Howard Gardner’s 9 Types of Intelligence (Examples)

Are you intelligent?

The answer to that might be more complicated than you think. Many people can say “yes” and they can say “no” at the same time!

Why? Because there isn’t just one way to be intelligent. Some, like Harvard psychologist Howard Gardner, say that there are nine types of intelligence. His work is a response to earlier theories of intelligence, that suggested that there was just one type of general intelligence.

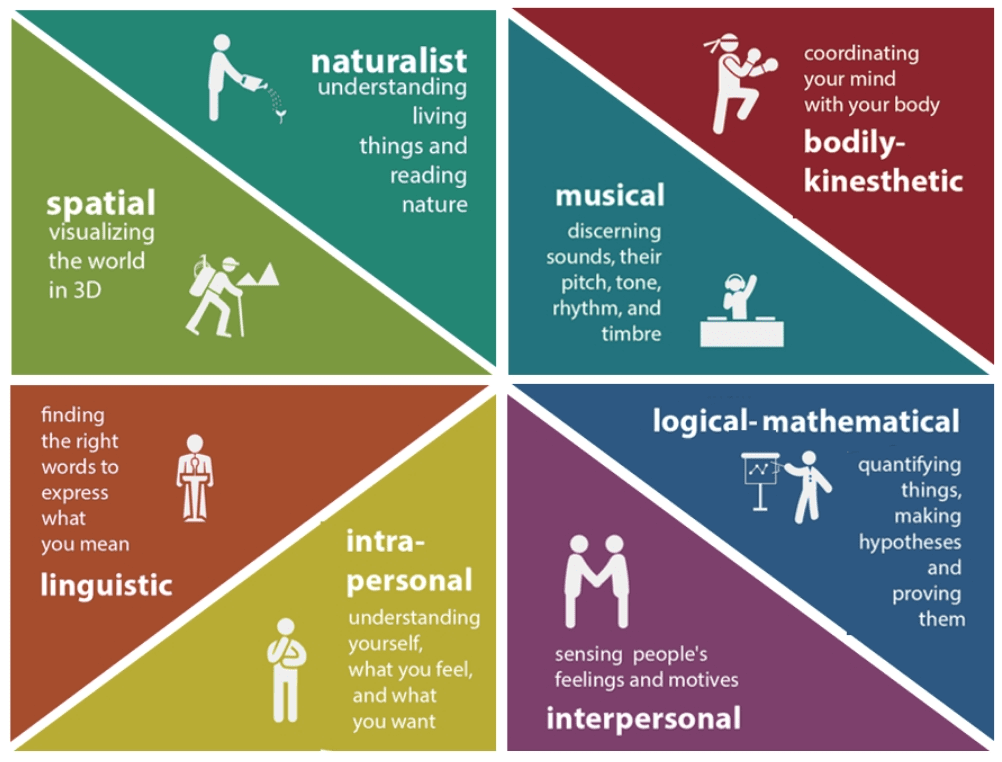

What Are The Nine Types of Intelligence?

1 Visual-spatial intelligence

2 Linguistic-verbal intelligence

3 Mathematical intelligence

4 Kinesthetic intelligence

5 Musical intelligence

6 Interpersonal intelligence

7 Intrapersonal intelligence

8 Naturalistic intelligence

9 Existential intelligence

1 Visual-spatial intelligence

Visual-spatial intelligence is the ability to create, understand, or process visual information. If you’ve ever met someone who can look at a blueprint and design a whole room, you can guess that they have high visual-spatial intelligence.

Here’s an example of when this comes in handy. You get a new nightstand - but you have to assemble it. When you open up the assembly instructions, you don’t see any words. Just pictures! If you have high visual-spatial intelligence, this won’t be a problem. You’ll still be able to put together that nightstand.

2 Linguistic-verbal intelligence

If you have high linguistic-verbal intelligence, those instructions probably wouldn’t get you too far. A person with high linguistic-verbal intelligence has the innate ability to understand and use verbal and written languages. This person would do much better with a set of written instructions to assemble their nightstand, even if those instructions didn’t have any pictures.

3 Mathematical intelligence

Mathematical intelligence is more than just the ability to work with numbers. This intelligence is also known as “logical intelligence.” People with this type of intelligence can see connections between different moving parts. They are able to use reasoning and logic to investigate an idea. They are also able to work with more abstract ideas that aren’t necessarily put on paper.

So what if there were no instructions on how to build this nightstand? What if you just had a set of parts and the tools to put the nightstand together? Someone with mathematical intelligence may be able to put these parts together. They might even brainstorm some ways that each part of the nightstand could be used more effectively!

4 Kinesthetic intelligence

Not all problems are solved by looking at a page or listening to instructions. Someone with kinesthetic intelligence has the ability to learn by doing. They are often very skilled in moving their body, including working with their hands. Athletes and tradesmen are likely to have high kinesthetic intelligence.

A person with high kinesthetic intelligence might have a hard time building a nightstand with pictures or written instructions. But if they can have someone who knows how to build the nightstand beside them, they can learn by doing.

5 Musical intelligence

Musical intelligence is the ability to understand and produce music. I’m not just talking about being able to play the piano. A person with high musical intelligence can listen to a song and know what key it’s in. They can hear a note and tell if it’s flat or sharp. They can harmonize with what’s playing on the radio with ease.

As we move into the next few types of intelligence, I want to think a bit out of the box. Sure, a person with high musical intelligence probably also has other types of intelligence that will help them build that nightstand. But they will also excel more in other tasks. Maybe they put together a playlist to keep friends focused as they build nightstands. Maybe they can help write a jingle for the nightstand company to sell more products. Not all tasks appeal to one type of intelligence.

6 Interpersonal intelligence

Interpersonal intelligence is the ability to work with others. People with these abilities can negotiate, persuade, and empathize. They don’t have to know someone personally to understand how they are feeling or see their perspective.

If a person with high interpersonal intelligence didn’t want to build a nightstand, they could easily convince someone to do it for them. They could also sell the nightstand with ease!

7 Intrapersonal intelligence

Intrapersonal intelligence is the ability to understand oneself. Rather than empathizing with others, a person with high intrapersonal intelligence can tap into their own feelings with ease and understand their motivations. It is easy for this person to make achievable goals, take breaks when they need to, and manage their feelings.

Where does the nightstand fit in here? Well, a person with intrapersonal intelligence may be able to assess whether they can build this nightstand in the first place. They know their skills and they know if they have the time or capacity to get this (and other) projects done. If they know that this project will just frustrate them or be a waste of time, they will find another solution and go about their day.

8 Naturalistic intelligence

Naturalistic intelligence doesn’t involve the human world at all. A person with this intelligence has the ability to understand and interact with the natural world. They feel comfortable with plants, animals, and the relationship between these beings and humans.

Like musical intelligence, naturalistic intelligence doesn’t really apply to building a nightstand. But someone with this type of intelligence is more likely to be aware of the materials used to build the nightstand. They might have a lot of plants ready to put on the nightstand once it is built. This person may rely on other types of intelligence to build the nightstand, but once the task is over, they can go back to more interesting tasks and projects.

9 Existential intelligence

This final type of intelligence was added to Gardner’s list years after he published his original theory. Existential intelligence is the ability to dig deeper and contemplate the human condition. A person with this type of intelligence uses metacognition or inner wisdom to contemplate life’s big questions. Again, a person with this type of intelligence may rely on other skills to build a nightstand. Their skills are better suited as a religious leader, philosopher, or other profession that wants to put together “the big picture.”

Take Advantage of Your Intelligence

Gardner says that “there is now a massive amount of evidence from all realms of science that unless individuals take a very active role in what it is that they're studying, unless they learn to ask questions, to do things hands-on, to essentially recreate things in their own mind and then transform them as is needed, the ideas just disappear.” If you want to truly learn something, it’s not enough to sit in a classroom and let a professor’s lecture go in one ear and out the other. You need to harness your intelligence to learn the things you want to learn. Your approach may look different from your classmate’s, your parent’s, or your friend’s. But that’s okay. What matters is that you continue learning and growing, even if it’s in a rather unique way.

Howard Gardner’s 9 Types of Intelligence (Examples)

Are you intelligent?

The answer to that might be more complicated than you think. Many people can say “yes” and they can say “no” at the same time!

Why? Because there isn’t just one way to be intelligent. Some, like Harvard psychologist Howard Gardner, say that there are nine types of intelligence. His work is a response to earlier theories of intelligence, that suggested that there was just one type of general intelligence.

What Are The Nine Types of Intelligence?

- Visual-spatial intelligence

- Linguistic-verbal intelligence

- Mathematical intelligence

- Kinesthetic intelligence

- Musical intelligence

- Interpersonal intelligence

- Intrapersonal intelligence

- Naturalistic intelligence

- Existential intelligence

Visual-spatial intelligence

Visual-spatial intelligence is the ability to create, understand, or process visual information. If you’ve ever met someone who can look at a blueprint and design a whole room, you can guess that they have high visual-spatial intelligence.

Here’s an example of when this comes in handy. You get a new nightstand - but you have to assemble it. When you open up the assembly instructions, you don’t see any words. Just pictures! If you have high visual-spatial intelligence, this won’t be a problem. You’ll still be able to put together that nightstand.

Linguistic-verbal intelligence

If you have high linguistic-verbal intelligence, those instructions probably wouldn’t get you too far. A person with high linguistic-verbal intelligence has the innate ability to understand and use verbal and written languages. This person would do much better with a set of written instructions to assemble their nightstand, even if those instructions didn’t have any pictures.

Mathematical intelligence

Mathematical intelligence is more than just the ability to work with numbers. This intelligence is also known as “logical intelligence.” People with this type of intelligence can see connections between different moving parts. They are able to use reasoning and logic to investigate an idea. They are also able to work with more abstract ideas that aren’t necessarily put on paper.

So what if there were no instructions on how to build this nightstand? What if you just had a set of parts and the tools to put the nightstand together? Someone with mathematical intelligence may be able to put these parts together. They might even brainstorm some ways that each part of the nightstand could be used more effectively!

Kinesthetic intelligence

Not all problems are solved by looking at a page or listening to instructions. Someone with kinesthetic intelligence has the ability to learn by doing. They are often very skilled in moving their body, including working with their hands. Athletes and tradesmen are likely to have high kinesthetic intelligence.

A person with high kinesthetic intelligence might have a hard time building a nightstand with pictures or written instructions. But if they can have someone who knows how to build the nightstand beside them, they can learn by doing.

Musical intelligence

Musical intelligence is the ability to understand and produce music. I’m not just talking about being able to play the piano. A person with high musical intelligence can listen to a song and know what key it’s in. They can hear a note and tell if it’s flat or sharp. They can harmonize with what’s playing on the radio with ease.

As we move into the next few types of intelligence, I want to think a bit out of the box. Sure, a person with high musical intelligence probably also has other types of intelligence that will help them build that nightstand. But they will also excel more in other tasks. Maybe they put together a playlist to keep friends focused as they build nightstands. Maybe they can help write a jingle for the nightstand company to sell more products. Not all tasks appeal to one type of intelligence.

Interpersonal intelligence

Interpersonal intelligence is the ability to work with others. People with these abilities can negotiate, persuade, and empathize. They don’t have to know someone personally to understand how they are feeling or see their perspective.

If a person with high interpersonal intelligence didn’t want to build a nightstand, they could easily convince someone to do it for them. They could also sell the nightstand with ease!

Intrapersonal intelligence

Intrapersonal intelligence is the ability to understand oneself. Rather than empathizing with others, a person with high intrapersonal intelligence can tap into their own feelings with ease and understand their motivations. It is easy for this person to make achievable goals, take breaks when they need to, and manage their feelings.

Where does the nightstand fit in here? Well, a person with intrapersonal intelligence may be able to assess whether they can build this nightstand in the first place. They know their skills and they know if they have the time or capacity to get this (and other) projects done. If they know that this project will just frustrate them or be a waste of time, they will find another solution and go about their day.

Naturalistic intelligence

Naturalistic intelligence doesn’t involve the human world at all. A person with this intelligence has the ability to understand and interact with the natural world. They feel comfortable with plants, animals, and the relationship between these beings and humans.

Like musical intelligence, naturalistic intelligence doesn’t really apply to building a nightstand. But someone with this type of intelligence is more likely to be aware of the materials used to build the nightstand. They might have a lot of plants ready to put on the nightstand once it is built. This person may rely on other types of intelligence to build the nightstand, but once the task is over, they can go back to more interesting tasks and projects.

(theory of multiple intelligences):-

Existential intelligence

This final type of intelligence was added to Gardner’s list years after he published his original theory. Existential intelligence is the ability to dig deeper and contemplate the human condition. A person with this type of intelligence uses metacognition¹ or inner wisdom to contemplate life’s big questions. Again, a person with this type of intelligence may rely on other skills to build a nightstand. Their skills are better suited as a religious leader, philosopher, or other profession that wants to put together “the big picture.”

Take Advantage of Your Intelligence

Gardner says that “there is now a massive amount of evidence from all realms of science that unless individuals take a very active role in what it is that they're studying, unless they learn to ask questions, to do things hands-on, to essentially recreate things in their own mind and then transform them as is needed, the ideas just disappear.” If you want to truly learn something, it’s not enough to sit in a classroom and let a professor’s lecture go in one ear and out the other. You need to harness your intelligence to learn the things you want to learn. Your approach may look different from your classmate’s, your parent’s, or your friend’s. But that’s okay. What matters is that you continue learning and growing, even if it’s in a rather unique way.

1997 interview with Harvard University Professor Howard Gardner about new forms of assessment and multiple intelligences.

View transcript

Big Thinkers: Howard Gardner on Multiple Intelligences (Transcript)

Howard Gardner: We have schools because we hope that someday when children have left schools that they will still be able to use what it is that they’ve learned. And there is now a massive amount of evidence from all realms of science that unless individuals take a very active role in what it is that they’re studying, unless they learn to ask questions, to do things hands-on, to essentially recreate things in their own mind and then transform them as is needed, the ideas just disappear.

The student may have a good grade on the exam. We may think that he or she is learning, but a year or two later there’s nothing left. If, on the other hand, somebody has carried out an experiment himself or herself, analyzed the data, made a prediction and saw whether it came out correctly; if somebody is doing history and actually does some interviewing himself or herself, oral histories, then reads the documents, listens to it, go back and asks further questions, writes up a paper– that’s the kind of thing that’s going to adhere, where if you simply memorize a bunch of names and a bunch of facts and a bunch of– even a bunch of definitions, there’s nothing to hold onto.

The idea of multiple intelligences comes out of psychology. It’s a theory that was developed to document the fact that human beings have very different kinds of intellectual strengths and that these strengths are very, very important in how kids learn and how people represent things in their minds, and then how people use them in order to show what it is that they’ve understood. If we all had exactly the same kind of mind and there was only one kind of intelligence, then we could teach everybody the same thing in the same way and assess them in the same way, and that would be fair. But once we realize that people have very different kinds of minds, different kinds of strengths– some people are good in thinking spatially, some people are good in thinking language, other people are very logical, other people need to do hands-on; they need to actually explore actively and to try things out– once we realize that, then education which treats everybody the same way is actually the most unfair education because it picks out one kind of mind, which I call the Law Professor Mind, somebody who’s very linguistic and logical, and says, “If you think like that, great. If you don’t think like that, there’s no room in the train for you.” If we know that one child has a very spatial– a visual or spatial way of learning, another child has a very hands-on way of learning, a third child likes to ask deep philosophical questions, a fourth child likes stories, we don’t have to talk very fast as a teacher. We can actually provide software, we can provide materials, we can provide resources which present material to a child in a way in which the child will find interesting and will be able to use his or her intelligences productivity, and to the extent that the technology is interactive, the child will actually be able to show his or her understanding in a way that’s comfortable to the child.

We have this myth that the only way to learn something is read it in a textbook or hear a lecture on it, and the only way to show that we’ve understood something is to take a short-answer test or maybe occasionally with an essay question thrown in. But that’s nonsense. Everything can be taught in more than one way, and anything that’s understood can be shown in more than one way. I don’t believe because there are eight intelligences we have to teach things eight ways. I think that’s silly. But we always ought to be asking to ourselves, “Are we reaching every child, and if not, are there other ways in which we can do it?” I think that we teach way too many subjects and we cover way too much material, and the end result is that students have a very superficial knowledge– as we often say, a mile wide and an inch deep– and then once they leave school, almost everything’s been forgotten. And I think that school needs to change to have a few priorities and to really go into those priorities very deeply.

So let’s take the area of science. I actually don’t care if a child studies physics or biology or geology or astronomy before he goes to college. There’s plenty of time to do that kind of detailed work. I think what’s really important is to begin to learn to think scientifically, to understand what a hypothesis is, how to test it out and see whether it’s working or not; if it’s not working, how to revise your theory about things. That takes time. There’s no way you can present that in a week or indeed even in a month. You have to learn about it from doing many different kinds of experiments, seeing when the results are like what you predicted, seeing when they’re different, and so on. But if you really focus on science in that kind of way, by the time you go to college– or, if you don’t go to college, by the time you go to workplace– you’ll know the difference between a statement which is simply a matter of opinion or prejudice, and one for which there’s solid evidence.

The most important thing about assessment is knowing what it is that you should be able to do. And the best way for me to think about it is a child learning a sport or a child learning an art form, because they’re as completely un-mysterious– what you have to be to be a quarterback or a figure skater or a violin player. You see it, you try it out, you’re coached. You know when you’re getting better. You know how you’re doing compared to other kids. In school, assessment is mystifying. Nobody knows what’s going to be on the test, and when the test results go back, neither the teacher nor the student knows what to do.

So what I favor is highlighting for kids from the day they walk into school what are the performances and what are the exhibitions for which they’re going to be accountable. Let’s get real. Let’s look at the kinds of things that we really value in the world. Let’s be as explicit as we can. Let’s provide feedback to kids from as early as possible, and then let them internalize the feedback so they themselves can say what’s going well, what’s not going so well.

I’m a writer, and initially I had to have a lot of feedback from editors, including a lot of rejections. But over time, I learned what was important, I learned to edit myself, and now the feedback from editors is much less necessary. And I think anybody as an adult knows that as you get to be more expert in things you don’t have to do so much external critiquing; you can do what we call self-assessment. And in school, assessment shouldn’t be something that’s done to you. It should be something where you are the most active agent.

I think for there to be longstanding change in American education– that is widespread rather than just on the margins– first of all people have to see examples of places which are like their own places where the new kind of education really works, where students are learning deeply, where they can exhibit their knowledge publicly, and where everybody who looks at the kids says, “That’s the kind of kids I want to have.” So we need to have enough good examples.

Second of all, we need to have the individuals who are involved in education, primarily teachers and administrators, believe in this, really want to do it, and get the kind of help that they need in order to be able to switch, so to speak, from a teacher-centered, “Let’s stuff it into the kid’s mind” kind of education, to one where the preparation is behind the scenes and the child himself or herself is at the center of learning.

Third of all, I think we need to have assessment schemes which really convince everybody that this kind of education is working. It does no good to have child-centered learning and then have the same old multiple choice tests which were used 50 or 100 years ago.

Finally, I think there has to be a political commitment which says that this is the kind of education which we want to have in our country, and maybe outside this country, for the foreseeable future. And as long as people are busy bashing teachers or saying that we can’t try anything new because it might fail, then reform will be stifled as it has been in the past.

Howard Gardner is the John H. and Elisabeth A. Hobbs Professor in Cognition and Education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. He also holds positions as adjunct professor of psychology at Harvard University and Senior Director of Harvard Project Zero.

He has written twenty books, hundreds of articles, and is best known for his theory of multiple intelligences, which holds that intelligence goes far beyond the traditional verbal and linguistic and logical and mathematical measurements. Here he discusses student-directed learning, multiple intelligences, and a different approach to assessment.

This interview was conducted in 1997. To learn more, please see this 2018 article on some common misunderstandings about multiple intelligences theory and learning styles.

Watch YouTube here

Early Childhood Education

Introducing Metacognition in Preschool

By modeling self-talk and providing choices, teachers can encourage young children to think about their thinking.

No comments:

Post a Comment