What is the History of Dysautonomia?

Dysautonomia has a long history, with documentation dating back to before 2000 BC in regions like China, India, and Indonesia. Each country had a similar name for the condition. In China it was known as ‘foot qi’, in Japan they called it ‘leg disease’, and in India and Indonesia it was named “bere-bere” which translates to “I can’t, I can’t”.

Over time the disease was found to be more common in cultures that consumed a lot of white rice. It has been discovered that the consumption of white rice can lead to thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency, a vitamin which is crucial for nervous system health. Its prevalence increased notably in the 1800s, particularly among navy personnel on long voyages.

In 1884 a Japanese naval doctor by the name of Kanehiro Takaki became aware of the ‘bere-bere’ disease becoming a major health issue in the Japanese navy, causing a high number of deaths. He conducted a critical study which involved embarking on a voyage and altering the sailors’ diet by reducing the amount of white rice they ate. His findings confirmed that the ‘berebere’ disease was linked to dietary habits, especially the consumption of white rice, which can lead to thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency. His research laid the groundwork for later discoveries of other contributing factors, including nerve damage, genetic disorders, blood loss, and histamine disorders. For more information, read Top 9 things⁰¹ you need to know about dysautonomia.

Notes ⁰¹:

Dysautonomia

1. Dysautonomia involves the ANS (autonomic nervous system)

2. Dysautonomia is a breakdown of the ANS

3. There are multiple types of dysautonomia

4. Dysautonomia has a wide range of symptoms

5. It can be a little tricky to get a dysautonomia diagnosis

6. Dysautonomia can be primary or secondary

7. Dysautonomia has a rich history

8. Long covid has been linked to the rise in dysautonomia cases

9. There is hope

Dysautonomia is becoming increasingly common; currently over 70 million people worldwide experience the condition. Yet, even though dysautonomia is quickly becoming a household name, there is still a lot of confusion and misinformation around what it is, what causes it, and how it presents.

This confusion is especially common because dysautonomia is an “invisible illness” - a type of chronic illness where the people who suffer from it may not appear sick. Due to the number of people afflicted by dysautonomia, it’s likely that you or someone you know has been impacted by it.

To answer some of your questions - here are the top 9 things you need to know about dysautonomia.

What treatment options are available for dysautonomia?

Dysautonomia is a condition where there is a dysfunction in the autonomic nervous system (ANS) which controls unconscious body functions such as breathing, blood pressure, and digestion.

How do I know if I have dysautonomia? If you’re reading this, it is likely because you or someone you know is dealing with physical and/or mental symptoms that cannot be explained by their Family Practitioners. Those same well meaning practitioners’ diagnosis and treatment plans are often even less helpful.

1. Dysautonomia involves the ANS

Dysautonomia occurs when there is dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), so in order to understand what dysautonomia is, we have to first get a concept of the ANS. The autonomic nervous system is a matrix of nerves throughout the body that connect your brain to your organs.

In fact, the ANS is entwined with almost every organ and system in your body. This allows control of your subconscious body functions such as breathing, heart rate, blood pressure, digestion, and many more. These are all processes that run in the background - you don’t have to think about them in order for them to continue; they keep working even when you are asleep.

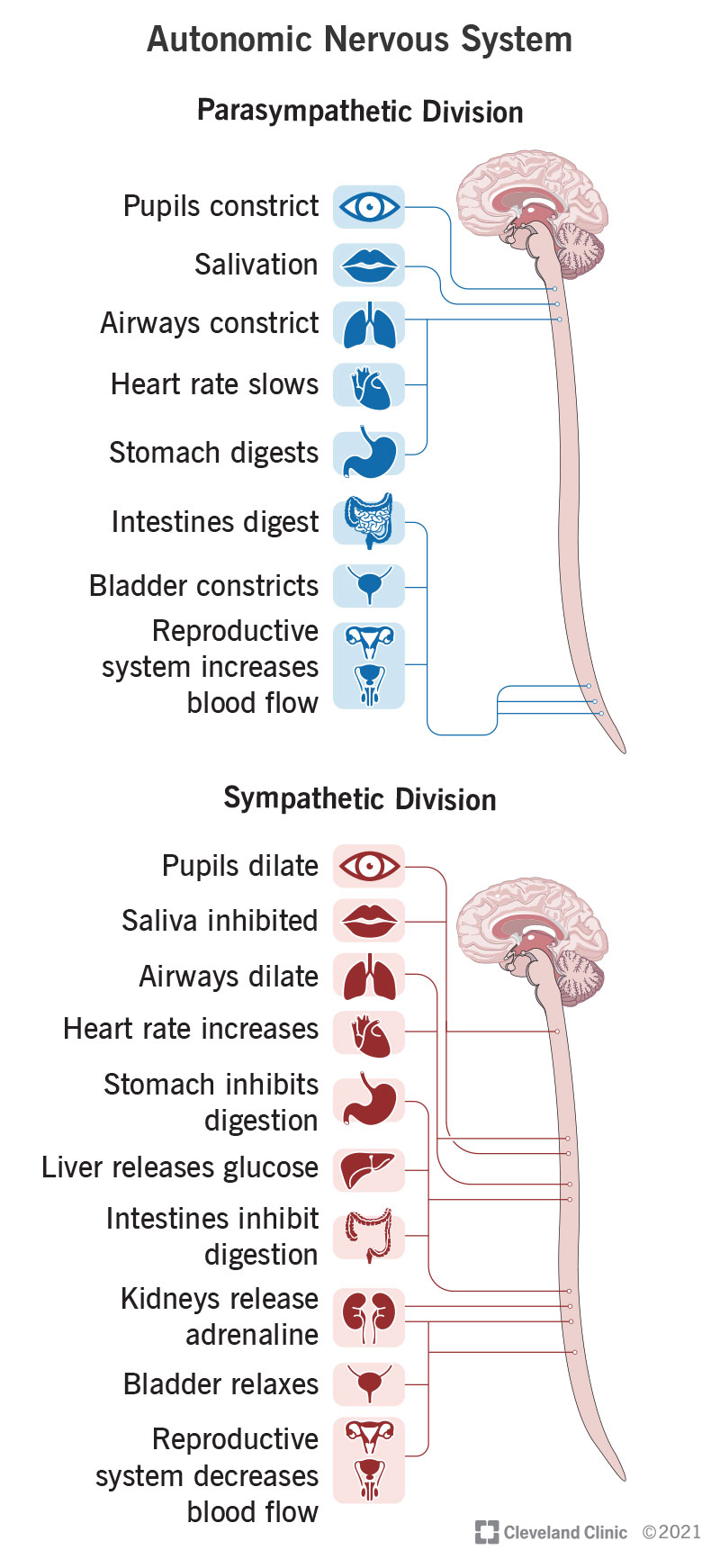

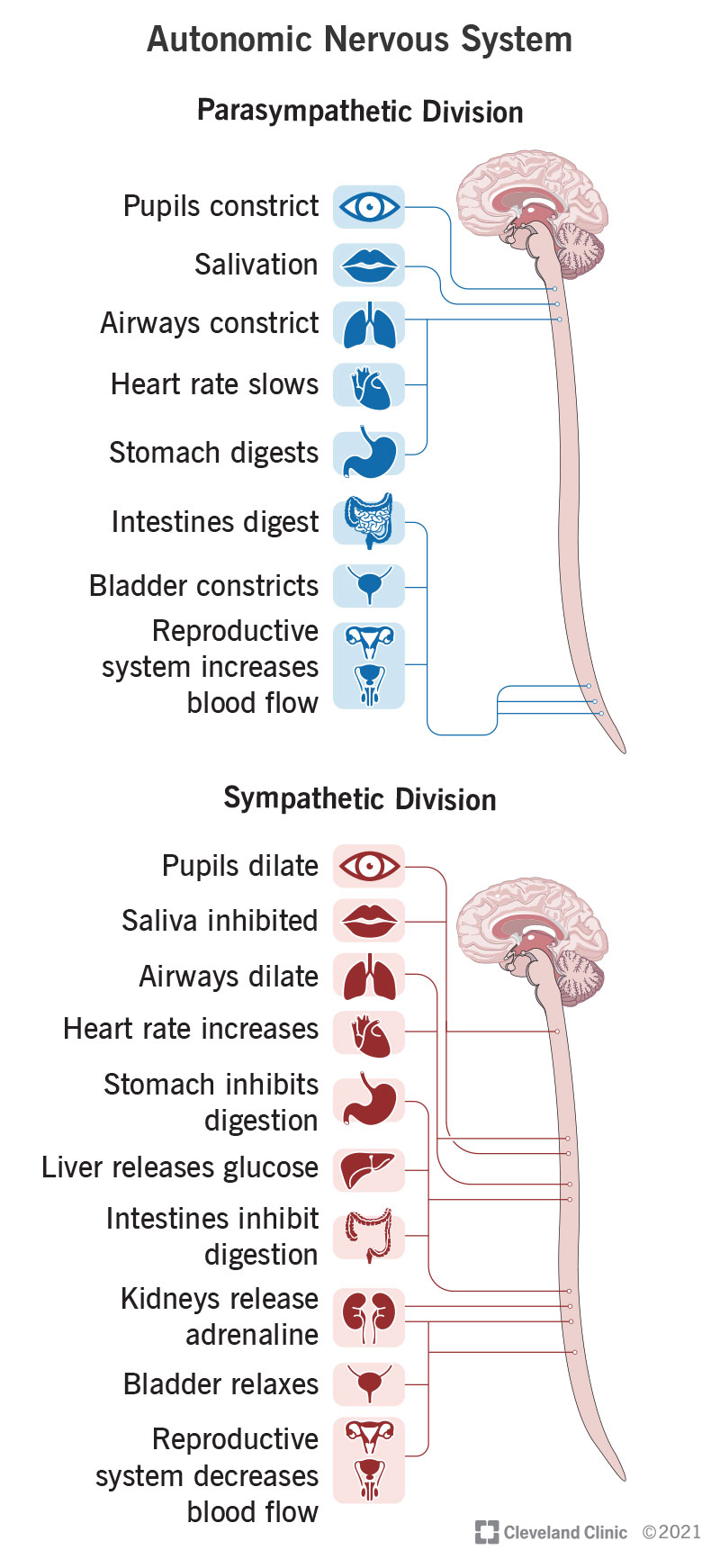

The ANS further divides into two branches known as the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. These two branches work oppositely of each other to maintain balance in the body.

You can think of the sympathetic nervous system like the “gas pedal” of your body; it revs things up and allows you to escape from danger (the fight or flight response). On the flip side, you have the parasympathetic nervous system which works like your body’s “brake pedal”; it calms things down (the rest and digest functions).

In a healthy, functioning body, these two systems work together to keep all of your organ systems running smoothly (Cleveland Clinic).

So what happens when this system isn’t balanced and working the way it’s supposed to? Enter: dysautonomia.

2. Dysautonomia is a breakdown of the ANS

Let’s keep going with our car analogy. Imagine driving somewhere, and as you’re driving you alternate between using your gas and brake pedals. This allows you to maintain a safe driving speed, stop at appropriate places, or accelerate quickly to get out of the way of potential mishap.

How well do you think you could drive if your brake lines were cut, and it was impossible for you to stop when you needed to? Or if, in addition to no brakes, there was a brick on your gas pedal hurtling you at breakneck speeds down the road, and you could only attempt control with wild steering? What if you were trying to drive with both your gas and brake pedals completely floored at the same time?

Just as these would not be safe or functional ways to drive, when our body’s “gas and brake pedals” (the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems) are not functioning the way they are supposed to, it can wreak havoc.

Dysautonomia, then, is the name for any condition that disrupts the autonomic nervous system. It can range in severity from extremely mild to debilitating, and can affect a variety of organs. Dysautonomia is sometimes also referred to as autonomic dysfunction or autonomic neuropathy (Cleveland Clinic).

Since dysautonomia is a condition of the nervous system which primarily affects internal organs, this is what contributes to it being considered an “invisible illness”. However, this doesn’t mean that those who have this condition are faking or playing up their symptoms and struggles!

Even though outward signs of the condition are less common, the impact on quality of life can be enormous. Just as with any other illness, those with dysautonomia need compassion and support, even if you don’t see physical manifestations of their condition.

3. There are multiple types of dysautonomia

Dysautonomia is an umbrella term for many conditions of the autonomic nervous system. It involves a broad spectrum of symptoms and severities, which can significantly impact daily living. It is also possible to experience and be diagnosed with more than one type of dysautonomia at a time. A few of these conditions include the following:

Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) – Characterized by an excessive heart rate increase upon standing among other symptoms. This is the most common form of dysautonomia, with an estimated 500,000-3 million Americans having the condition.

Orthostatic Hypotension (OH) – A form of low blood pressure that happens when standing up from sitting or lying down.

Vasovagal Syncope (VVS) – Also known as neurally mediated syncope (NMS), this is a common form of fainting that occurs in response to a trigger, such as prolonged standing or emotional stress.

Inappropriate Sinus Tachycardia (ISA) – A chronic condition where the heart rate is over 100 beats per minute while at rest.

Autoimmune Autonomic Ganglionopathy (AAG) – Also known as acute pandysautonomia, characterized by orthostatic hypotension, numbness in the hands and feet, among other symptoms.

Baroreflex Failure – Happens when there is a failure of the baroreflex mechanism, which helps maintain a stable blood pressure.

Familial Dysautonomia (Riley-Day Syndrome) – A rare genetic disorder that affects the sensory and autonomic nervous systems.

Pure Autonomic Failure (PAF) – A degenerative disease of the autonomic nervous system that causes severe orthostatic hypotension.

Multiple System Atrophy (MSA) – A progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by autonomic dysfunction and motor impairment.(Dysautonomia Support)

4. Dysautonomia has a wide range of symptoms

Think again about all of the body systems that the ANS is involved in (essentially all of them). Because of this, dysautonomia can look different based on which organs are involved.

The primary symptoms that most people experience are:

● Fatigue

● Dizziness

● Brain fog

● Shortness of breath

● Difficulty sleeping

● Poor circulation and blood pooling in feet and legs

However this can vary from person to person. If your eyes are affected by your nervous system dysfunction, you may experience vision changes, blurriness, wide or pinpoint pupils, and dry or watery eyes.

If your cardiovascular system is being affected, you may have tachycardia, blood pressure changes, or blood pooling in your legs and feet.

The symptoms of dysautonomia can seem extremely varied and disconnected, which is why seeing a practitioner who understands dysautonomia is very important (Cleveland Clinic).

5. It can be a little tricky to get a dysautonomia diagnosis

What do headaches, poor digestion, and heart palpitations have in common? This seeming disconnection between symptoms can be one of the struggles when trying to get dysautonomia diagnosed. Many physicians hyper-specialize in their own areas - neurology, gastroenterology, cardiology, and so on.

But, of course, all of those symptoms and systems are connected to the ANS. Unfortunately, when a condition such as dysautonomia is present, there’s not just a single system or organ involved; a full body picture is necessary to truly understand what’s going on.

Because of this, finding a physician who is familiar with (or even specializes in) dysautonomia is essential to receiving prompt and adequate care. The types of physicians who treat dysautonomia range across many specialties, but the most common are neuromuscular doctors, cardiologists, and neurologists. Organizations such as The Dysautonomia Project have physician finder links to assist individuals in finding a provider near them.

Once an appropriate physician has been located, they are able to walk clients through the specific tests that can be helpful in obtaining a diagnosis. Often, dysautonomia is a diagnosis of exclusion, and it can take quite a bit of time and teamwork to obtain an official diagnosis (Cleveland Clinic).

6. Dysautonomia can be primary or secondary

“Primary” dysautonomia means that it happens on its own, without a specific cause. One of these is familial dysautonomia - an inherited genetic condition. Certain demographics are at higher risk for familial dysautonomia, and that may be taken into consideration when seeking a diagnosis. “Idiopathic” dysautonomia is also considered a primary form of the condition; medical professionals don’t know what caused it, so it’s placed in this category (Cleveland Clinic).

Far more commonly, dysautonomia is “secondary”, meaning it has a specific condition that caused or contributed to it. There are many of these conditions, some of which include:

● COVID-19

● Lyme

● EDS and other connective tissue disorders

● MS

● Toxins such as mold or heavy metals

● Lupus

● Traumatic brain injury

And many more

(Cleveland Clinic)

Many people with dysautonomia are able to link the beginning of their illness to a “trigger” event (or, more often, a “perfect storm” of events). As the cause can be extremely varied, it can be helpful to determine what the root cause of the condition was and when the trigger event occurred. Despite the diversity of causes, however, the approach to managing dysautonomia tends to follow a unified path focusing on re-regulating the nervous system.

7. Dysautonomia has a rich history

We often think of conditions such as dysautonomia as new problems, unique to our modern society. However, even though there wasn’t a name for it yet, many historical cases describe what we now believe to have been dysautonomia. Even the accounts of King David in the 10th century BC seem to be consistent with symptoms that can be caused by dysautonomia - primarily difficulty with his balance and temperature regulation (Very Well Health).

In the late 19th century, the dysautonomic condition “beriberi” (translated to “I can’t, I can’t”) became prevalent among the Japanese navy, causing a high number of deaths. Japanese naval doctor Kanehiro Takaki made major breakthroughs with his research, finding that officers who ate a varied diet with more protein were less likely to develop the condition than the soldiers who ate primarily white rice. By altering the sailors' diets, he was able to drastically reduce the number and severity of beriberi cases on the voyage.

His study was one of the first to indicate that beriberi was not an infectious disease, as previously thought, but rather a nutritional deficiency. His research laid the groundwork for later progress, including the discovery of vitamins. (The James Lind Library).

What we now understand about Takaki’s findings is that a diet low in meat and high in white rice causes thiamine (B1) deficiency. This vitamin deficiency, in turn, is responsible for the symptoms of beriberi. The role of thiamine deficiency in dysautonomia has been well-documented, and the reversal of this deficiency can be key in treating the condition (Lonsdale, 2006).

8. Long covid has been linked to the rise in dysautonomia cases

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, a demographic of people who experience long COVID has emerged. According to CDC numbers from 2022, 7.5% of US adults experienced long covid symptoms. In order to be considered long COVID, these symptoms lasted three months or longer from the time of initial infection, and were not present before the illness happened (CDC).

In early 2022 the journal Frontiers in Neurology published a study evaluating the link between long COVID and dysautonomia. What they discovered is that, of the 2,314 global long COVID sufferers they surveyed, 67% were found to have moderate to severe autonomic dysfunction. As mentioned in the beginning of this post, there are now 70 million people worldwide afflicted with dysautonomia, many of whom experienced COVID-19 as their trigger event (News Medical).

9. There is hope

Everything you’ve learned about dysautonomia up until this point may seem incredibly daunting. In truth, the modern western medical belief is that dysautonomia is an incurable, lifelong chronic illness. For some, it’s no more than a slight annoyance; for others, it can be a debilitating condition that leads to becoming bedridden.

If you or someone you love is affected by dysautonomia it can be frustrating, isolating, even terrifying. However, thanks to the internet, online support groups and communities are popping up, allowing people to connect with others who truly understand what they are going through.

Furthermore, many who find themselves experiencing the trials of dysautonomia are turning to more holistic approaches to manage their symptoms and improve their overall health. There are many who have successfully put their dysautonomia into remission for years through dietary, lifestyle, and nervous system regulation practices.

We have found that education, support, and holistic care are the cornerstones of helping people manage their dysautonomia symptoms.

Autonomic Nervous System

Your autonomic nervous system is a network of nerves throughout your body that control unconscious processes. These are things that happen without you thinking about them, such as breathing and your heart beating. Your autonomic nervous system is always active, even when you’re asleep, and it’s key to your continued survival.

Your autonomic nervous system controls your body’s automatic processes, with divisions to activate processes and relax them.

Overview

The autonomic nervous system manages body processes you don’t think about. Those processes include heartbeat, blood pressure, digestion and more.

What is the autonomic nervous system?

Your autonomic nervous system is a part of your overall nervous system that controls the automatic functions of your body that you need to survive. These are processes you don’t think about and that your brain manages while you’re awake or asleep.

Where does the autonomic nervous system fit in the overall structure of the nervous system?

Your overall nervous system includes two main subsystems:

Central nervous system: This includes your brain (your retina and optic nerve in your eyes are considered part of your brain, structure-wise) and spinal cord.

Peripheral nervous system: This includes every part of your nervous system that isn’t your brain and spinal cord.

Your peripheral nervous system also has two subsystems:

Somatic nervous system: This includes muscles you can control, plus all the nerves throughout your body that carry information from your senses. That sensory information includes sound, smell, taste and touch. Vision doesn’t fall under this because the parts of your eyes that manage your sight are part of your brain.

Autonomic nervous system: This is the part of your nervous system that connects your brain to most of your internal organs.

What does the autonomic nervous system do?

Your autonomic nervous system breaks down into three divisions, each with its own job:

Sympathetic nervous system: This system activates body processes that help you in times of need, especially times of stress or danger. This system is responsible for your body’s “fight-or-flight” response.

Parasympathetic nervous system: This part of your autonomic nervous system does the opposite of your sympathetic nervous system. This system is responsible for the “rest-and-digest” body processes.

Enteric nervous system: This part of your autonomic nervous system manages how your body digests food.

How does the autonomic nervous system help with other organs?

Much like a home needs electrical wiring to control lights and everything inside that needs power, your brain needs the autonomic nervous system’s network of nerves. These nerves are the physical connections your brain needs to control almost all of your major internal organs.

Organ functions controlled through your autonomic nervous system

Your autonomic nervous system has the following effects on your body’s systems:

Eyes: Your autonomic nervous system doesn’t involve your vision directly. However, it does manage the width of your pupils (regulating how much light enters your eyes) and the muscles your eyes use to focus.

Lacrimal (eyes), nasopharyngeal (nose) and salivary (mouth) glands: Your autonomic nervous system controls your tear system around your eyes, how your nose runs and when your mouth waters.

Skin: Your autonomic nervous system controls your body’s ability to sweat. It also controls the muscles that cause hair to stand up. This reaction is commonly called “goosebumps” or “gooseflesh.”

Heart and circulatory system: The autonomic nervous system regulates how fast and hard your heart pumps and the width of blood vessels. Those abilities are how your autonomic system helps manage your heart rate and blood pressure.

Immune system: Your parasympathetic nervous system can trigger reactions from your immune system. That can happen with infections, asthma attacks and allergic reactions, to name a few.

Lungs: Your autonomic nervous system manages the width of your airway and the network of passages that carry air into and out of your lungs.

Intestines and colon: Your autonomic nervous system manages the digestion process from your small intestine to your colon. Your autonomic nervous system also holds the muscles closed at your rectum until you’re ready to relieve yourself and defecate (poop).

Liver and pancreas: Your autonomic nervous system regulates when your pancreas releases insulin and other hormones, and when your liver converts different molecules that hold stored energy into glucose that your cells can use.

Urinary tract: Your autonomic nervous system manages your bladder muscles, including the muscles that hold it closed until you're ready to relieve yourself and urinate (pee).

Reproductive system: Your autonomic system plays a key role in your body’s sexual functions, including feeling aroused (erections and secreting fluids that provide lubrication during sex) and the ability to orgasm.

What are some interesting facts about the autonomic nervous system?

Your sympathetic and parasympathetic systems create a balancing act. Your sympathetic nervous system activates body processes, and your parasympathetic deactivates or lowers them. That balance is key to your body's well-being and your ongoing survival.

It involves multiple forms of communication. Your nervous system uses chemical compounds produced by various glands in your body and brain as signals for communication. It also uses electrical energy in the neurons themselves. The neurons switch back and forth between electrical and chemical communication as needed.

Your enteric nervous system is very complex. Some experts describe it as part of the overall nervous system instead of the autonomic nervous system. That’s because there are as many neurons (specialized cells that make up your brain, spinal cord and nerves) in your enteric nervous system as there are in your spinal cord.

Anatomy

Where is it located?

Your autonomic nervous system includes a network of nerves that extend throughout your head and body. Some of those nerves extend directly out from your brain, while others extend out from your spinal cord, which relays signals from your brain into those nerves.

There are 12 cranial nerves, which use Roman numerals to set them apart, and your autonomic nervous system has nerve fibers in four of them. These include the third, seventh, ninth and 10th cranial nerves. They manage pupil dilation, eye focusing, tears, nasal mucus, saliva and organs in your chest and belly.

Your autonomic nervous system also uses most of the 31 spinal nerves. These include spinal nerves in your thoracic (chest and upper back), lumbar (lower back) and sacral (tailbone).

The spinal nerve connections are how your autonomic system controls the following:

Heart.

Lungs.

Liver.

Pancreas.

Spleen.

Stomach.

Small and large intestine.

Colon.

Kidney.

Bladder.

Sexual organs.

The part of your brain that runs autonomic functions is your hypothalamus. This structure isn’t part of your autonomic nervous system, but is a key part of how it works.

What is it made of?

Your autonomic nervous system has a similar makeup to your overall nervous system. The main cell types are as follows, with more about them listed below:

Neurons: These cells send and relay signals, and makeup parts of your brain, spinal cord and nerves. They also convert signals between the chemical and electrical forms.

Glial cells: These cells don’t transmit or relay nervous system signals. Instead, they’re helpers or support cells for the neurons.

Nuclei: These are nerve cell clusters grouped together because they have the same jobs or connections.

Ganglia: These, pronounced “gang-lee-uh,” are groups of related nerve cells (one of these is a ganglion, pronounced “gang-lee-on”). They usually don’t all have the same jobs or connections, but they’re in roughly the same area or have connections to the same systems. Examples of this are the cochlear and vestibular ganglia, which are part of your senses of hearing and balance.

Neurons

Each neuron consists of the following:

Cell body: This is the main part of the cell.

Axon: This is a long, arm-like extension. At the end of an axon are several finger-like extensions where the electrical signal in the neuron becomes a chemical signal. These extensions, or synapses, connect with nearby nerve cells.

Dendrites: These are small branch-like extensions (their name comes from a Latin word that means “tree-like”) on the cell body. Dendrites receive the chemical signals sent from synapses of other nearby neurons.

Myelin: This is a thin layer composed of fatty compounds. Myelin is a protective covering that surrounds the axon of many neurons.

The dendrites on a single neuron may connect to thousands of other synapses. Some neurons are longer or shorter, depending on their location in your body and what they do.

Glial cells

Glial (pronounced “glee-uhl”) cells do several different jobs. They help develop and maintain neurons when you’re young and manage how neurons work throughout your life. They shield your nervous system from infections, control the chemical balance in your nervous system and coat neurons’ axons with myelin. There are 10 times more glial cells than neurons.

Conditions and Disorders

What are the common conditions and disorders that affect the autonomic nervous system?

There are many conditions and causes of autonomic neuropathy, which means damage or disease that affects your autonomic nervous system. Common examples include:

Type 2 diabetes. Unmanaged type 2 diabetes can damage your autonomic nervous system over time. An example of this is orthostatic hypotension, where your blood pressure drops when you stand up. Diabetic neuropathy can damage the nerves that normally trigger a blood pressure increase reflex when you stand.

Amyloidosis. This condition causes long-term nerve damage because malfunctioning protein molecules build up in various parts of your body.

Autoimmune and inflammatory conditions. A major example of this is Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Congenital and genetic conditions. These are disorders or conditions you have at birth. You have genetic conditions because you inherit them from one or both parents. An example of this is Hirschsprung’s disease.

Infections. Nerve damage can happen because of viruses such as HIV or bacteria from insect bites that cause Lyme disease or Chagas disease. Other infections that can also do this include botulism or tetanus.

Multiple system atrophy.This severe condition is similar to Parkinson’s disease, damaging autonomic nerves over time.

Poisons and toxins. Toxic heavy metals like mercury or lead can damage autonomic nerves. Many industrial chemicals can also cause this kind of damage. Alcohol can also have toxic effects on your autonomic nerves.

Trauma. Injuries can cause nerve damage, which may be long-term or even permanent. This is especially the case when you have injuries to your spinal cord that damage or cut off autonomic connections farther down.

Tumors. Cancer and benign (harmless) growths can both disrupt your autonomic nervous system.

Common signs or symptoms of body organ conditions?

The symptoms of autonomic nervous system conditions depend on the location of the damage. With conditions like Type 2 diabetes, the damage can happen in many places throughout your body. The most likely symptoms of autonomic nervous system damage include:

● Heart rhythm problems (including arrhythmias).

● Dizziness or passing out when standing up.

● Trouble swallowing (dysphagia).

● Trouble digesting food (including gastroparesis).

● Constipation.

● Incontinence (bladder or bowel).

● Sexual dysfunction.

● Sweating too much (hyperhidrosis) or not sweating enough (anhidrosis).

● Problems tolerating hot temperatures.

Common tests to check the health of the body organ?

Several tests can help in diagnosing autonomic nervous system problems. These include:

● Blood tests (these can detect many problems, ranging from immune system problems to toxins and poisons, especially metals like mercury or lead).

● Electrocardiogram (EKG).

● Electroencephalogram (EEG).

● Electromyogram (nerve conduction test).

● Genetic testing.

● Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Common treatments for the body organ?

The treatments for autonomic nervous system conditions can be very specific, depending on the condition in question. Some of them might treat the condition itself or an underlying cause. Others might only treat symptoms of the condition, especially when there’s no cure or treatment for the condition. That means there isn’t a one-treatment-fits-all approach to these conditions. Medications can help with some of these conditions, but not all of them.

Care

How can I prevent autonomic nervous system conditions and problems?

Prevention of autonomic nervous system damage is the best way to avoid conditions that affect that system. The best preventive actions you can take include:

Eat a balanced diet. Vitamin deficiencies, especially vitamin B12, can damage your autonomic nervous system.

Avoid abusing drugs and alcohol.Abusing prescription and recreational drugs, as well as alcohol, can damage your autonomic nervous system.

Stay physically active and maintain a healthy weight. This can also help prevent or delay the onset of Type 2 diabetes, which damages your autonomic nerves over time. It can also help you avoid injuries that might damage areas of your spinal cord that could have autonomic nervous system impacts.

Wear safety equipment as needed.Injuries are a major source of nerve damage. Using safety equipment during work and play activities can protect you from these types of injuries, or limit the severity of the injuries.

Manage chronic conditions as recommended. If you have a chronic condition that can affect your autonomic nerves — especially Type 2 diabetes — you should take steps to manage this condition. That can limit the effects of the condition or delay how long it takes to get worse. Your healthcare provider can help guide you on ways to manage this condition.

Your autonomic nervous system is a vital part of how you live your life. You don’t even have to think about it most of the time and it will keep doing its job. Taking care of your body, especially your nervous system, is the best way to avoid conditions that can cause autonomic nerve damage. That way, you can keep focusing on what you want to pay attention to in your life.

Overview

Dysautonomia is an umbrella term encompassing different conditions affecting the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS). Imagine the body as a complex network of highways where traffic signals are essential to smoothly regulate the flow of cars. If those signals start to malfunction, the traffic would become chaotic and unpredictable. This is similar to what happens in dysautonomia, it is a condition where the body’s internal “traffic signals” – the autonomic nervous system (ANS) – do not work as they should, leading to various symptoms and difficulties.

Dysautonomia is a significant disruption in how the body’s automatic processes are regulated. It is a complex condition where the autonomic nervous system (ANS) is out of balance, primarily showing an excessive activation of the parasympathetic (fight or flight) system. This imbalance can affect various body systems, leading to issues with immune system regulation, respiratory rate (when awake and while sleeping), bowel movements, balance, equilibrium, memory, attention, sleep patterns, temperature control, hormonal balance, and nutrient absorption. Despite consuming sufficient nutrients, individuals with dysautonomia may experience deficiencies due to this autonomic disruption.

What are the Symptoms of Dysautonomia?

Dysautonomia can present a wide range of symptoms that can vary greatly from person to person. Here are some common symptoms experienced by those with the condition:

● Extreme Fatigue: Many people with dysautonomia experience debilitating fatigue, sometimes being bedridden and unable to perform simple tasks like using the bathroom or getting a glass of water. This is often misdiagnosed as adrenal fatigue.

● Heart Palpitations: Erratic heart rates, especially when lying down, moving, sitting, or standing, are common. This can be alarming and may lead to frequent ER visits despite normal test results. Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) is a frequent symptom.

● Visible Signs: Poor blood flow can cause parts of the body, particularly the feet and legs, to turn purple or pink. Other visible signs include dry skin and acne-like blemishes.

● Sensitivities: Individuals often have extreme sensitivities to light, sound, heat, and cold. These sensitivities can cause significant discomfort, such as eye strain, the need for sunglasses indoors, and severe anxiety from minor temperature changes.

● Cognitive and Physical Impairment: Cognitive functions like memory and focus are often impaired, creating a “haze” or brain fog. Physical activities can become very challenging, and there is a frequent need to take breaks and rest.

● Daily Function Challenges: Everyday tasks become extremely difficult, feeling like moving with heavy weights. Standing for too long can cause dizziness or a feeling of faintness, and muscle pain can make activities like climbing stairs or opening jars nearly impossible.

● Sleep Issues: Sleep patterns are often disrupted, leading to non-restorative sleep. Insomnia is common, making it difficult to wake up even with alarms.

● Immune System Deregulation: Frequent infections and severe autoimmune responses are common. Clients may experience repeated sinus infections, ear infections, and other illnesses.

● Unpredictable Daily Functioning: The variability of symptoms makes it hard to plan activities, as the ability to participate can change dramatically from day to day. Feeling well enough to go out often results in a host of symptoms upon returning home.

These symptoms collectively create a challenging daily life for individuals with dysautonomia, significantly impacting their overall quality of life.

What Causes Dysautonomia?

Dysautonomia can be triggered by various factors, including infections, childbirth complications, head injuries, significant blood loss, and hereditary factors. Common comorbid conditions include Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) and MTHFR gene mutations. Despite the diversity in causes, the approach to managing dysautonomia typically involves re-regulating the nervous system.

No comments:

Post a Comment