TABLE OF CONTENTS

"EXERCISE IS MOVEMENT, BUT MOVEMENT IS NOT EXERCISE." - KATY BOWMAN.

Episode 76 – Katy Bowman – On Movement and Community, Social Media Breaks and Moving Parties.

Katy Bowman joins the podcast for the second time to talk expand the conversation we had in 2016. (Find that episode here – Episode 28) This time we talk about the intersection of movement and community, her summer social media break, and how to have a moving holiday party. Bowman is a biomechanist who spends her time researching and sharing with the world the role movement plays in our bodies and in the world.

Her work is known worldwide and she has been featured on podcasts like Joe Rogan Experience, Primal Blueprint, Robb Wolfe and many others. She blends scientific approach with straight talk about sensible, whole-life movement solutions, her website, and award-winning podcast, Katy Says, reach hundreds of thousands of people every month, and thousands have taken her live classes.

Her books, the bestselling Move Your DNA (2014) recently expanded and updated, Diastasis Recti (2016), Don’t Just Sit There (2015), Whole Body Barefoot (2015), Alignment Matters (2013), Every Woman’s Guide to Foot Pain Relief (2011), Movement Matters (2016), and Dynamic Aging (2016) have been critically acclaimed and translated worldwide.

Passionate about human movement outside of exercise, Katy volunteers her time to support the larger reintegration of movement into human lives by providing movement courses across widely varying demographics and working with non-profits promoting nature education. She also directs and teaches at the Nutritious Movement Center Northwest in Washington state, travels the globe to teach Nutritious Movement™ courses in person, and spends as much time outside as possible with her husband and children.

We talk about her social media break in the episode. To hear more about her break check out her episodes of Katy Says dedicated to the nitty-gritty of getting offline.

Enjoy this episode with Katy Bowman and hope you find movement while listening.

Facebook: www.facebook.com/nutritiousmovement

Twitter: https://twitter.com/NutritiousMvmnt

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/nutritiousmovement/

Chapter 2: Balance, Stability, and Getting Over the Fear of Falling

Chapter 3: Super-Strong Hips and Single-Legged Balance

Chapter 4: Walking

Chapter 5: Reaching, Carrying, Lifting, and Other Functional Movements

Chapter 6: Fit to Drive

Chapter 7: Movement Is Part of Life

GET MOVING

All-Day Alignment Checks

Tips for Moving More in Daily Life

Whole-Body Mobility Flow

Exercise Glossary

Appendix: Exercise Equipment and Additional Sources of Information

References

Index

Acknowledgments

About the Authors

INTRODUCTIONS

When I was a kid, my mother observed that I “always insisted on learning the hard way,” meaning that I wouldn’t let myself benefit from the wisdom of others, and needed, instead, to experience lessons for myself. Fortunately, I’ve grown out of this trait in many respects. Now when I meet people who have had the experience of walking down a path I am currently on, I value their insight. And what I’ve learned from the people around me who’ve lived much longer than I have is that I need to take good care of my body, because if I don’t, I’ll miss being able to move how I want to.

I have had my body for only forty-one years, but over the last twenty-two, I’ve had the pleasure of working one-on-one with over a thousand bodies, most of them older than mine. And if there is one message I’ve received loud and clear, it’s that those coming to me for corrective exercise and alignment work in their sixties and seventies wish they had had access to this material in their twenties. From these people, I’ve learned to value future physical function now. That’s why I’ve chosen to write this book. DYNAMIC AGING.

I teach people new ways to move their bodies. And I’ve had the good fortune of working with a large group of people over a long period of time. This means I have been exposed to a lot of data—about what people have done in the past, which hobbies and injuries they have, and where they are today.

I’ve worked with groups of competitive athletes, young children, pregnant mamas, post-natal mamas, and breast cancer survivors. I’ve led courses for those with cardiovascular disease, bad backs, and pelvic floor disorders, and thousands of people suffering with foot pain. I’ve gathered the information on what thousands of people have done in their past, and as a result, I’ve become familiar with the average movement history of today’s seventy- and eighty-year-olds in my culture.

This book includes the stories of four of my clients: an attorney, a dance-movement therapist and RN, a teacher and social worker, and a sassy, kick-ass graphic artist (she’s done most of the graphics in this book) who travels to far away countries. These women began working with me in their late sixties and early seventies and were part of a large group that started taking classes in my new-at-the-time exercise facility around a decade ago. They were the four who continued to show up, sometimes two hours a day Monday through Friday, for years, eventually studying to become movement teachers themselves.

Now, in their mid- to late seventies at time of writing (with one turning eighty just as this book is being published), they are some of the few of their own peer group who haven’t made a transition into senior living centers. They look younger now than they did years ago. They move “younger” than they did years ago. I regularly tell people this is possible—that they can look, move, and feel younger through smart movement and regular training—but I’m forty-one years old. Who’s going to believe me when I say that starting at sixty or even seventy isn’t too late and that tremendous improvement is possible? And so I thought I would ask Joan, Lora, Joyce, and Shelah to share with you their own insights about how a goldener can turn back the clock. You’ll see their commentary throughout the book, the perspectives of four strong, dedicated, powerful women well into their seventies who are active and thriving.

But what is a goldener? When these women came to me with the idea for this book, they were clear: We don’t want “old” in the title. Or “senior.” Or “geriatric,” for that matter. How about an all-new, beautiful term that describes how we feel about this stage of our lives, the golden age? How about “goldener”? I agree wholeheartedly with their thoughtful word choices, and science seems to as well.

Exercise has powerful capabilities to improve health, but so do words. During a game of charades, have you ever mimed a senior, shuffling at a snail’s pace, stooped over, one hand on the low back and the other on an imaginary cane? As biological beings, our behavioral patterns are shaped by what we see—how our own parents move, how our peers move. Even how cultural norms are portrayed on TV can shape our reality. The question is, how do other people move, and how do preconceived notions of the way the “over sixties” move affect how we move once we, ourselves, are older?

In a study created to measure the impact of positive or negative stereotype reinforcement, researchers found that walking speed and time spent in the balance phase of walking increased after only thirty minutes of intervention (Hausdorff, Levy, and Wei 1999). Did the researchers hand out a magical exercise or stretch? Nope. During a thirty-minute video game, subliminal terms were flashed on the screen: senile, dependent, diseased for one group and wise, astute, accomplished for the other. With absolutely no exercise intervention, the positively reinforced group was able to make gait and walking speed improvements more commonly found after weeks or even months of exercise training. So here’s the takeaway message for everyone: Words can be profound, so practice positive speak about yourself and those around you. And here’s the takeaway message for exercisers: The way you’re moving (or not) right now could be influenced by things other than your physiology.

There are many headlines, some of them about research, announcing the norms of the human experience. However, using age as a variable in research can be problematic as it’s hard to separate age from length of habit. There is a difference between the statements “Older adults are more prone to bunions” and “Older adults who’ve been wearing too-tight shoes for longer are more prone to bunions.” Age is typically selected as a research variable because it is objective and easier to quantify than your behavior over time. You can tell me with great accuracy how old you are, but it’s less likely you could tell me with great accuracy just how many hours you’ve spent with your toes crammed together in your shoes. And so, it is often through language in general and language used in research that we perpetuate the idea that bodies start falling apart simply because they’ve reached a certain age. Of course, all cells will eventually cease to replace themselves, but what’s important here is not the inevitability of decline, but that we’re able to see the difference between natural decline and the loss of function we’re experiencing simply due to weaknesses created by poor movement habits.

And here’s something else to consider: There seems to be a culture-wide decrease in strength that’s not related to age, but to a lifestyle that requires very little movement. A study comparing the grip strength of millennials (those born between approximately 1980 and 2000) in 2015 to the grip strength of this same age group in 1985, for example, shows people’s grips are significantly weaker today than they used to be (Fain and Weatherford 2016). Kids today (I never thought I’d type those words) move less than I did as a kid, and according to my grandparents, I moved less throughout my childhood than they did throughout theirs. Given the human timeline, i.e., the recent introduction of technology and the relatively recent Industrial Revolution, I’ll suggest that with each generation comes less movement. This is actually good news, as it means our perception of the general decline in body weakness over time could very well be coming from the fact that we’ve really just been extremely sedentary the bulk of our lives. We’re mostly under-moved, and not at all too old.

Dynamic Aging is a guide to get you moving more and moving more of you. This isn’t a book that suggests, “Hey, you should start walking!” Instead, it helps you see which parts of your body you can start moving a tiny bit here and there so you feel like going out to take a walk. This guide contains exercises designed to improve your movement habits through simple postural adjustments and exercises designed to challenge your body, gently, in a way that you probably stopped doing a long time ago without realizing it. As you slowly introduce more movement into your life, it’s likely you’ll see an improvement in those movement declines that you had associated with age but that were actually a product of your long-term movement patterns.

This is a guide facilitated by four of the most amazing, dynamic goldeners I know, who began just as you are about to now (with their feet). I hope you will gain as much from reading their experiences as I have from participating in them.

MEET THE GOLDENERS:

Joan

At the age of seventy-one, after a long career as an attorney, I was referred to Katy Bowman for exercises to help with my pelvic prolapse, chronic constipation, and foot problems. I met with her for a whole-body evaluation and began the movement practice that day which would change my life. I am now seventy-eight years of age. My chronic constipation completely disappeared three years into my movement practice. I walk daily and am able to continue to pursue my passion for hiking (three to ten miles), now in FiveFinger and zero-drop shoes, on the mountainous terrain of the trails on our ranch, on the sandy beaches of our nearby coast, and in our quest to hike all of the national parks (thirty-two to date, with the latest six hiked last summer in my seventy-ninth year). I can walk barefoot without discomfort. I climb and hang from trees in our forest—something I would never have thought of doing but for Katy’s example and instruction. At seventy, I was scheduled for major surgery to address my pelvic organ prolapse. The surgery has not yet been necessary. My balance is the best it has ever been—about two years ago I walked barefoot across a log six feet above a rushing river, something I never thought I’d be able to do, and certainly not for the first time at age seventy-seven. That same year (2015), Joyce (then seventy-eight) and I walked the sands of the Dungeness Spit in Washington for a total of eleven miles to see the lighthouse. And my overall body strength has improved significantly.

Changing how I move has changed my life, and I now work as a movement teacher, sharing what I’ve learned with others.

Joyce

I sustained painful knee injuries twenty-nine years ago. I had completed my teaching career of twenty years and was in the process of getting my master’s degree in social work when I injured the meniscus of my right knee doing yoga practice at home without the proper warm-up needed because of a studying, sitting, listening overload. The injuries I sustained—a meniscus torn in one knee and the other damaged shortly after from compensating stresses—are common. For years I sought relief from the pain and restricted mobility with a variety of palliative measures: limited walking, Tai Chi, gentle yoga stretching, daily pain pills, weekly chiropractic treatments, and massage therapy. Yet other than surgery—a choice I was unwilling to make due to the risk of complications and limited chance for sustained improvement—there appeared to be no path for healing and wellness. That all changed for me when I was sixty-nine, and my chiropractor told me she would not continue to treat me unless I learned how to strengthen my muscles to keep the bones adjusted between our appointments. I did not want to lose my chiropractor, so when a friend told me about Katy Bowman’s movement classes, I went. Almost immediately I began to understand my body from a biomechanical point of view. I learned that injuries, pain, and inflammation are our bodies’ warning flags: we shouldn’t ignore them or power through them, but rather teach ourselves to heal using them as our guides. This whole-body model of wellness has taught me that our health is influenced more by our habits—the way we use, load, and live in our body—than by our age. Today at age seventy-nine (I’ll be eighty when this book is printed), without having had any surgery, I have regained my ability to walk without pain or impairment and to live with wellness in my body, mind, and spirit. Whole-body movement has made this possible in my life and I feel strong and capable walking the path to healing and wellness.

Lora

At sixty-eight, I was scheduled for the first of at least two surgeries that would have left me with a complete knee replacement. Through my work as an RN and dance-movement therapist, I thought I knew and had experienced all the self-help modalities and was resigned to “the knife.” A friend talked me into trying Katy’s exercise program. Although convinced that it was another incomplete answer, I decided I should try everything. And her program turned out to be just that: everything. I had endured restless leg syndrome since my teens (before it had a name). For six decades I lost an average of one night’s sleep every two weeks to nerve pain originating in my sacrum. After doing some of her exercises for two weeks, I began noticing that I wasn’t even getting twinges of my usual “restless leg.” That was an amazing finding for me, as I’d thought it was a familial malady. This success empowered me to cancel knee surgery and more frequently try gentle knee-stretching exercises for my frozen knee. Currently, at seventy-five, I can walk up to six miles on any terrain, and walk to all my in-town errands and appointments on my original biological equipment.

More important to me even than that was my ability to pack into the Sierra Mountains. Last year, I was able to join my sons and some grandkids on a one-week, lake-to-lake adventure. I carried one-fifth of my weight in supplies over beautiful but sometimes rugged and steep terrain. I started out early each day and was the last to arrive at the next camp, but I still feel both lucky and triumphant. Incorporating the principles in this book into my daily activities has created opportunities to change life-long conditions I thought were “just me.” My biggest reward, however, is the excitement of students who, like me, are finding that aging isn’t bad after all—aging is an opportunity to move, play, and expand into new areas.

Shelah

I started classes with Katy at age sixty-six, when I retired from my job as a graphic designer (sitting at a computer a lot). I’m a life-long exerciser, but I was so impressed with the logic of the scientific theory of her program, I decided to do more than the exercises—I decided to take her teacher training program.

I’m a work in progress and a product of my long-term habits. While preparing for a trip just before my seventy-fifth birthday, I reached into my closet trying to find a garment and twisted too far (not a Katy-recommended movement, for sure), and the resulting back pain made it obvious something was very wrong. Because I wanted to go on my trip, I treated the pain aggressively (bad move) and finally went to my family doctor. An MRI showed serious scoliosis in my back accompanied by painful shearing of lumbar vertebrae.

After a very long month of doctor-prescribed inactivity except five- to ten-minute walks on level ground, I was well enough to start the basic exercises you’ll be learning in this book. Today at seventy-eight I can walk three to four miles daily in relative comfort. Healing at this stage of my life often takes a long time and, yes, it has tried my patience. Using the principles and exercises outlined here, my back is healing and I am slowly regaining my active lifestyle.

Moving better doesn’t automatically mean you don’t get injured, but it makes you more resilient if you do. Katy’s teaching has given me the knowledge and tools to know what movements I can do, like hanging and core strengthening, and which movements I must be very careful doing—like twisting.

Note From the Goldeners

This book is for readers of any age. Attaining and maintaining mobility, strength, and balance is a lifetime task. When we were young, we learned to balance, optimize our stability, stay on our feet for extended periods of time, and walk upright with confidence. Then, our lives took us in a more sedentary direction until, lo and behold, we found that easy movement had been lost somewhere along the way. We have learned so many exercises through our training with Katy, but the exercises in this book are those that we feel have been key to regaining and maintaining the balance and mobility lost to us through years of neglect.

Katy will be giving the more technical information and guidelines throughout this book, but this is what we septuagenarians have found helpful to keep in mind:

• Work to incorporate the basic alignment points and movements into your daily routine.

• Treat your body with appreciation and respect.

• Approach exercise with mindfulness, not force.

• Remember even small changes add up to larger functional improvements.

One job of your muscles is to stabilize your joints to allow full function of your entire musculoskeletal system. The exercises in this book are designed to mobilize and strengthen neglected muscles for the purpose of improving your head-to-toe alignment and day-today function.

SAFETY FIRST. It is always important to check with your doctor or physical therapist before beginning any exercise program, especially if you have “replacement” parts, including but not limited to hip replacements or knee replacements.

DISTINGUISH BETWEEN PAIN AND NEW SENSATIONS. If you experience pain while doing an exercise, try other options or modifications offered or come back in a few days, and try it again. You are the boss of you! Take responsibility for your own safety and well-being.

CRAMPING may occur when muscles are being stretched or used in different ways. If you experience cramping during an exercise, you may STOP doing the exercise and allow the muscles to relax before doing it again.

SORENESS after exercise may occur as a result of using muscles (and joints, bones, and fascia) in a new way and/or overusing your tissue (going too far too fast). Be gentle with yourself as you try these exercises. Go slowly, focus on what you are doing, and be mindful of what your body is experiencing. Adjust accordingly.

SAFETY TIP: For added stability while doing any standing evaluation or exercise, we recommend you start by holding on to or leaning against a secure surface such as a counter, the back of a sofa, a wall, or a closed door to prevent falling. While the overall goal is to do these exercises without support, safety and prudence should always be primary concerns.

SUGGESTED EQUIPMENT

• Thick and heavy book or yoga block

• Chair with straight back and level seat

• Rolled up towel or half foam roller (pictured below)

• Tennis ball

• Full-length mirror (very useful but not mandatory)

• Mat (optional)

HALF FOAM ROLLER

Who Can Use this Book?

A book on dynamic aging is really for anyone, at any age. Truly, exercise programs should be geared to strength and skill levels rather than to any particular age, which can have little relevance to strength and skill levels, as you’re about to find out. And so, this book could be easily utilized by anyone wanting to be more dynamic but feeling like they’re starting from a place of little balance and strength.

CHAPTER 1

YOUR FEET ARE YOUR

FOUNDATION

I love feet. In fact, I’ve written two whole books about them (Simple Steps to Foot Pain Relief and Whole Body Barefoot). You should love your feet too. Not only are they amazingly complex—they each have thirty-three joints and over a hundred muscles, tendons, and ligaments—but they also serve as the foundation to almost every day-to-day task you perform. This is why stiff, painful, under-moved feet are the first body part you should start moving better if you’re finding your other parts—like knees and hips—difficult to move.

Even though most of what we do with our bodies—get up out of a chair, take a walk through the park, drive a car—requires we use our feet to a certain degree, we never really use the sophisticated machinery of our feet to their full potential. Instead, we use all of the many parts that make up our feet as one clump—one clump living inside of a shoe.

Chances are that you (like me until a few years ago, and probably also like almost everyone else you know) have spent the bulk of your life wearing “good” shoes. Stiff shoes. Supportive shoes. Shoes with elevated heels and limited space to stretch your toes. Shoes that, over decades, have sort of “casted” the muscles in your feet. This, combined with our excessive sitting and lack of walking on natural terrain (and many other habits we have), can lead to foot ailments such as bunions, hammertoes, bone spurs, plantar fasciitis, osteoarthritis, and neuropathy. If you don’t move all of the joints and muscles in your feet, then your

circulation decreases, which has big implications for your ability to heal from injuries, especially important to those dealing with diabetes. Our immobilized feet can also lead to ailments that don’t seem immediately foot related—knee, hip, lower-back, and even neck pain can all be connected to your foot health.

Perhaps you’ve experienced so much pain that you’ve been prescribed special shoes or splints or orthotics; maybe you even have to limit your walking because of pain you’ve experienced.

But here’s the good news: It’s much more likely that your feet feel weak and stiff because you’ve spent a lifetime not using the muscles within them than it is your feet are weak and stiff solely due to their age.

Joan Says

Joan Says

I was always a barefoot girl. When I got into my forties, I began to notice pain in the balls of my feet when walking on a hard surface like a hardwood, tile, or concrete floor. Then I began noticing I could not walk barefoot at the beach without the balls of my feet hurting. I had never worn really high heels—nothing more than two inches. I was surprised and dismayed. I was prescribed orthotics for my dressy work shoes AND for my sporty tennis shoes. I had to wear them in just about every shoe I owned. However, there didn’t seem to be orthotics for heels. This created even more discomfort, because all my weight was being shoved down on the balls of my feet. I experienced pain when walking and standing and I got backaches. Whenever I could, I would slip off my shoes at work while sitting at my desk. And I wanted to sit a lot more of the time.

When I “retired” (left my lawyering days), I did a lot more Olympic-style race-walking and was paying well over $l00 a pair for walking shoes that were engineered with air or other devices supposedly to protect my feet from feeling any pain. However, training for half marathons was not possible without orthotics. I finally resigned myself to the fact that I would wear orthotics for the rest of my life because I knew I wasn’t getting any younger. And we all know it’s all downhill physically as you get older (or so I had heard).

When I met with Katy for my first movement session, she explained the importance of getting my weight off the front of my feet and back onto my heels. For me this was a HUGE challenge because for nearly seventy years I had been standing with my pelvis forward, knees slightly bent, and weight on the balls of my feet. (It was if I had a magnet in my belly that was constantly being pulled toward my kitchen counter when I was washing dishes or preparing food.) She suggested I try reducing the height of my heel, cautioning me to start out wearing flat shoes for only a short time at first to allow my feet and body to adjust to having my weight more on the rear of my foot. But I couldn’t get the lower shoes to fit properly with my orthotics. She suggested I try my new shoes, along with my new exercises and foot mobility, without my orthotics. I was apprehensive but figured it would be self-limiting—if it hurt too much, I could just go back to my old shoes and orthotics.

Here we are, eight years later, and I’ve never gone back. Not only have I found it unnecessary to use my old whole-foot orthotics, I can again walk barefoot on the beach and for limited periods on the tile surfaces at home. Unfortunately, I have discovered the fat pads of the bottoms of my feet have either moved or disappeared, leaving my bones without cushions, so in my zero-drop and “barefoot” FiveFinger shoes, I now use a small, soft metatarsal pad and thin, flat liner pad cut just behind my toes to pad just under the soles of my feet. With this arrangement I hike three to five miles regularly on dirt trails, and do longer hikes in the nearby mountains and in the national parks. So not only has the condition of my feet improved, I am now doing something I never did before—using minimal shoes to improve my overall whole-body conditioning.

The longer we’ve been inactive, the less all our parts move, and the more we start doing things in our life that repeat the cycle. For example, sitting for long portions of each day for school and then work may have left the muscles in your legs weak, the joints in your knees and hips tight. When putting on a shoe every morning becomes a challenge—which is really another way of saying that moving in a particular way has become a challenge—we start opting for shoes that are easier to put on.

Shoes that require less hip and knee use are typically slip-ons, shoes that you can just poke your feet into. But here’s the thing: Slip-on shoes could just as easily be called slip-OFF shoes, which is why, when you wear them, you have to clench your toes and stiffen the muscles in your feet and ankles just to keep them on. Stiff feet are weak feet—feet that aren’t able to spread out into a wider, more stable base while you’re walking and can’t sense your environment and respond quickly.

While slippers and slide-on shoes are certainly a convenient way to address one consequence of stiff hips (i.e., difficulty putting on shoes), a “big picture” approach would be to work toward better hip mobility so that you don’t end up adding “tight feet” and “decreased balance” to what started as just a hip issue (see pages 182–183 for an exercise to address this).]]

The following exercises are truly foundational in that they are designed to strengthen and mobilize the feet to improve their function and how they feel, but also in that larger movements and skills, like balance and walking, depend on well-functioning feet. We’re used to approaching our health in segments. Foot exercises are for the feet, hip stretches benefit the hips, and balance exercises are to improve balance. While this is true, exercises for the feet can also benefit the hips and balance. The effects of movement are holistic in nature, so if you’re thinking “my feet are fine, I want to jump to balance challenges,” know that each exercise in this book directly impacts all other movements you’d like your body to be able to do, and starting with the feet can make a huge impact because, as I’ve already mentioned, most other things you do with your body begin at the feet.

Case in point, the first exercise for your feet isn’t even a movement of the feet themselves: it’s a movement of your hips.

WEAR YOUR HIPS OVER YOUR HEELS

Most of us have been wearing shoes with a heel. It doesn’t matter if it’s one inch or three, conventional shoes all come with raised heels and that has forced many of us to shift our pelves forward to balance out the downhill slope we’ve strapped to our feet. Line your hips up over your ankles.

[[Barefoot-Friendly Floor Space

One of the reasons thick soles are recommended is because many of us have lost the ability to sense things with our feet, and may inadvertently step on something sharp enough to harm them. However, that puts us in a pickle—in order to redevelop our feet’s sense, we need to go unshod and make them healthier, which then puts our feet at risk. The solution is to create a barefoot-friendly floor space.

• Vacuum an area you want to keep clear to make sure you don’t step on any sharp debris (think pins, needles, etc.).

• For an extra layer of protection, roll out a thick towel or yoga mat over the area you’ve vacuumed.

• If your feet are very sensitive, double up on floor coverings—put a mat over a carpet, or layer a blanket or many towels for cushioning.

• Any time you’re going to your barefoot space, do another visual check for any items you don’t want to step on.]]

TOP OF THE FOOT STRETCH

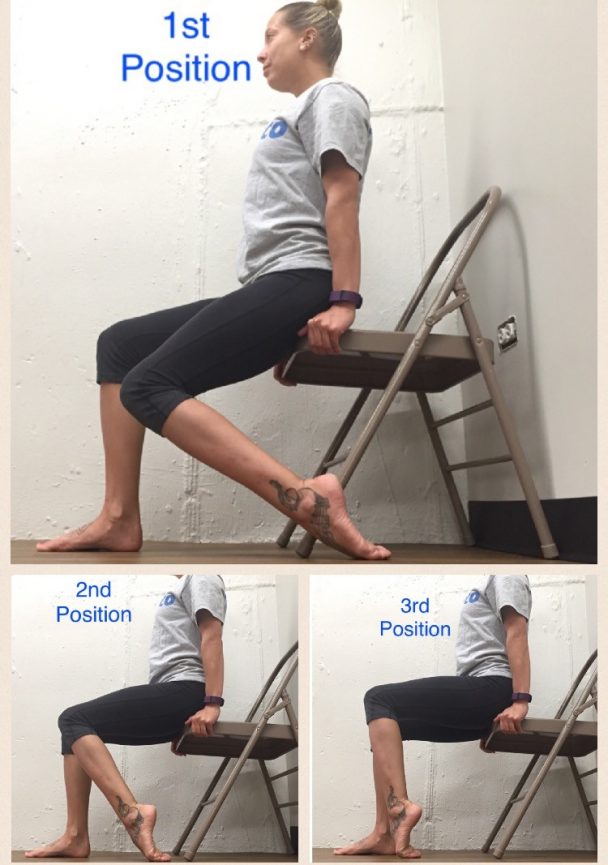

The Top of the Foot Stretch stretches the muscles of your toes, feet, and ankles all at once, and targets any muscle clumps that might have developed due to too-tight shoes or postural habits. This stretch is key to improving toe, foot, and ankle mobility.

Begin by sitting near the front edge of a chair, feet flat on the floor. Reach back with one foot, tucking the toes under. Keep your heel centered; do not let your ankle flop to either side. Do not force the top of the foot to floor in any way; allow your foot to lower as your tissues allow.

Once you can do this stretch with ease, it is time to try it standing up. Holding on to a wall or chair, reach your right foot behind you with the toe under, top of the foot stretching toward the floor. It is common at first to bend your torso slightly forward or shift your hips out in front to reduce the load to the feet. Notice these and try to bring your chest and hips back so they stack over your non-stretching foot. To make the foot stretch less you can always shorten the distance you have reached the leg back or return to the chair to lessen the load.

"EXERCISE IS MOVEMENT, BUT MOVEMENT IS NOT EXERCISE." - KATY BOWMAN.

Episode 76 – Katy Bowman – On Movement and Community, Social Media Breaks and Moving Parties.

Katy Bowman joins the podcast for the second time to talk expand the conversation we had in 2016. (Find that episode here – Episode 28) This time we talk about the intersection of movement and community, her summer social media break, and how to have a moving holiday party. Bowman is a biomechanist who spends her time researching and sharing with the world the role movement plays in our bodies and in the world.

Her work is known worldwide and she has been featured on podcasts like Joe Rogan Experience, Primal Blueprint, Robb Wolfe and many others. She blends scientific approach with straight talk about sensible, whole-life movement solutions, her website, and award-winning podcast, Katy Says, reach hundreds of thousands of people every month, and thousands have taken her live classes.

Her books, the bestselling Move Your DNA (2014) recently expanded and updated, Diastasis Recti (2016), Don’t Just Sit There (2015), Whole Body Barefoot (2015), Alignment Matters (2013), Every Woman’s Guide to Foot Pain Relief (2011), Movement Matters (2016), and Dynamic Aging (2016) have been critically acclaimed and translated worldwide.

Passionate about human movement outside of exercise, Katy volunteers her time to support the larger reintegration of movement into human lives by providing movement courses across widely varying demographics and working with non-profits promoting nature education. She also directs and teaches at the Nutritious Movement Center Northwest in Washington state, travels the globe to teach Nutritious Movement™ courses in person, and spends as much time outside as possible with her husband and children.

We talk about her social media break in the episode. To hear more about her break check out her episodes of Katy Says dedicated to the nitty-gritty of getting offline.

EPISODE 76 – KATY BOWMAN

FOLLOW KATY:

Website: www.nutritiousmovement.comFacebook: www.facebook.com/nutritiousmovement

Twitter: https://twitter.com/NutritiousMvmnt

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/nutritiousmovement/

No comments:

Post a Comment