

But in the weeks to come, Mr

Chia left his family home for

Tiong Bahru, where his

family felt they might be safer

from the coming invasion.

He remained there

throughout the Occupation.

While moving away from

Pasir Panjang meant they

escaped a fierce firefight -

the battle of Bukit Chandu

was fought not far away on

Feb 14, 1942 - Mr Chia's

family was still not far from

danger in Tiong Bahru.

Eng Hoon Street, located

about 130m away from

where his family lived in

Eng Watt Street, bore the

brunt of Japanese shelling

in the area, he said.

Within weeks of the British

surrender on Feb 15, 1942,

Mr Chia was told to report

to an inspection site where

Japanese soldiers screened

Chinese men and took away

those suspected of being

anti-Japanese for execution.

The Japanese military

operation, called Operation

Sook Ching, saw Chinese

males between the ages of

18 and 50 summoned to

mass screening centres all

over the island.

"Someone in Tiong Bahru

said to report to an open

area opposite the police

station at the intersection of

Keppel, Tanjong Pagar and

Cantonment roads, so I

went not knowing what

was happening," said Mr

Chia, who was 17 at that

point.

"As a schoolboy I just carried

on and followed instructions.

We lined up, one by one, to

face a Japanese soldier and

some were told to go to a

lorry, I did not know why

then.

"It was only some time later

that we were told those on

the lorries were taken some

where else to be executed."

Mr Chia said he later heard

that his half-brother, a

cousin, and a Pasir Panjang

Rovers coach were taken

away, and they were never

seen again.

He also recalled another

incident in Tiong Bahru Road:

Japanese officers made a

group of Chinese men line up

as an informant, who wore a

hood to hide his identity,

pointed out those who had

served under the British as

members of a voluntary

military reserve.

As the Occupation wore on

and people got more used

to living under Japanese

rule, Mr Chia enrolled in a

Japanese school in Queen

Street in late 1942.

In mid-1943, as an 18-year-

old, he worked for the

Japanese in a telegraphy

company, where he sent

and received messages in

morse code.

By that time, the Syonan

Sports Association was

formed, and Mr Chia

recalled going to Jalan Besar

Stadium to play football

every day after work.

Beyond organising sports

competitions,the association

was a vehicle that mobilised

auxiliary manpower to

assist with various tasks,

including clearing debris

and casualties when

bombings occurred.

As members of the

association, Mr Chia and his

Rovers teammates were

tapped to help with such

assignments, receiving

rations of rice and

cigarettes in exchange.

He said he enjoyed the

camaraderie he shared with

his teammates as they went

about performing menial

tasks, such as digging

trenches at the Padang and

planting tapioca in Holland

Road.

"But the most important

thing was that we got our

rations," he said. "I didn't

smoke so I sold my

cigarettes for extra money."

On the pitch, the Rovers

were a dominant force,

winning all their matches

between May to September

1943 to top the league.

But it was matches against

Malayan opposition that

Mr Chia remembers the

most fondly.

Dinners served when the

association hosted visiting

teams were of a higher

quality than everyday meals,

which often comprised

porridge and sweet potatoes.

Players rushed to get a share

of the food when it was

served.

At one dinner, a guest was

peeved by such behaviour,

and threw his dentures into

a bowl of soup as soon as it

was served so that no one

else would have it.

"What did we do? We all had

a good laugh," said Mr Chia.

On two occasions - in late

1943 and mid-1944 - Mr Chia

was part of a Syonan team

that made "goodwill" tours

to Malaya, where it played

against local teams.

Mr Chia recalled travelling

by lorry between Kuala

Lumpur and Ipoh on the

second tour. The team

feared attack by anti-

Japanese guerrilla fighters

targeting the Japanese

officer who accompanied

the team.

"Although it was not a

comfortable trip, somehow

the team still enjoyed

ourselves," he said.

Between the Japanese

surrender on Sept 2, 1945,

and the surrender ceremony

in Singapore on Sept 12,

Mr Chia said the Japanese

military remained in control

and people were still fearful

of them.

After hearing about the

Japanese surrender, Mr Chia

and his Rovers teammates

gathered in a home in

Lavender Street and

celebrated loudly as they

anticipated liberation from

Japanese rule, only to be

confronted by an armed

Japanese soldier.

"We were lucky because we

said we were celebrating a

birthday and he left us alone,"

said Mr Chia.

After the war ended, he

continued to play football,

including for the Lien Hwa

(United Chinese) team that

toured Asia in December

1947.

The next year, he was

selected to represent China

in the Olympics, despite

being Singapore-born.

The Chinese team would play

just one match at the Games,

losing to Turkey in the first

knock-out round.

But Mr Chia, who started for

the Chinese team, remains

the only Singaporean to

have taken the field in

football at the Olympics.

Two other footballers went

to the Olympics as part of

the Chinese team - Chua

Boon Lay in 1936 and Chu

Chee Seng in 1948 - but

never played.

It was on Dec 8, 1941, at around 5am, that the realities of war first hit home for Mr Chia, who was born on New Year's Day, 1925.

"All of a sudden, one my neighbours came to my house and shouted loudly 'Japanese bombing Singapore already'," said Mr Chia, who was then living in Pasir Panjang, near Yew Siang Road.

[ map here ]

The lane was named after his businessman father who died in 1930.

( more details here )

Pioneers: The philanthropist of Yew Siang Road

Our History

We hope you’re

having as much fun

as we are, learning

about the historical

figures behind the

names of roads in

the Pasir Panjang

area! Today we shall

find out more about

the pioneer named

for Yew Siang Road,

a residential side

road opposite Pasir

Panjang MRT station.

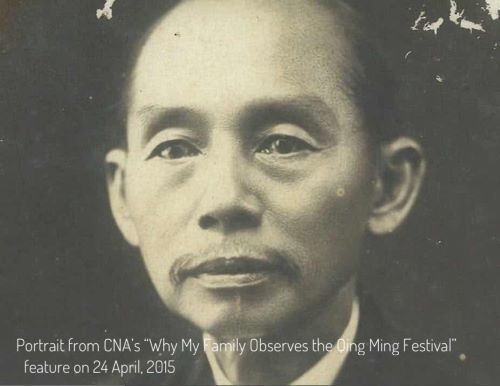

Chia Yew Siang (谢有

祥) (b. 1867, China–

death 8 May 1930,

Singapore) was a

merchant and

philanthropist. He

was the managing

proprietor of Chop

Hong Hoe at George

Street, and is

believed to have

traded in rubber and

spices.

A prominent member

of the Chinese

community in

Singapore, he was

part of the Singapore

Chinese Chamber of

Commerce, and was

one of the thirteen

members of the

China Republican

Party (Singapore

branch).

Chia Yew Siang had

3 bungalows in

Pasir Panjang at the

site now occupied

by Bijou at Jalan

Mat Jambol. (see

map sketched by

his son, Chia Boon

Leong. The

compound is

outlined in red). He

had 6 wives during

his lifetime and

some of them lived

within the

compound with their

children.

Upon his death in

1930, he was buried

at Bukit Brown

cemetery. His family

recently cleared the

foliage around his

tomb, which had

become overgrown

during the last year

of Covid. They have

graciously shared a

photograph with us

here.

"During the Occupation, as far as I recall, I was not too worried. I did not know what was going on at that age, so there was no reason to be anxious," he said.

Mr Chia went from being at risk of execution to being selected for the Olympics in just six years.

But in the weeks to come, Mr Chia left his family home for Tiong Bahru, where his family felt they might be safer from the coming invasion.

He remained there throughout the Occupation.

While moving away from Pasir Panjang meant they escaped a fierce firefight - the battle of Bukit Chandu was fought not far away on Feb 14, 1942 - Mr Chia's family was still not far from danger in Tiong Bahru.

Eng Hoon Street, located about 130m away from where his family lived in Eng Watt Street, bore the brunt of Japanese shelling in the area, he said.

Within weeks of the British surrender on Feb 15, 1942, Mr Chia was told to report to an inspection site where Japanese soldiers screened Chinese men and took away those suspected of being anti-Japanese for execution.

The Japanese military operation, called Operation Sook Ching, saw Chinese males between the ages of 18 and 50 summoned to mass screening centres all over the island.

"Someone in Tiong Bahru said to report to an open area opposite the police station at the intersection of Keppel, Tanjong Pagar and Cantonment roads, so I went not knowing what was happening," said Mr Chia, who was 17 at that point.

"As a schoolboy I just carried on and followed instructions. We lined up, one by one, to face a Japanese soldier and some were told to go to a lorry, I did not know why then.

"It was only some time later that we were told those on the lorries were taken somewhere else to be executed."

Mr Chia said he later heard that his half-brother, a cousin, and a Pasir Panjang Rovers coach were taken away, and they were never seen again.

The Pasir Panjang Rovers team after winning the Alsagoff Shield in the Syonan Sports Association Soccer League in 1943. PHOTO

He also recalled another incident in Tiong Bahru Road: Japanese officers made a group of Chinese men line up as an informant, who wore a hood to hide his identity, pointed out those who had served under the British as members of a voluntary military reserve.

As the Occupation wore on and people got more used to living under Japanese rule, Mr Chia enrolled in a Japanese school in Queen Street in late 1942.

In mid-1943, as an 18-year-old, he worked for the Japanese in a telegraphy company, where he sent and received messages in morse code.

By that time, the Syonan Sports Association was formed, and Mr Chia recalled going to Jalan Besar Stadium to play football every day after work.

Beyond organising sports competitions, the association was a vehicle that mobilised auxiliary manpower to assist with various tasks, including clearing debris and casualties when bombings occurred.

As members of the association, Mr Chia and his Rovers teammates were tapped to help with such assignments, receiving rations of rice and cigarettes in exchange.

He said he enjoyed the camaraderie he shared with his teammates as they went about performing menial tasks, such as digging trenches at the Padang and planting tapioca in Holland Road.

"But the most important thing was that we got our rations," he said. "I didn't smoke so I sold my cigarettes for extra money."

On the pitch, the Rovers were a dominant force, winning all their matches between May to September 1943 to top the league.

But it was matches against Malayan opposition that Mr Chia remembers the most fondly.

Dinners served when the association hosted visiting teams were of a higher quality than everyday meals, which often comprised porridge and sweet potatoes.

Players rushed to get a share of the food when it was served.

At one dinner, a guest was peeved by such behaviour, and threw his dentures into a bowl of soup as soon as it was served so that no one else would have it.

"What did we do? We all had a good laugh," said Mr Chia.

Mr Chia said he enjoyed the camaraderie he shared with his teammates during the war.

On two occasions - in late 1943 and mid-1944 - Mr Chia was part of a Syonan team that made "goodwill" tours to Malaya, where it played against local teams.

Mr Chia recalled travelling by lorry between Kuala Lumpur and Ipoh on the second tour. The team feared attack by anti-Japanese guerrilla fighters targeting the Japanese officer who accompanied the team.

"Although it was not a comfortable trip, somehow the team still enjoyed ourselves," he said.

Between the Japanese surrender on Sept 2, 1945, and the surrender ceremony in Singapore on Sept 12, Mr Chia said the Japanese military remained in control and people were still fearful of them.

After hearing about the Japanese surrender, Mr Chia and his Rovers teammates gathered in a home in Lavender Street and celebrated loudly as they anticipated liberation from Japanese rule, only to be confronted by an armed Japanese soldier.

"We were lucky because we said we were celebrating a birthday and he left us alone," said Mr Chia.

After the war ended, he continued to play football, including for the Lien Hwa (United Chinese) team that toured Asia in December 1947.

The next year, he was selected to represent China in the Olympics, despite being Singapore-born.

The Chinese team would play just one match at the Games, losing to Turkey in the first knock-out round.

But Mr Chia, who started for the Chinese team, remains the only Singaporean to have taken the field in football at the Olympics.

Two other footballers went to the Olympics as part of the Chinese team - Chua Boon Lay in 1936 and Chu Chee Seng in 1948 - but never played.

Chia Boon Leong – The only Singaporean to play football at the Olympics

By Justin Kor

It was a chilly winter day on Nov 19, 1947 and skinny Chia Boon Leong could feel in his bones the winds blowing in from the Huangpu River. His young 22-year-old body was aching after touring with the Lien Hwa (United Chinese) team on a gruelling tour of 23 football matches in 42 days – a game every other day. Chia would be the only one to appear in all 23 games.

This time, he was up against Shanghai’s defending league champions, Tung Hwa, and it was his third match in four days in Shanghai. But fatigue had to wait. Chia was ready to strike. The tenacious inside left was everywhere on the pitch. One moment, the attacker was resolutely sprinting back into his own half to help out in defence.

The next one saw the lightning quick Singaporean dribble away with the ball. Coming up to an opponent, he nudged the ball to the right and feinted to his left. He left his opponent for dead, not knowing whether to chase man or ball. It was one of the dribbler’s many tricks.

His team won 5-3. A few months later, he was chosen to represent China in the 1948 Olympics in London, an achievement that has not been replicated by any other Singaporean.

To this day, he remains the only Singaporean footballer to have actually played at the Olympics, albeit under another country’s flag. Two others, fullback Chua Boon Lay and goalkeeper Chu Chee Seng, went to the Olympics but never played.

“Maybe it was the way the crowd reacted to my performance which made the Chinese officials decide to choose me for the London Olympics,” says Chia, who despite being the youngest and the smallest, was widely regarded as Lien Hwa’s best player.

Carnival of Canidrome

The runs during the Shanghai match kept him warm. Winter had just set in, with temperatures dipping to a chilly 5 degrees – not easy for a select group of boys from Malaya and Singapore who were more accustomed to the sweltering heat of the tropics. To combat the cold, they wore sweaters under their white jerseys and rubbed oil on their bodies.

But in the cold, Chia seemed to be a one-man furnace. The attacker’s stamina appeared limitless. “Somehow or another, I got comfortable with the cold,” he recalls. “Maybe it was the cold, I could run better.”

It went on like this for 90 minutes – he covered the length of the pitch to help his team in any way he could.

His industry charmed the home crowd, which was supposed to support home team Tung Hwa! At the now-demolished Canidrome – within the heart of the French Concession – the screaming and cheering capacity crowd of 12,000 had forgotten the civil war ravaging their country.

They were enamoured with the diminutive Chia, watching him pump his tiny frame – all of 160cm of it – up and down the field. They screamed and cheered every time he had the ball.

When the home team lost, the crowd didn’t mind. After the match, at least a hundred people surged towards Chia, mobbing him as he walked to the team bus. The crowd was so large that the police had to escort Chia out by another way out of the stadium.

“When the other players reached the crowd, they let them through. But when I reached them, they surrounded me,” says Chia with a laugh. “It took about 20 minutes for me to get on the bus. I was the last one on.”

More than 70 years later, Chia, now 93, still regards the match as the most memorable of his career. This despite him not scoring a goal.

“What I remembered most was not so much the game, but the post-match reception by the crowd. They were so natural and spontaneous. I still flush with pride whenever I think of this incident. It was a once in a lifetime feeling.”

1948 London

At the Olympic Games, the China national team played their only match against Turkey, with Chia in the starting 11. Despite their best efforts, they were trounced 4-0, unable to match the Turks in terms of strength and size. The Chinese team also saw their main striker lost to injury, and back in those days, no substitutions were allowed.

“The opponents were so big that we were bouncing off them in challenges, and they were very aggressive as well,” recalls Chia. Despite the loss, the Chinese team received praise in the local papers for their attractive style of play, with Chia in particular being mentioned for his speed and skills.

Back then, Chinese law stated that an ethnic Chinese could represent China, despite not being born in the country. This meant that although Chia was a British subject at that time, he was considered a Chinese national.

Chia also made unforgettable memories off the pitch. He counts marching past the royal family at London’s iconic Wembley Stadium during the opening ceremony as one of his most memorable moments.

“I was at the back of the contingent because I was the smallest,” he says with a smile.

He would later have a more intimate interaction with the royals, when he was the only player in the team selected to visit Buckingham Palace, where he would shake hands with King George VI, his wife Queen Elizabeth, and his mother, Queen Mary.

More than 60 years later, Chia would have another encounter with the royal family again in 2012, when he met Prince William and his wife Kate, in Singapore.

“When I told the prince I shook hands with his great-grandfather, he was very surprised. How many people in their lives can have the privilege to say something like that?”

Short Boy from Pasir Panjang

Chia’s background was more rustic than royal. Before he was terrorising defences in the region, he started his footballing journey by playing five-a-side matches with a tennis ball on a sandy pitch in front of his Pasir Panjang kampong house.

Playing with a tennis ball on a small pitch allowed him to develop his close ball control. “I had little coaching. The ball work came rather naturally to me – it was mostly self development.”

However, because of his small size, many thought he could never succeed as a football player. It only made him more determined to prove his doubters wrong.

“I had to strengthen my instinct for survival. I learnt how to be trickier, fitter, and faster to outwit the bigger opponents.”

What he lacked in physical presence, he made up for it with an indomitable spirit and enormous industry. And instead of relying on brawn, he used his head to play the game. Newspapers of the day often called him ‘the brains of the Singapore attack’.

Nicknamed ‘Twinkletoes’ because of his skilful ball control, he is widely regarded as one of the best football players in Malaya during the 1940s and 50s.

With him as the main orchestrator, Singapore won three Malaya Cups in a row from 1950 to 1952. His reward after winning the first Malaya Cup? “$10 dollar bonus and a celebratory dinner back in Singapore,” reveals Chia with a laugh.

In 1975, the New Nation newspaper lauded him as a player who was “swift as a hare, with brilliant ball control and unlimited stamina as his chief assets, he is a schemer of immense value to any forward line”.

His vital role to the team did not go unnoticed by supporters, who voted him as Malaya’s most popular footballer in 1954. His prize was a two-month training stint in England, where they managed to train at Arsenal, which was his favourite team growing up.

But at a relatively young age of 30 in 1955, he surprised many by retiring from the sport. “I noticed a lot of ex-players played until they weren’t good – I didn’t want that, to be booed out of the stadium by the crowd.”

Love for the game

Following retirement, Chia worked as a senior financial executive with radio service company Rediffusion. But with so much passion for the sport, it was difficult for him to completely exit the game. He returned to football in 1978 when he became a council member of the Football Association of Singapore (FAS).

At FAS, he was also team manager of the Singapore national team from 1978 to 1979, before heading the welfare committee of the council for seven months. He returned for a second stint as team manager before retiring in 1980.

Today, the football man is very much a family man, with a loving wife, three sons and two grandchildren. He still watches football on television, with his favourite player being Lionel Messi, whose built and style he could identify with. “He likes to challenge the opponent directly, in one-on-one situations,” said the dribbler of yore.

These days, Chia likes to garden and maintain his scrapbooks of old newspaper clippings of his footballing days. Once in a while, he would flip to match reports of that unforgettable match against Tung Hwa, scanning every sentence which brought him back to 1947.

“I’m very lucky to have gotten the best treatment as a footballer. I’m glad my wishes were fulfilled, or I wouldn’t have gone to places as diverse as Shanghai and London,” he says, recalling a time when most people in Singapore did not travel overseas.

“Regrets in life? Maybe only that I couldn’t watch myself on television to see how good I actually was,” he says with a smile.

Chia Boon Leong – The only Singaporean to play football at the Olympics

23-year-old Boon Leong in 1948

It was a chilly winter day on Nov 19, 1947 and skinny Chia Boon Leong could feel in his bones the winds blowing in from the Huangpu River. His young 22-year-old body was aching after touring with the Lien Hwa (United Chinese) team on a gruelling tour of 23 football matches in 42 days – a game every other day. Chia would be the only one to appear in all 23 games.

This time, he was up against Shanghai’s defending league champions, Tung Hwa, and it was his third match in four days in Shanghai. But fatigue had to wait. Chia was ready to strike. The tenacious inside left was everywhere on the pitch. One moment, the attacker was resolutely sprinting back into his own half to help out in defence.

The next one saw the lightning quick Singaporean dribble away with the ball. Coming up to an opponent, he nudged the ball to the right and feinted to his left. He left his opponent for dead, not knowing whether to chase man or ball. It was one of the dribbler’s many tricks.

His team won 5-3. A few months later, he was chosen to represent China in the 1948 Olympics in London, an achievement that has not been replicated by any other Singaporean.

To this day, he remains the only Singaporean footballer to have actually played at the Olympics, albeit under another country’s flag. Two others, fullback Chua Boon Lay and goalkeeper Chu Chee Seng, went to the Olympics but never played.

“Maybe it was the way the crowd reacted to my performance which made the Chinese officials decide to choose me for the London Olympics,” says Chia, who despite being the youngest and the smallest, was widely regarded as Lien Hwa’s best player.

The Lien Hwa Soccer Team of Malaya in 1947

Carnival of Canidrome

The runs during the Shanghai match kept him warm. Winter had just set in, with temperatures dipping to a chilly 5 degrees – not easy for a select group of boys from Malaya and Singapore who were more accustomed to the sweltering heat of the tropics. To combat the cold, they wore sweaters under their white jerseys and rubbed oil on their bodies.

But in the cold, Chia seemed to be a one-man furnace. The attacker’s stamina appeared limitless. “Somehow or another, I got comfortable with the cold,” he recalls. “Maybe it was the cold, I could run better.”

It went on like this for 90 minutes – he covered the length of the pitch to help his team in any way he could.

His industry charmed the home crowd, which was supposed to support home team Tung Hwa! At the now-demolished Canidrome – within the heart of the French Concession – the screaming and cheering capacity crowd of 12,000 had forgotten the civil war ravaging their country.

They were enamoured with the diminutive Chia, watching him pump his tiny frame – all of 160cm of it – up and down the field. They screamed and cheered every time he had the ball.

When the home team lost, the crowd didn’t mind. After the match, at least a hundred people surged towards Chia, mobbing him as he walked to the team bus. The crowd was so large that the police had to escort Chia out by another way out of the stadium.

“When the other players reached the crowd, they let them through. But when I reached them, they surrounded me,” says Chia with a laugh. “It took about 20 minutes for me to get on the bus. I was the last one on.”

More than 70 years later, Chia, now 93, still regards the match as the most memorable of his career. This despite him not scoring a goal.

“What I remembered most was not so much the game, but the post-match reception by the crowd. They were so natural and spontaneous. I still flush with pride whenever I think of this incident. It was a once in a lifetime feeling.”

1948 London

The 1948 China Olympic Football Team (Boon Leong is seated first row fourth from left)

At the Olympic Games, the China national team played their only match against Turkey, with Chia in the starting 11. Despite their best efforts, they were trounced 4-0, unable to match the Turks in terms of strength and size. The Chinese team also saw their main striker lost to injury, and back in those days, no substitutions were allowed.

“The opponents were so big that we were bouncing off them in challenges, and they were very aggressive as well,” recalls Chia. Despite the loss, the Chinese team received praise in the local papers for their attractive style of play, with Chia in particular being mentioned for his speed and skills.

Back then, Chinese law stated that an ethnic Chinese could represent China, despite not being born in the country. This meant that although Chia was a British subject at that time, he was considered a Chinese national.

Chia also made unforgettable memories off the pitch. He counts marching past the royal family at London’s iconic Wembley Stadium during the opening ceremony as one of his most memorable moments.

“I was at the back of the contingent because I was the smallest,” he says with a smile.

He would later have a more intimate interaction with the royals, when he was the only player in the team selected to visit Buckingham Palace, where he would shake hands with King George VI, his wife Queen Elizabeth, and his mother, Queen Mary.

More than 60 years later, Chia would have another encounter with the royal family again in 2012, when he met Prince William and his wife Kate, in Singapore.

“When I told the prince I shook hands with his great-grandfather, he was very surprised. How many people in their lives can have the privilege to say something like that?”

Short Boy from Pasir Panjang

Headlines describing Boon Leong in his heydays

Chia’s background was more rustic than royal. Before he was terrorising defences in the region, he started his footballing journey by playing five-a-side matches with a tennis ball on a sandy pitch in front of his Pasir Panjang kampong house.

Playing with a tennis ball on a small pitch allowed him to develop his close ball control. “I had little coaching. The ball work came rather naturally to me – it was mostly self development.”

However, because of his small size, many thought he could never succeed as a football player. It only made him more determined to prove his doubters wrong.

“I had to strengthen my instinct for survival. I learnt how to be trickier, fitter, and faster to outwit the bigger opponents.”

What he lacked in physical presence, he made up for it with an indomitable spirit and enormous industry. And instead of relying on brawn, he used his head to play the game. Newspapers of the day often called him ‘the brains of the Singapore attack’.

Nicknamed ‘Twinkletoes’ because of his skilful ball control, he is widely regarded as one of the best football players in Malaya during the 1940s and 50s.

With him as the main orchestrator, Singapore won three Malaya Cups in a row from 1950 to 1952. His reward after winning the first Malaya Cup? “$10 dollar bonus and a celebratory dinner back in Singapore,” reveals Chia with a laugh.

In 1975, the New Nation newspaper lauded him as a player who was “swift as a hare, with brilliant ball control and unlimited stamina as his chief assets, he is a schemer of immense value to any forward line”.

His vital role to the team did not go unnoticed by supporters, who voted him as Malaya’s most popular footballer in 1954. His prize was a two-month training stint in England, where they managed to train at Arsenal, which was his favourite team growing up.

But at a relatively young age of 30 in 1955, he surprised many by retiring from the sport. “I noticed a lot of ex-players played until they weren’t good – I didn’t want that, to be booed out of the stadium by the crowd.”

Love for the game

Following retirement, Chia worked as a senior financial executive with radio service company Rediffusion. But with so much passion for the sport, it was difficult for him to completely exit the game. He returned to football in 1978 when he became a council member of the Football Association of Singapore (FAS).

At FAS, he was also team manager of the Singapore national team from 1978 to 1979, before heading the welfare committee of the council for seven months. He returned for a second stint as team manager before retiring in 1980.

Today, the football man is very much a family man, with a loving wife, three sons and two grandchildren. He still watches football on television, with his favourite player being Lionel Messi, whose built and style he could identify with. “He likes to challenge the opponent directly, in one-on-one situations,” said the dribbler of yore.

Boon Leong and wife Li Choo with former SNOC President Mr Teo Chee Hean in 2005

These days, Chia likes to garden and maintain his scrapbooks of old newspaper clippings of his footballing days. Once in a while, he would flip to match reports of that unforgettable match against Tung Hwa, scanning every sentence which brought him back to 1947.

“I’m very lucky to have gotten the best treatment as a footballer. I’m glad my wishes were fulfilled, or I wouldn’t have gone to places as diverse as Shanghai and London,” he says, recalling a time when most people in Singapore did not travel overseas.

“Regrets in life? Maybe only that I couldn’t watch myself on television to see how good I actually was,” he says with a smile.

No comments:

Post a Comment