The rise and

demise of the

AAirpass,

American

Airlines’

$250k lifetime

ticket

In the 1980s, American

Airlines sold an unlimited

lifetime ticket, called the

AAirpass. They had no

idea what they’d gotten

themselves into.

Three decades ago, 28 lucky bastards managed to snag the greatest travel deal in history, courtesy of American Airlines. It was dubbed the “unlimited AAirpass.

For a one-time fee of $250k ($560k in 2018 dollars), this pass gave a buyer unlimited first-class travel for life. A companion pass could be purchased for an additional $150k, allowing the pass holder to bring along anyone for the ride.

Mark Cuban, an early AAirpasser, tells us it was “one of the best purchases [he’s] ever made.”

But the unlimited AAirpass had a fatal flaw: it was such a good deal that it ended up costing American Airlines millions of dollars per year — and the company set out to revoke the contracts of its top customers by any means necessary.

It was 1981, and American Airlines was in deep sh*t…

American had been hit hard by the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978. They’d posted a $76m loss in 1980, and were grappling with new competition, reduced ticket prices, and a changing industry that threatened to sink them into irrelevancy.

The airline’s newly-elected president, Robert Crandall, was on a mission to “cut American down to the bone” and lead a massive expansion from the ground up.

American needed cash, but interest rates were at a record-high. So, they came up with a different plan: they’d raise capital from their own customer base by selling its wealthiest customers the “ultimate travel perk” — an unlimited first-class ticket for life. The cost: $250k.

“The idea was that firms would buy this for their top performers,” Crandall tells us over the phone. “But as usual, the public is way smarter than any corporation. People immediately figured out we’d made a mistake pricing-wise.”

By 1994, American had discontinued the unlimited AAirpass — but not before 28 people got the deal of a lifetime.

Life with unlimited travel

Steve Rothstein, then an investment banker in Chicago, was already one of American Airlines’ top fliers when he was approached to buy the AAirpass in the early ‘80s.

“American Airlines contacted me and said that, based on the amount I traveled, the AAirpass would be a great purchase,” Rothstein tells us. “It was like a bond: instead of paying me dividends in cash, they were paying dividends in air travel. They needed cash, and they could pay me in miles.”

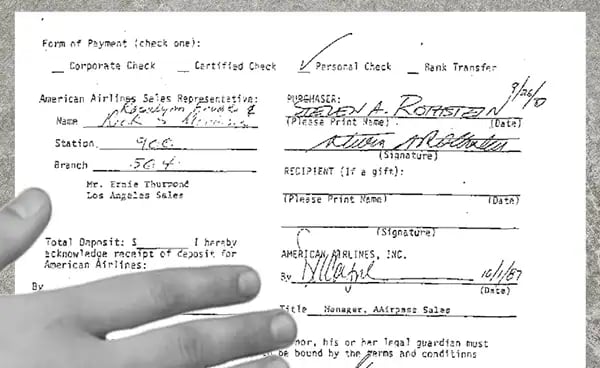

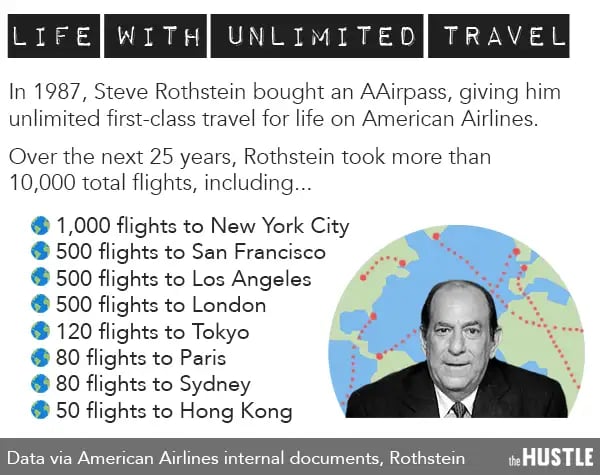

For a total of $383k, Rothstein purchased both the AAirpass and companion pass — and over the next 25 years, he proceeded to book more than 10k flights.

He took hundreds of trips to NYC, LA, and SF. He went to London — sometimes a dozen times per month. He flew up to Ontario just for a sandwich. On occasion, he’d offer his companion pass to a complete stranger at the airport.

“The contract was truly unlimited,” he says. “So why not use it as intended?”

Over in Texas, a direct marketing catalog consultant by the name of Jacques Vroom also decided to shell out the $400k for an AAirpass and companion pass.

“I had never bought anything for $400k in my life,” he tells us. “But I took out a loan for 12% for 5 years and did it, because I thought it would give me a competitive advantage for life.”

Over the next 2 decades, Vroom flew an average of 2m miles per year.

He used his pass to catch all of his son’s football games on the East Coast. He popped over to France or London just to have lunch with a friend. When his daughter had a middle school project on South American culture, he took her to Buenos Aires to see a rodeo and flew back the next day.

Like Rothstein, Vroom trusted the sanctity of the contract he’d signed with American Airlines: “They used the word ‘unlimited,’ and ‘lifetime,’” he says. “And then, the motherf*ckers took it all away.”

Yeahhh, about that promise…

Decades later, in 2007, American once again found itself in financial straits.

The company’s “revenue integrity team” found that AAirpass users cost the company big bucks — and they homed in on the program’s two most prolific users: Steve Rothstein and Jacques Vroom.

American calculated that Rothstein and Vroom were each costing the airline $1m per year in taxes, fees, and lost ticket sales.

It didn’t take long for the airline to find reasons to revoke the duo’s passes.

According to documents unearthed by Los Angeles Times reporter Ken Bensinger, Rothstein had made 3k reservations in a span of 4 years and canceled 2.5k of them; Vroom booked flights for strangers and allegedly accepted payment for tickets on certain occasions.

Neither of these practices was barred in the original contract. Nonetheless, American Airlines categorized them as “fraudulent activity,” and formed an elaborate operation to “take down” Rothstein and Vroom.

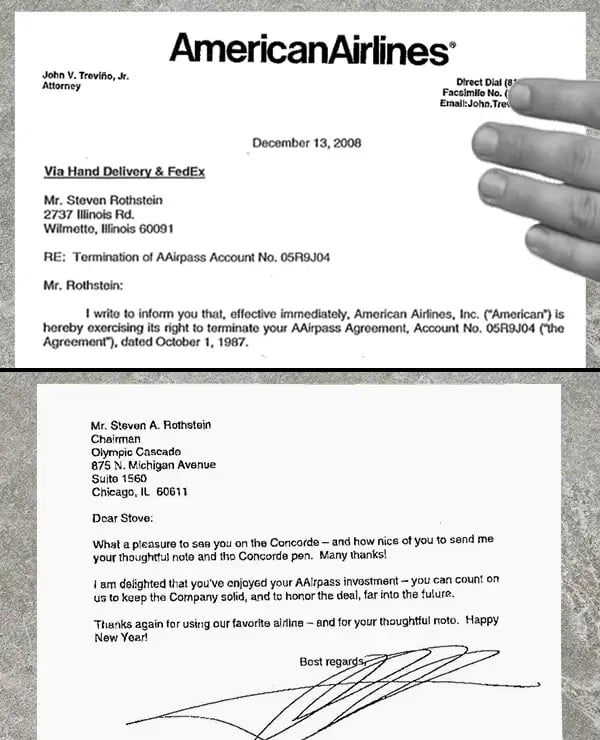

In July of 2008, Vroom was cornered by agents at London’s Heathrow airport; several months later, Rothstein was stopped while boarding a flight at Chicago O’Hare. Both men were stripped of their passes and told they’d never fly on the airline again.

Rothstein and Vroom both filed lawsuits against American Airlines for the wrongful termination of their contracts — but were outmatched by the airline’s “bazillion lawyers.” Then, in 2011, American filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, catapulting them into an indefinite legal limbo.

The corporation versus the measly millionaire

Neither Rothstein nor Vroom has recovered his AAirpass. A third customer also had his pass revoked; the other 25, including Mark Cuban’s, are still valid.

Now a substitute teacher in Dallas, Vroom has a theory. “American was hurting, and went after the most vulnerable AAirpass holders to free up cash — people they knew couldn’t fight back,” he says.

American Airlines declined to comment on this theory, or the program in general.

For Rothstein is a bit more conclusive about the whole thing: “I wish I’d never bought the thing,” he says.

On the walls of his New York office sits a 1998 letter from Robert Crandall, the ex-President of American Airlines: “You can count on us… to honor the deal far into the future.”

Today, Crandall has a different outlook on the situation: “I assume they were cheaters,” he tells us. “If they were cheaters, they deserved it.”

The desperation of the airline industry

Looking back, the AAirpass saga was a fledgling in the airline industry’s race to the bottom.

When the pass debuted in the ‘80s, we were entering a decade of decadence. Brands were competing for customers with amenities, luxuries, cushy promotions — hell, even hot meals.

Now, we’re in the era of begging for peanuts and a few inches of legroom. Flying is just another commodity, stripped to the bare bones by a market struggling to reduce overhead.

And in that market, there’s no room for men who fly to Paris just for lunch.

No comments:

Post a Comment