Dehydration is one of the most overlooked and basic causes of disease.

Most people do not look at water as a nutrient but it is, and it is the most important one. We can live for a few months without food but will last only about 10 days without water. Next to the air we breathe water is the most important element. Every life-giving and healing process that happens inside our body happens with water. Most experts insist that the majority of Americans are chronically under-hydrated and should drink more water, and the reasons behind their insistence are solid.

Most people do not look at water as a nutrient but it is, and it is the most important one. We can live for a few months without food but will last only about 10 days without water. Next to the air we breathe water is the most important element. Every life-giving and healing process that happens inside our body happens with water. Most experts insist that the majority of Americans are chronically under-hydrated and should drink more water, and the reasons behind their insistence are solid.

Dr. Charles Peterson of NIH says dehydration is mainly a problem among Americans suffering from other illnesses, such as diabetes, or those who undergo extreme exertion, but this is not really true. Anyone can suffer from dehydration and the facts seem to point to the fact that most people suffer from mild dehydration at one time or another. Though everyone understands the vital importance of water, it is impossible to find solid information about dehydration statistics. On the Internet the consensus is that 75 percent of Americans are dehydrated but medical science does not weigh in on this statistic. We can assume that dehydration is a real problem, especially for those who believe that beverages like coffee and sodas can substitute for pure drinking water. Eating and drinking the wrong foods will lead to dehydration. Foods such as fruits and vegetables are supposed to provide 20 percent of our water intake – junk foods do little tohelp us remain fully hydrated. [1]

Thus under normal circumstances many of us flirt with mild dehydration over sustained periods. This is where things start to go wrong and doctors routinely make matters worse by not only failing to recognize dehydration but also by prescribing medicines that further depress water levels in the body and blood.

According to a study published in the Archives of Disease in Childhood, more than 70% of preschool children never drink plain water. Pediatric medicine does not pay attention enough to dehydration that occurs when acute diseases strike [2] and children can pay with their life for this if doctors then go ahead and administer vaccines when the blood is compromised. One of the most common lawsuits in pediatric emergency room medicine is overlooking dehydration; this tells us of a gaping hole in pediatric medicine that need not be there.

Shortness of breath is a common symptom of dehydration and when someone experiences this he merely has to drink several glasses of water to feel the body’s almost instant response to hydration. Add some sodium bicarbonate and the response is even greater.

The first objective sign of dehydration is seen in the vital signs, in an increase of the pulse rate between 10% and 15%. The body tries to maintain cardiac output (the amount of blood that is pumped by the heart to the body); and if the amount of fluid in the intravascular space is decreased, the body has to increase the heart rate, which causes blood vessels to constrict to maintain blood pressure. Other common symptoms of dehydration may include nausea, fatigue, headaches, dry mouth and reduced mental acuity.

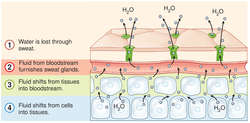

Symptoms of moderate to severe dehydration include:

Low blood pressure

Fainting

Severe muscle contractions in the arms, legs, stomach, and back

Convulsions

A bloated stomach

Heart failure

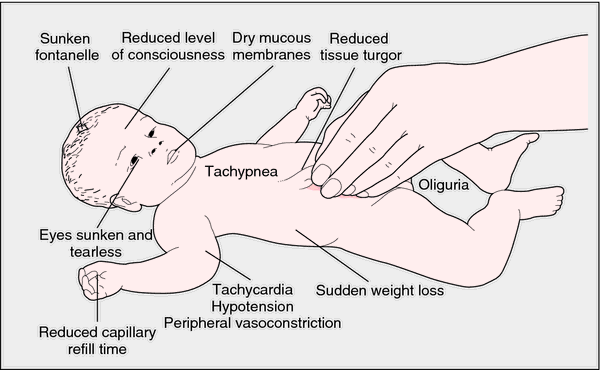

Sunken fontanelle– soft spot on a head

Sunken dry eyes, with few or no tears

Skin losing its firmness and becoming wrinkled

Lack of elasticity of the skin (when a bit of skin lifted up stays folded and takes a long time to go back to its normal position)

Rapid and deep breathing, faster than normal

Fast, weak pulse

Dehydration, the simple lack of sufficient quantities of water affects cell life profoundly. Water shortages in different parts of the body will manifest different signs and symptoms (cries of thirst), but we normally do not think to treat the cause of the problem with water. It is almost blasphemy among contemporary physicians to think that water can cause or cure diseases.

Drinking enough water is crucial and when we don’t drink enough, the first sign of that is darkening urine. The color of urine in a dehydrated person will be dark yellow to orange. The more hydrated we are the lighter the color of our urine. Any dark color at all in the urine could indicate a water deficiency.

Mild dehydration will slow down one’s metabolism as much as 3%. One glass of water shut down midnight hunger pangs for almost 100% of the dieters studied in a University of Washington study. Lack of water is the #1 trigger of daytime fatigue. Preliminary research indicates that 8-10 glasses of water a day could significantly ease back and joint pain for up to 80% of sufferers. Drinking five glasses of water daily decreases the risk of colon cancer by 45% and the risk of bladder cancer by 50%.

Dehydration is an underappreciated etiology in many diseases. Most doctors fail to understand – or refuse to consider – that water plays such a huge part in disease states probably because it is too common of a substance. Water is the first thing we should take as a medicine but physicians rarely prescribe water, and you’ll never hear of a pharmaceutical company recommending it, yet water can prevent and cure many common conditions because intake of sufficient amounts of it is a basic or underlying cause of disease.

From the perspective of Dr. F.Batmanghelidj [3], the famous water doctor, most so-called incurable diseases are nothing but labels given to various stages of chronic dehydration. In my work Natural Allopathic Medicine water is the most primary medicine and before one embarks on more radical medical approaches, full hydration with the best water one can manage is a good idea. According to Batmanghelidj, water can relieve a broad range of medical conditions. Bysimplyadjusting our fluid and mineral intakes we can treat and prevent dozens of diseases and avoid costly prescription drugs, surgery and other medical procedures and tests.

Dehydrated Cells

Cells are more vulnerable to chemical poisoning when in a dehydrated state. One overlooked factor in metabolic syndrome and inflammation is dehydration. When you do not drink enough water inflammation feels worse because it gets worse. Certainly dehydration is a contributing and complicating factor in diabetes.

When for any reason the body cannot deliver the necessary nutrients to the cells and carry away metabolic wastes, we set up the conditions for disease. Dehydration leads to damage from deterioration, because the transporting of nutrients and wastes is diminished and even cut off at strategic points in the body. One of the first protocols for a patient in the emergency room is an intravenous saline solution. Emergency room doctors are well aware that dehydration, second only to oxygen deprivation, robs life fastest.

Protoplasm, the basic material of living cells, is made of fats, carbohydrates, proteins, salts, and similar elements combined with water. Water acts as a solvent, transporting, combining, and chemically breaking down these substances. A cell exchanges elements with the rest of the body by electrolysis, and in a normal case, minerals and microelements pass through the cell membrane to the nucleus by electro-osmosis. The body needs electrolytes (minerals like sodium, potassium, chloride, and bicarbonate) for its basic functions.

The cells are made of water and they live in a water solution. Our blood is mostly water and serves to dissolve, process, and transport nutrients and eliminate waste materials. When dehydrated the blood becomes thick and saturated and is unable to flow freely. The excess of toxins must then be stored within the interstitial space surrounding the cells, pending elimination for life to continue, and over time this space begins to resemble a toxic waste site – an acidic medium. Since the cells cannot have the proper oxygenation and nutrition they begin to change in form and function in order to survive.

Dr. Sang Whang, author of the Reverse Aging , says the aging process is basically the accumulation of acidic wastes built up within the body. He says, “The nutrients that we deliver to our cells burn with oxygen and become acidic wastes after giving energy to our body. The body tries its best to get rid of these acidic wastes through urine and perspiration. Unfortunately, our lifestyle, diet and environment prevent our body to get rid of all the wastes that it generates. Gradually, these leftover acidic wastes accumulate somewhere within our body. Since acid coagulates blood, the blood circulation near the waste areas becomes poor, causing all kinds of degenerative diseases to develop…”

When the blood becomes concentrated and acidic, as in dehydration, then abrasions and tears are produced in the arterial system. L-lactic acidosis is thought to arise from poor tissue perfusion due to dehydration or endotoxaemia with subsequent anaerobic glycolysis and decreased hepatic clearance of L-lactate. We must look beyond what allopathic medicine thinks and see that the body makes more cholesterol in part as a reaction to chronic dehydration, a condition where the body is trying to fix these abrasions and tears that are produced in the arterial system. Cholesterol actually saves people’s lives because it acts as a bandage – a waterproof bandage – that the body has designed.

The body manifests dehydration in the form of pain with the location of the pain being the point or points where dehydration is most settled. Tests consistently reveal that chronic pain patients suffer from chronic dehydration. A significant number of these patients also have a lower than normal venous blood plasma pH. A person with low venous plasma pH has what is termed acid blood. Acid blood is typically dark in color due to low oxygen content. [Note: The body does whatever is necessary to maintain its blood pH within a narrow window – 7.35-7.45. If this level is not maintained, it is a serious medical emergency.

Painful joints are often a signal of water shortage, thus the use of painkillers does not cure the problem but instead exposes the person to further damage from these pain medications. Intake of water and small amounts of mineral salts will address this problem especially if that mineral is magnesium.

Dr. Norman Shealy says, “Every known illness is associated with a magnesium deficiency” and that, “magnesium is the most critical mineral required for electrical stability of every cell in the body. A magnesium deficiency may be responsible for more diseases than any other nutrient.”The benefits of drinking water are amplified immensely with water high in magnesium and bicarbonates.

Thus under normal circumstances many of us flirt with mild dehydration over sustained periods. This is where things start to go wrong and doctors routinely make matters worse by not only failing to recognize dehydration but also by prescribing medicines that further depress water levels in the body and blood.

According to a study published in the Archives of Disease in Childhood, more than 70% of preschool children never drink plain water. Pediatric medicine does not pay attention enough to dehydration that occurs when acute diseases strike [2] and children can pay with their life for this if doctors then go ahead and administer vaccines when the blood is compromised. One of the most common lawsuits in pediatric emergency room medicine is overlooking dehydration; this tells us of a gaping hole in pediatric medicine that need not be there.

Shortness of breath is a common symptom of dehydration and when someone experiences this he merely has to drink several glasses of water to feel the body’s almost instant response to hydration. Add some sodium bicarbonate and the response is even greater.

The first objective sign of dehydration is seen in the vital signs, in an increase of the pulse rate between 10% and 15%. The body tries to maintain cardiac output (the amount of blood that is pumped by the heart to the body); and if the amount of fluid in the intravascular space is decreased, the body has to increase the heart rate, which causes blood vessels to constrict to maintain blood pressure. Other common symptoms of dehydration may include nausea, fatigue, headaches, dry mouth and reduced mental acuity.

Symptoms of moderate to severe dehydration include:

Low blood pressure

Fainting

Severe muscle contractions in the arms, legs, stomach, and back

Convulsions

A bloated stomach

Heart failure

Sunken fontanelle– soft spot on a head

Sunken dry eyes, with few or no tears

Skin losing its firmness and becoming wrinkled

Lack of elasticity of the skin (when a bit of skin lifted up stays folded and takes a long time to go back to its normal position)

Rapid and deep breathing, faster than normal

Fast, weak pulse

Dehydration, the simple lack of sufficient quantities of water affects cell life profoundly. Water shortages in different parts of the body will manifest different signs and symptoms (cries of thirst), but we normally do not think to treat the cause of the problem with water. It is almost blasphemy among contemporary physicians to think that water can cause or cure diseases.

Drinking enough water is crucial and when we don’t drink enough, the first sign of that is darkening urine. The color of urine in a dehydrated person will be dark yellow to orange. The more hydrated we are the lighter the color of our urine. Any dark color at all in the urine could indicate a water deficiency.

Mild dehydration will slow down one’s metabolism as much as 3%. One glass of water shut down midnight hunger pangs for almost 100% of the dieters studied in a University of Washington study. Lack of water is the #1 trigger of daytime fatigue. Preliminary research indicates that 8-10 glasses of water a day could significantly ease back and joint pain for up to 80% of sufferers. Drinking five glasses of water daily decreases the risk of colon cancer by 45% and the risk of bladder cancer by 50%.

Dehydration is an underappreciated etiology in many diseases. Most doctors fail to understand – or refuse to consider – that water plays such a huge part in disease states probably because it is too common of a substance. Water is the first thing we should take as a medicine but physicians rarely prescribe water, and you’ll never hear of a pharmaceutical company recommending it, yet water can prevent and cure many common conditions because intake of sufficient amounts of it is a basic or underlying cause of disease.

From the perspective of Dr. F.Batmanghelidj [3], the famous water doctor, most so-called incurable diseases are nothing but labels given to various stages of chronic dehydration. In my work Natural Allopathic Medicine water is the most primary medicine and before one embarks on more radical medical approaches, full hydration with the best water one can manage is a good idea. According to Batmanghelidj, water can relieve a broad range of medical conditions. Bysimplyadjusting our fluid and mineral intakes we can treat and prevent dozens of diseases and avoid costly prescription drugs, surgery and other medical procedures and tests.

Dehydrated Cells

Cells are more vulnerable to chemical poisoning when in a dehydrated state. One overlooked factor in metabolic syndrome and inflammation is dehydration. When you do not drink enough water inflammation feels worse because it gets worse. Certainly dehydration is a contributing and complicating factor in diabetes.

When for any reason the body cannot deliver the necessary nutrients to the cells and carry away metabolic wastes, we set up the conditions for disease. Dehydration leads to damage from deterioration, because the transporting of nutrients and wastes is diminished and even cut off at strategic points in the body. One of the first protocols for a patient in the emergency room is an intravenous saline solution. Emergency room doctors are well aware that dehydration, second only to oxygen deprivation, robs life fastest.

Protoplasm, the basic material of living cells, is made of fats, carbohydrates, proteins, salts, and similar elements combined with water. Water acts as a solvent, transporting, combining, and chemically breaking down these substances. A cell exchanges elements with the rest of the body by electrolysis, and in a normal case, minerals and microelements pass through the cell membrane to the nucleus by electro-osmosis. The body needs electrolytes (minerals like sodium, potassium, chloride, and bicarbonate) for its basic functions.

The cells are made of water and they live in a water solution. Our blood is mostly water and serves to dissolve, process, and transport nutrients and eliminate waste materials. When dehydrated the blood becomes thick and saturated and is unable to flow freely. The excess of toxins must then be stored within the interstitial space surrounding the cells, pending elimination for life to continue, and over time this space begins to resemble a toxic waste site – an acidic medium. Since the cells cannot have the proper oxygenation and nutrition they begin to change in form and function in order to survive.

Dr. Sang Whang, author of the Reverse Aging , says the aging process is basically the accumulation of acidic wastes built up within the body. He says, “The nutrients that we deliver to our cells burn with oxygen and become acidic wastes after giving energy to our body. The body tries its best to get rid of these acidic wastes through urine and perspiration. Unfortunately, our lifestyle, diet and environment prevent our body to get rid of all the wastes that it generates. Gradually, these leftover acidic wastes accumulate somewhere within our body. Since acid coagulates blood, the blood circulation near the waste areas becomes poor, causing all kinds of degenerative diseases to develop…”

When the blood becomes concentrated and acidic, as in dehydration, then abrasions and tears are produced in the arterial system. L-lactic acidosis is thought to arise from poor tissue perfusion due to dehydration or endotoxaemia with subsequent anaerobic glycolysis and decreased hepatic clearance of L-lactate. We must look beyond what allopathic medicine thinks and see that the body makes more cholesterol in part as a reaction to chronic dehydration, a condition where the body is trying to fix these abrasions and tears that are produced in the arterial system. Cholesterol actually saves people’s lives because it acts as a bandage – a waterproof bandage – that the body has designed.

The body manifests dehydration in the form of pain with the location of the pain being the point or points where dehydration is most settled. Tests consistently reveal that chronic pain patients suffer from chronic dehydration. A significant number of these patients also have a lower than normal venous blood plasma pH. A person with low venous plasma pH has what is termed acid blood. Acid blood is typically dark in color due to low oxygen content. [Note: The body does whatever is necessary to maintain its blood pH within a narrow window – 7.35-7.45. If this level is not maintained, it is a serious medical emergency.

Painful joints are often a signal of water shortage, thus the use of painkillers does not cure the problem but instead exposes the person to further damage from these pain medications. Intake of water and small amounts of mineral salts will address this problem especially if that mineral is magnesium.

Dr. Norman Shealy says, “Every known illness is associated with a magnesium deficiency” and that, “magnesium is the most critical mineral required for electrical stability of every cell in the body. A magnesium deficiency may be responsible for more diseases than any other nutrient.”The benefits of drinking water are amplified immensely with water high in magnesium and bicarbonates.

REFERENCES:

[1] iceberg lettuce 96%

squash, cooked. 90%

cantaloupe, raw, 90%

2% milk 89%

apple, raw 86%

cottage cheese 76%

potato, baked 75%

macaroni, cooked 66%

turkey, roasted 62%

steak, cooked 50%

cheese, cheddar 37%

bread, white 36%

peanuts, dry roasted 2%

[2] Children and adults easily lose too much fluid from: Vomiting or diarrhea,excessive urine output, such as with uncontrolled diabetes or diuretic use,excessive sweating (for example, from exercise),fever. You might not drink enough fluids because of: nausea, loss of appetite due to illness,sore throat or mouth sores. Dehydration in sick children is often a combination of both – refusing to eat or drink anything while also losing fluid from vomiting, diarrhea, or fever.

[3] www.watercure.com

Dr. Mark Sircus

AC., OMD, DM (P)

Director International Medical Veritas Association

Doctor of Oriental and Pastoral Medicine

Definition:

Dehydration is the loss of water and salts essential for normal body function.

Description:

Dehydration occurs when the body loses more fluid than it takes in. This condition can result from illness; a hot, dry climate; prolonged exposure to sun or high temperatures; not drinking enough water; and overuse of diuretics or other medications that increase urination. Dehydration can upset the delicate fluid-salt balance needed to maintain healthy cells and tissues.

Water accounts for about 60% of a man's body weight. It represents about 50% of a woman's weight. Young and middle-aged adults who drink when they're thirsty do not generally have to do anything more to maintain their body's fluid balance. Children need more water because they expend more energy, but most children who drink when they are thirsty get as much water as their systems require.

Age and dehydration

Adults over the age of 60 who drink only when they are thirsty probably get only about 90% of the fluid they need. Developing a habit of drinking only in response to the body's thirst signals raises an older person's risk of becoming dehydrated. Seniors who have relocated to areas where the weather is warmer or dryer than the climate they are accustomed to are even likelier to become dehydrated unless they make it a practice to drink even when they are not thirsty.

Dehydration in children usually results from losing large amounts of fluid and not drinking enough water to replace the loss. This condition generally occurs in children who have stomach flu characterized by vomiting and diarrhea, or who can not or will not take enough fluids to compensate for excessive losses associated with fever and sweating of acute illness. An infant can become dehydrated only hours after becoming ill. Dehydration is a major cause of infant illness and death throughout the world.

Types of dehydration

Mild dehydration is the loss of no more than 5% of the body's fluid.

Loss of 5-10% is considered moderate dehydration.

Severe dehydration (loss of 10-15% of body fluids) is a life-threatening condition that requires immediate medical care.

Complications of dehydration

When the body's fluid supply is severely depleted, hypovolemic shock is likely to occur. This condition, which is also called physical collapse, is characterized by pale, cool, clammy skin; rapid heartbeat; and shallow breathing.

Blood pressure sometimes drops so low it can not be measured, and skin at the knees and elbows may become blotchy. Anxiety, restlessness, and thirst increase. After the patient's temperature reaches 107 °F (41.7 °C) damage to the brain and other vital organs occurs quickly.

Causes and symptoms

Strenuous activity, excessive sweating, high fever, and prolonged vomiting or diarrhea are common causes of dehydration. So are staying in the sun too long, not drinking enough fluids, and visiting or moving to a warm region where it doesn't often rain. Alcohol, caffeine, and diuretics or other medications that increase the amount of fluid excreted can cause dehydration.

Reduced fluid intake can be a result of:

>appetite loss associated with acute illness

>excessive urination (polyuria)

>nausea

>bacterial or viral infection or inflammation of the pharynx (pharyngitis)

>inflammation of the mouth caused by illness, infection, irritation, or vitamin deficiency (stomatitis)

Other conditions that can lead to dehydration include:

>disease of the adrenal glands, which regulate the body's water and salt balance and the function of many organ systems

>diabetes mellitus

>eating disorders

>kidney disease

>chronic lung disease.

An infant who does not wet a diaper in an eight-hour period is dehydrated. The soft spot on the baby's head (fontanel) may be depressed. Symptoms of dehydration at any age include cracked lips, dry or sticky mouth, lethargy, and sunken eyes. A person who is dehydrated cries without she shedding tears and does not urinate very often. The skin is less elastic than it should be and is slow to return to its normal position after being pinched.

Dehydration can cause confusion, constipation, discomfort, drowsiness, fever, and thirst. The skin turns pale and cold, the mucous membranes lining the mouth and nose lose their natural moisture. The pulse sometimes races and breathing becomes rapid. Significant fluid loss can cause serious neurological problems.

Diagnosis

The patient's symptoms and medical history usually suggest dehydration. Physical examination may reveal shock, rapid heart rate, and/or low blood pressure. Laboratory tests, including blood tests (to check electrolyte levels) and urine tests (e.g., urine specific gravity and creatinine), are used to evaluate the severity of the problem. Other laboratory tests may be ordered to determine the underlying condition (such as diabetes or an adrenal gland disorder) causing the dehydration.

Treatment

Increased fluid intake and replacement of lost electrolytes are usually sufficient to restore fluid balances in patients who are mildly or moderately dehydrated. For individuals who are mildly dehydrated, just drinking plain water may be all the treatment that is needed. Adults who need to replace lost electrolytes may drink sports beverages (e.g., Gatorade or Recharge) or consume a little additional salt. Parents should follow label instructions when giving children Pedialyte or other commercial products recommended to relieve dehydration. Children who are dehydrated should receive only clear fluids for the first 24 hours.

A child who is vomiting should sip one or two teaspoons of liquid every 10 minutes. A child who is less than a year old and who is not vomiting should be given one tablespoon of liquid every 20 minutes. A child who is more than one year old and who is not vomiting should take two tablespoons of liquid every 30 minutes. A baby who is being breast-fed should be given clear liquids for two consecutive feedings before breastfeeding is resumed. A bottle-fed baby should be given formula diluted to half its strength for the first 24 hours after developing symptoms of dehydration.

In order to accurately calculate fluid loss, it's important to chart weight changes every day and keep a record of how many times a patient vomits or has diarrhea. Parents should note how many times a baby's diaper must be changed.

Children and adults can gradually return to th their normal diet after they have stopped vomiting and no longer have diarrhea. Bland foods should be reintroduced first, with other foods added as the digestive system is able to tolerate them. Milk, ice cream, cheese, and butter should not be eaten until 72 hours after symptoms have disappeared.

Medical care

Severe dehydration can require hospitalization and intravenous fluid replacement. If an individual's blood pressure drops enough to cause or threaten the development of shock, medical treatment is usually required. A doctor should be notified whenever an infant or child exhibits signs of dehydration or a parent is concerned that a stomach virus or other acute illness may lead to dehydration.

a doctor should also be notified if:

>a child less than three months old develops a fever higher than 100 °F (37.8 °C)

>a child more than three months old develops a fever higher than 102 °F (38.9 °C)

>symptoms of dehydration worsen

>an individual urinates very sparingly or does not urinate at all during a six-hour period

>dizziness, listlessness, or excessive thirst occur

>a person who is dieting and using diuretics loses more than 3 lb (1.3 kg) in a day or more than 5 lb (2.3 kg) a week.

When treating dehydration, the underlying cause must also be addressed. For example, if dehydration is caused by vomiting or diarrhea, medications may be prescribed to resolve these symptoms. Patients who are dehydrated due to diabetes, kidney disease, or adrenal gland disorders must receive treatment for these conditions as well as for the resulting dehydration.

Alternative treatment

Gelatin water can be substituted for electrolyte-replacement solutions. It is made by diluting a 3-oz package in a quart of water or by adding one-quarter teaspoon of salt and a tablespoon of sugar to a pint of water.

Prognosis

Mild dehydration rarely results in complications. If the cause is eliminated and lost fluid is replaced, mild dehydration can usually be cured in 24-48 hours.

Vomiting and diarrhea that continue for several days without adequate fluid replacement can be fatal. The risk of life-threatening complications is greater for young children and the elderly. However, dehydration that is rapidly recognized and treated has a good outcome.

Prevention

Patients who are vomiting or who have diarrhea can prevent dehydration by drinking enough fluid for their urine to remain the color of pale straw. Ensuring that patients always drink adequate fluids during an illness will help prevent dehydration. Infants and young children with diarrhea and vomiting can be given electrolyte solutions such as Pedialyte to help prevent dehydration. People who are not ill can maintain proper fluid balance by drinking several glasses of water before going outside on a hot day. It is also a good idea to avoid coffee and tea, which increase body temperature and water loss.

Patients should know whether any medication they are taking can cause dehydration and should get prompt medical care to correct any underlying condition that increases the risk of dehydration.

Other methods of preventing dehydration and ensuring adequate fluid intake include:

>eating more soup at mealtime

>drinking plenty of water and juice at mealtime and between meals

>keeping a glass of water nearby when working or relaxing

Resources

Other

"Hydration—Getting Enough Water." Loyola University Health System. May 13, 1998. http://www.luhs.org.

Key terms

Electrolytes — Mineral salts, such as sodium and potassium, dissolved in body fluid.

Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Copyright 2008 The Gale Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

dehydration (de?hi?dra'shon) [ de- + hydration]

1. The removal of water from a chemical, e.g., by surface evaporation or by heating it to release water of crystallization. Synonym: anhydration

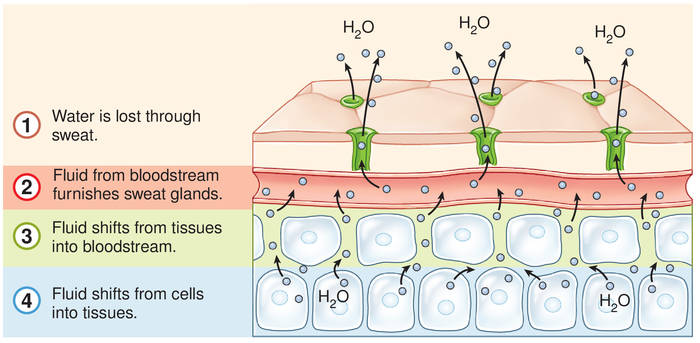

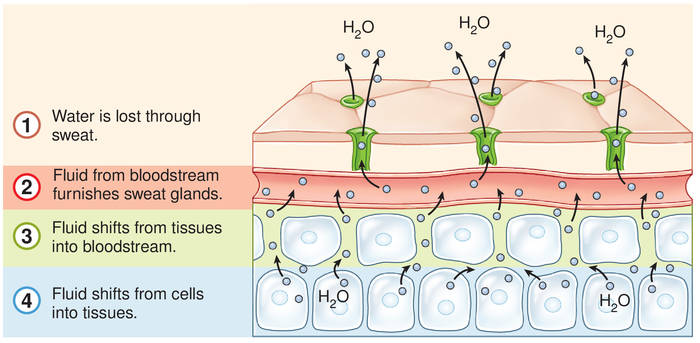

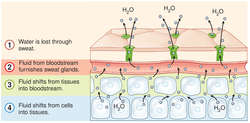

DEHYDRATION PROCESS

2. The clinical consequences of negative fluid balance, i.e., of fluid intake that fail to match fluid loss. Dehydration is marked by thirst, orthostatic hypotension, tachycardia, elevated plasma sodium levels, hyperosmolality, and, in severe instances, cellular disruption, delirium, falls, hyperthermia, medication toxicity, renal failure, or death. ; illustration

Etiology

Worldwide, the most common cause of dehydration is diarrhea. In industrialized nations, dehydration is also caused by vomiting, fevers, heat-related illnesses, diabetes mellitus, diuretic use, thyrotoxicosis, and hypercalcemia. Patients at risk for dehydration include those with an impaired level of consciousness and/or an inability to ingest oral fluids, patients receiving only high-protein enteral feedings, older adults who do not drink enough water, and patients (esp. infants and children) with watery diarrhea. The elderly (esp. those over 85) are increasingly hospitalized for dehydration. Dehydration is avoidable and preventable. Lengthy fasting before a procedure, long waits in emergency departments, or increased physical dependency (e.g., being unable to pour water from a bedside container) may place patients at risk. Nursing home residents are at higher risk for dehydration than older adults living independently, partly because of limited access to oral fluids. The elderly also are at risk because of reduced thirst-response, a decrease in total body fluids, and declining renal function. Clinical states that can produce hypertonicity and dehydration include a deficiency in synthesis or release of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) from the posterior pituitary gland (diabetes insipidus); a decrease in renal responsiveness to ADH; osmotic diuresis (hyperglycemic states, administration of osmotic diuretics); excessive pulmonary water loss from high fever (esp. in children); and excessive sweating without water replacement.

CAUTION!

Dehydration should not be confused with fluid volume deficit. In the latter condition, water and electrolytes are lost in the same proportion as they exist in normal body fluids; thus, the electrolyte to water ratio remains unchanged. In dehydration, water is the primary deficiency, resulting in increased levels of electrolytes or hypertonicity.

Patient care

The patient is assessed for decreased skin turgor; dry, sticky mucous membranes; rough, dry tongue; weight loss; fever; restlessness; agitation; and weakness. Cardiovascular findings include orthostatic hypotension, decreased cardiovascular pressure, and a rapid, weak pulse. Hard stools result if the patient's problem is not primarily watery diarrhea. Urinary findings include a decrease in urine volume (oliguria), specific gravity higher than 1.030, and an increase in urine osmolality. Blood serum studies reveal increased sodium, protein, hematocrit, and serum osmolality.

Continued loss of water is prevented, and water replacement is provided as prescribed, usually beginning with a 5% dextrose in water solution intravenously if the patient cannot ingest oral fluids. Once adequate renal function is present, electrolytes can be added to the infusion based upon periodic evaluation of serum electrolyte levels. Health care professionals can prevent dehydration by quickly treating causes such as vomiting and diarrhea, measuring fluid intake (and where possible urine output) in at-risk patients, providing glasses and cups that are light and easily handled, teaching certified nursing assistants (CNAs) and family care providers to record fluid intake, observing urine concentration in incontinent patients, offering fluids in small amounts every time they interact with an at-risk patient, encouraging increased amounts of fluids (at the patient’s preferred temperature) with and between meals and at bedtime (to 50 ounces or 1500 ml/D unless otherwise restricted), and offering preferred fluids and a variety of fluids (including frozen juice bars, water-rich fruits and vegetables), and assessing for excessive fluid loss during hot weather and replacing it.

Voluntary Dehydration

The willful refusal to eat, drink, or accept fluids from health care providers, sometimes used by the terminally ill to hasten death.

Medical Dictionary, © 2009 Farlex and Partners

dehydration A reduction in the normal water content of the body. This is usually due to excessive fluid loss by sweating, vomiting or diarrhoea which is not balanced by an appropriate increase in intake. Collins Dictionary of Medicine © Robert M. Youngson 2004, 2005

dehydration [de″hi-dra´shun]

removal of water from the body or a tissue; or the condition that results from undue loss of water. diarrhea in infants is a common cause of this. Severe dehydration is a serious condition that may lead to shock, acidosis, and accumulation of waste products in the body (as in uremia), sometimes resulting in death. Water accounts for more than half the body weight. Under normal conditions, the total 24-hour output of fluid in urine and feces and through the lungs and skin is about 2500 ml in adults. To make up for this loss, the same amount must be taken in to maintain fluid balance. When the fluid intake is insufficient or the output is excessive, deficient fluid volume occurs.

Patient discussion about dehydration

Q. What Are The Signs of Dehydration? How can you tell if someone is dehydrated? Are there specific signs or symptoms that may help notice?

A. To that I really notice when I am.... When you first stand up you feel dizzy, yet when you lay down you feel fine. My eyes sink back into their sockets.

Q. Why does headaches are a symptom of dehydration? A few days ago I had a headache and a friend told me that I’m probably dehydrated and I should drink more water. So I did and the headache was gone…how come? What is the connection?

A. Headaches usually come from the tissues surrounding the brain. The brain itself can not feel pain. The tissues surrounding the brain (meningia) are filled with fluid named- Cerebro Spinal Fluid (CSF), when you are dehydrated the brain has a lot less liquid that will stand as a buffer between him and the skull. Thus every movement your head does will create pressure on the meningia and that hurts.

Q. I heard that the major risk in diarrhea is dehydration, why is that? How can I avoid that? Are there other dehydration causes I should beware of?

A. Vomiting will also dehydrate you about as dangerously as diarrhea .

dehydration

the state when the body loses more water than it takes in. There is a negative fluid balance, so that the circulating blood volume decreases and tissue fluids are reduced and tissues are dehydrated. The clinical syndrome of dehydration includes loosening and wrinkling of the skin, and a bad skin-tenting reaction, in which a pinched-up fold of skin takes longer than normal to disappear; there is usually evidence of the cause of the dehydration, e.g. vomiting, polyuria. Clinical pathological tests are essential to determine the severity of the dehydration.

cellular dehydration caused by increased osmoconcentration of the extracellular fluid.

dehydration (dē´hīdrā´shən),

n 1. the removal of water (e.g., from the body or tissue).

n 2. a decrease in serum fluid coupled with the loss of interstitial fluid from the body. It is associated with disturbances in fluid and electrolyte balance.

dehydration of gingivae,

n the drying of gingival tissue, leading to a lowered tissue resistance, which can result in gingival inflammation; seen in mouth breathing. See also breathing, mouth and oral cavity.

de·hy·dra·tion (dē-hī-drā'shŭn) Avoid the jargonistic use of this word as a synonym of thirst.

1. Deprivation of water.

2. Reduction of water content.

3. Synonym(s): exsiccation.

4. Used in emergency departments to describe a state of water loss sufficient to cause intravascular volume deficits leading to orthostatic symptoms.

dehydration in general, the process of removal or loss of water from a substance or body. For related terms used in the context of human fluid balance, see also hydration status.

dehydration the process by which water is removed from any substance. It is utilized in freeze-drying for the preservation of materials, and in the removal of water from microscopical preparations where it is necessary to use substances which are immiscible with water.

dehydration A reduction in the normal water content of the body. This is usually due to excessive fluid loss by sweating, vomiting or diarrhea which is not balanced by an appropriate increase in intake.

dehydration Internal medicine The loss of intracellular water that leads to cellular desiccation and ↑ plasma sodium concentration and osmolality, often due to GI tract–eg, vomiting, diarrhea Clinical Rapid ↓ weight loss of 10% is severe, ↑ thirst, dry mouth, weakness or lightheadedness, worse on standing, darkened or ↓ urine; severe dehydration can lead to changes in the body chemistry, kidney failure, ±life-threatening Management Fluid replacement, 5% dextrose. Cf Volume depletion. volume depletion Internal medicine A state of vascular instability characterized by ↓ sodium in the extracellular space–intravascular and interstitial fluid after GI hemorrhage, vomiting, diarrhea, diuresis Management 0.9% saline ASAP. Cf Dehydration, Fluid overload.

volume depletion

Loss of body fluids, e.g., by bleeding, sweating, urinating, or vomiting. Excessive loss of body fluids without replenishment results in dehydration, hypotension, and kidney failure.

dehydration

[di′hīdrā′shən]

1 excessive loss of water from body tissues. Dehydration is accompanied by a disturbance in the balance of essential electrolytes, particularly sodium, potassium, and chloride. It may follow prolonged fever, diarrhea, vomiting, acidosis, and any condition in which there is rapid depletion of body fluids. It is of particular concern among infants and young children because their electrolyte balance is normally precarious. Signs of dehydration include poor skin turgor (not a reliable sign in the elderly), flushed dry skin, coated tongue, dry mucous membranes, oliguria, irritability, and confusion. Normal fluid volume and balanced electrolyte values are the primary goals of therapy.

2 rendering a substance free from water. Also called anhydration.

[1] iceberg lettuce 96%

squash, cooked. 90%

cantaloupe, raw, 90%

2% milk 89%

apple, raw 86%

cottage cheese 76%

potato, baked 75%

macaroni, cooked 66%

turkey, roasted 62%

steak, cooked 50%

cheese, cheddar 37%

bread, white 36%

peanuts, dry roasted 2%

[2] Children and adults easily lose too much fluid from: Vomiting or diarrhea,excessive urine output, such as with uncontrolled diabetes or diuretic use,excessive sweating (for example, from exercise),fever. You might not drink enough fluids because of: nausea, loss of appetite due to illness,sore throat or mouth sores. Dehydration in sick children is often a combination of both – refusing to eat or drink anything while also losing fluid from vomiting, diarrhea, or fever.

[3] www.watercure.com

Dr. Mark Sircus

AC., OMD, DM (P)

Director International Medical Veritas Association

Doctor of Oriental and Pastoral Medicine

Definition:

Dehydration is the loss of water and salts essential for normal body function.

Description:

Dehydration occurs when the body loses more fluid than it takes in. This condition can result from illness; a hot, dry climate; prolonged exposure to sun or high temperatures; not drinking enough water; and overuse of diuretics or other medications that increase urination. Dehydration can upset the delicate fluid-salt balance needed to maintain healthy cells and tissues.

Water accounts for about 60% of a man's body weight. It represents about 50% of a woman's weight. Young and middle-aged adults who drink when they're thirsty do not generally have to do anything more to maintain their body's fluid balance. Children need more water because they expend more energy, but most children who drink when they are thirsty get as much water as their systems require.

Age and dehydration

Adults over the age of 60 who drink only when they are thirsty probably get only about 90% of the fluid they need. Developing a habit of drinking only in response to the body's thirst signals raises an older person's risk of becoming dehydrated. Seniors who have relocated to areas where the weather is warmer or dryer than the climate they are accustomed to are even likelier to become dehydrated unless they make it a practice to drink even when they are not thirsty.

Dehydration in children usually results from losing large amounts of fluid and not drinking enough water to replace the loss. This condition generally occurs in children who have stomach flu characterized by vomiting and diarrhea, or who can not or will not take enough fluids to compensate for excessive losses associated with fever and sweating of acute illness. An infant can become dehydrated only hours after becoming ill. Dehydration is a major cause of infant illness and death throughout the world.

Types of dehydration

Mild dehydration is the loss of no more than 5% of the body's fluid.

Loss of 5-10% is considered moderate dehydration.

Severe dehydration (loss of 10-15% of body fluids) is a life-threatening condition that requires immediate medical care.

Complications of dehydration

When the body's fluid supply is severely depleted, hypovolemic shock is likely to occur. This condition, which is also called physical collapse, is characterized by pale, cool, clammy skin; rapid heartbeat; and shallow breathing.

Blood pressure sometimes drops so low it can not be measured, and skin at the knees and elbows may become blotchy. Anxiety, restlessness, and thirst increase. After the patient's temperature reaches 107 °F (41.7 °C) damage to the brain and other vital organs occurs quickly.

Causes and symptoms

Strenuous activity, excessive sweating, high fever, and prolonged vomiting or diarrhea are common causes of dehydration. So are staying in the sun too long, not drinking enough fluids, and visiting or moving to a warm region where it doesn't often rain. Alcohol, caffeine, and diuretics or other medications that increase the amount of fluid excreted can cause dehydration.

Reduced fluid intake can be a result of:

>appetite loss associated with acute illness

>excessive urination (polyuria)

>nausea

>bacterial or viral infection or inflammation of the pharynx (pharyngitis)

>inflammation of the mouth caused by illness, infection, irritation, or vitamin deficiency (stomatitis)

Other conditions that can lead to dehydration include:

>disease of the adrenal glands, which regulate the body's water and salt balance and the function of many organ systems

>diabetes mellitus

>eating disorders

>kidney disease

>chronic lung disease.

An infant who does not wet a diaper in an eight-hour period is dehydrated. The soft spot on the baby's head (fontanel) may be depressed. Symptoms of dehydration at any age include cracked lips, dry or sticky mouth, lethargy, and sunken eyes. A person who is dehydrated cries without she shedding tears and does not urinate very often. The skin is less elastic than it should be and is slow to return to its normal position after being pinched.

Dehydration can cause confusion, constipation, discomfort, drowsiness, fever, and thirst. The skin turns pale and cold, the mucous membranes lining the mouth and nose lose their natural moisture. The pulse sometimes races and breathing becomes rapid. Significant fluid loss can cause serious neurological problems.

Diagnosis

The patient's symptoms and medical history usually suggest dehydration. Physical examination may reveal shock, rapid heart rate, and/or low blood pressure. Laboratory tests, including blood tests (to check electrolyte levels) and urine tests (e.g., urine specific gravity and creatinine), are used to evaluate the severity of the problem. Other laboratory tests may be ordered to determine the underlying condition (such as diabetes or an adrenal gland disorder) causing the dehydration.

Treatment

Increased fluid intake and replacement of lost electrolytes are usually sufficient to restore fluid balances in patients who are mildly or moderately dehydrated. For individuals who are mildly dehydrated, just drinking plain water may be all the treatment that is needed. Adults who need to replace lost electrolytes may drink sports beverages (e.g., Gatorade or Recharge) or consume a little additional salt. Parents should follow label instructions when giving children Pedialyte or other commercial products recommended to relieve dehydration. Children who are dehydrated should receive only clear fluids for the first 24 hours.

A child who is vomiting should sip one or two teaspoons of liquid every 10 minutes. A child who is less than a year old and who is not vomiting should be given one tablespoon of liquid every 20 minutes. A child who is more than one year old and who is not vomiting should take two tablespoons of liquid every 30 minutes. A baby who is being breast-fed should be given clear liquids for two consecutive feedings before breastfeeding is resumed. A bottle-fed baby should be given formula diluted to half its strength for the first 24 hours after developing symptoms of dehydration.

In order to accurately calculate fluid loss, it's important to chart weight changes every day and keep a record of how many times a patient vomits or has diarrhea. Parents should note how many times a baby's diaper must be changed.

Children and adults can gradually return to th their normal diet after they have stopped vomiting and no longer have diarrhea. Bland foods should be reintroduced first, with other foods added as the digestive system is able to tolerate them. Milk, ice cream, cheese, and butter should not be eaten until 72 hours after symptoms have disappeared.

Medical care

Severe dehydration can require hospitalization and intravenous fluid replacement. If an individual's blood pressure drops enough to cause or threaten the development of shock, medical treatment is usually required. A doctor should be notified whenever an infant or child exhibits signs of dehydration or a parent is concerned that a stomach virus or other acute illness may lead to dehydration.

a doctor should also be notified if:

>a child less than three months old develops a fever higher than 100 °F (37.8 °C)

>a child more than three months old develops a fever higher than 102 °F (38.9 °C)

>symptoms of dehydration worsen

>an individual urinates very sparingly or does not urinate at all during a six-hour period

>dizziness, listlessness, or excessive thirst occur

>a person who is dieting and using diuretics loses more than 3 lb (1.3 kg) in a day or more than 5 lb (2.3 kg) a week.

When treating dehydration, the underlying cause must also be addressed. For example, if dehydration is caused by vomiting or diarrhea, medications may be prescribed to resolve these symptoms. Patients who are dehydrated due to diabetes, kidney disease, or adrenal gland disorders must receive treatment for these conditions as well as for the resulting dehydration.

Alternative treatment

Gelatin water can be substituted for electrolyte-replacement solutions. It is made by diluting a 3-oz package in a quart of water or by adding one-quarter teaspoon of salt and a tablespoon of sugar to a pint of water.

Prognosis

Mild dehydration rarely results in complications. If the cause is eliminated and lost fluid is replaced, mild dehydration can usually be cured in 24-48 hours.

Vomiting and diarrhea that continue for several days without adequate fluid replacement can be fatal. The risk of life-threatening complications is greater for young children and the elderly. However, dehydration that is rapidly recognized and treated has a good outcome.

Prevention

Patients who are vomiting or who have diarrhea can prevent dehydration by drinking enough fluid for their urine to remain the color of pale straw. Ensuring that patients always drink adequate fluids during an illness will help prevent dehydration. Infants and young children with diarrhea and vomiting can be given electrolyte solutions such as Pedialyte to help prevent dehydration. People who are not ill can maintain proper fluid balance by drinking several glasses of water before going outside on a hot day. It is also a good idea to avoid coffee and tea, which increase body temperature and water loss.

Patients should know whether any medication they are taking can cause dehydration and should get prompt medical care to correct any underlying condition that increases the risk of dehydration.

Other methods of preventing dehydration and ensuring adequate fluid intake include:

>eating more soup at mealtime

>drinking plenty of water and juice at mealtime and between meals

>keeping a glass of water nearby when working or relaxing

Resources

Other

"Hydration—Getting Enough Water." Loyola University Health System. May 13, 1998. http://www.luhs.org.

Key terms

Electrolytes — Mineral salts, such as sodium and potassium, dissolved in body fluid.

Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Copyright 2008 The Gale Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

dehydration (de?hi?dra'shon) [ de- + hydration]

1. The removal of water from a chemical, e.g., by surface evaporation or by heating it to release water of crystallization. Synonym: anhydration

DEHYDRATION PROCESS

2. The clinical consequences of negative fluid balance, i.e., of fluid intake that fail to match fluid loss. Dehydration is marked by thirst, orthostatic hypotension, tachycardia, elevated plasma sodium levels, hyperosmolality, and, in severe instances, cellular disruption, delirium, falls, hyperthermia, medication toxicity, renal failure, or death. ; illustration

Etiology

Worldwide, the most common cause of dehydration is diarrhea. In industrialized nations, dehydration is also caused by vomiting, fevers, heat-related illnesses, diabetes mellitus, diuretic use, thyrotoxicosis, and hypercalcemia. Patients at risk for dehydration include those with an impaired level of consciousness and/or an inability to ingest oral fluids, patients receiving only high-protein enteral feedings, older adults who do not drink enough water, and patients (esp. infants and children) with watery diarrhea. The elderly (esp. those over 85) are increasingly hospitalized for dehydration. Dehydration is avoidable and preventable. Lengthy fasting before a procedure, long waits in emergency departments, or increased physical dependency (e.g., being unable to pour water from a bedside container) may place patients at risk. Nursing home residents are at higher risk for dehydration than older adults living independently, partly because of limited access to oral fluids. The elderly also are at risk because of reduced thirst-response, a decrease in total body fluids, and declining renal function. Clinical states that can produce hypertonicity and dehydration include a deficiency in synthesis or release of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) from the posterior pituitary gland (diabetes insipidus); a decrease in renal responsiveness to ADH; osmotic diuresis (hyperglycemic states, administration of osmotic diuretics); excessive pulmonary water loss from high fever (esp. in children); and excessive sweating without water replacement.

CAUTION!

Dehydration should not be confused with fluid volume deficit. In the latter condition, water and electrolytes are lost in the same proportion as they exist in normal body fluids; thus, the electrolyte to water ratio remains unchanged. In dehydration, water is the primary deficiency, resulting in increased levels of electrolytes or hypertonicity.

Patient care

The patient is assessed for decreased skin turgor; dry, sticky mucous membranes; rough, dry tongue; weight loss; fever; restlessness; agitation; and weakness. Cardiovascular findings include orthostatic hypotension, decreased cardiovascular pressure, and a rapid, weak pulse. Hard stools result if the patient's problem is not primarily watery diarrhea. Urinary findings include a decrease in urine volume (oliguria), specific gravity higher than 1.030, and an increase in urine osmolality. Blood serum studies reveal increased sodium, protein, hematocrit, and serum osmolality.

Continued loss of water is prevented, and water replacement is provided as prescribed, usually beginning with a 5% dextrose in water solution intravenously if the patient cannot ingest oral fluids. Once adequate renal function is present, electrolytes can be added to the infusion based upon periodic evaluation of serum electrolyte levels. Health care professionals can prevent dehydration by quickly treating causes such as vomiting and diarrhea, measuring fluid intake (and where possible urine output) in at-risk patients, providing glasses and cups that are light and easily handled, teaching certified nursing assistants (CNAs) and family care providers to record fluid intake, observing urine concentration in incontinent patients, offering fluids in small amounts every time they interact with an at-risk patient, encouraging increased amounts of fluids (at the patient’s preferred temperature) with and between meals and at bedtime (to 50 ounces or 1500 ml/D unless otherwise restricted), and offering preferred fluids and a variety of fluids (including frozen juice bars, water-rich fruits and vegetables), and assessing for excessive fluid loss during hot weather and replacing it.

Voluntary Dehydration

The willful refusal to eat, drink, or accept fluids from health care providers, sometimes used by the terminally ill to hasten death.

Medical Dictionary, © 2009 Farlex and Partners

dehydration A reduction in the normal water content of the body. This is usually due to excessive fluid loss by sweating, vomiting or diarrhoea which is not balanced by an appropriate increase in intake. Collins Dictionary of Medicine © Robert M. Youngson 2004, 2005

dehydration [de″hi-dra´shun]

removal of water from the body or a tissue; or the condition that results from undue loss of water. diarrhea in infants is a common cause of this. Severe dehydration is a serious condition that may lead to shock, acidosis, and accumulation of waste products in the body (as in uremia), sometimes resulting in death. Water accounts for more than half the body weight. Under normal conditions, the total 24-hour output of fluid in urine and feces and through the lungs and skin is about 2500 ml in adults. To make up for this loss, the same amount must be taken in to maintain fluid balance. When the fluid intake is insufficient or the output is excessive, deficient fluid volume occurs.

Patient discussion about dehydration

Q. What Are The Signs of Dehydration? How can you tell if someone is dehydrated? Are there specific signs or symptoms that may help notice?

A. To that I really notice when I am.... When you first stand up you feel dizzy, yet when you lay down you feel fine. My eyes sink back into their sockets.

Q. Why does headaches are a symptom of dehydration? A few days ago I had a headache and a friend told me that I’m probably dehydrated and I should drink more water. So I did and the headache was gone…how come? What is the connection?

A. Headaches usually come from the tissues surrounding the brain. The brain itself can not feel pain. The tissues surrounding the brain (meningia) are filled with fluid named- Cerebro Spinal Fluid (CSF), when you are dehydrated the brain has a lot less liquid that will stand as a buffer between him and the skull. Thus every movement your head does will create pressure on the meningia and that hurts.

Q. I heard that the major risk in diarrhea is dehydration, why is that? How can I avoid that? Are there other dehydration causes I should beware of?

A. Vomiting will also dehydrate you about as dangerously as diarrhea .

dehydration

the state when the body loses more water than it takes in. There is a negative fluid balance, so that the circulating blood volume decreases and tissue fluids are reduced and tissues are dehydrated. The clinical syndrome of dehydration includes loosening and wrinkling of the skin, and a bad skin-tenting reaction, in which a pinched-up fold of skin takes longer than normal to disappear; there is usually evidence of the cause of the dehydration, e.g. vomiting, polyuria. Clinical pathological tests are essential to determine the severity of the dehydration.

cellular dehydration caused by increased osmoconcentration of the extracellular fluid.

dehydration (dē´hīdrā´shən),

n 1. the removal of water (e.g., from the body or tissue).

n 2. a decrease in serum fluid coupled with the loss of interstitial fluid from the body. It is associated with disturbances in fluid and electrolyte balance.

dehydration of gingivae,

n the drying of gingival tissue, leading to a lowered tissue resistance, which can result in gingival inflammation; seen in mouth breathing. See also breathing, mouth and oral cavity.

de·hy·dra·tion (dē-hī-drā'shŭn) Avoid the jargonistic use of this word as a synonym of thirst.

1. Deprivation of water.

2. Reduction of water content.

3. Synonym(s): exsiccation.

4. Used in emergency departments to describe a state of water loss sufficient to cause intravascular volume deficits leading to orthostatic symptoms.

dehydration in general, the process of removal or loss of water from a substance or body. For related terms used in the context of human fluid balance, see also hydration status.

dehydration the process by which water is removed from any substance. It is utilized in freeze-drying for the preservation of materials, and in the removal of water from microscopical preparations where it is necessary to use substances which are immiscible with water.

dehydration A reduction in the normal water content of the body. This is usually due to excessive fluid loss by sweating, vomiting or diarrhea which is not balanced by an appropriate increase in intake.

dehydration Internal medicine The loss of intracellular water that leads to cellular desiccation and ↑ plasma sodium concentration and osmolality, often due to GI tract–eg, vomiting, diarrhea Clinical Rapid ↓ weight loss of 10% is severe, ↑ thirst, dry mouth, weakness or lightheadedness, worse on standing, darkened or ↓ urine; severe dehydration can lead to changes in the body chemistry, kidney failure, ±life-threatening Management Fluid replacement, 5% dextrose. Cf Volume depletion. volume depletion Internal medicine A state of vascular instability characterized by ↓ sodium in the extracellular space–intravascular and interstitial fluid after GI hemorrhage, vomiting, diarrhea, diuresis Management 0.9% saline ASAP. Cf Dehydration, Fluid overload.

volume depletion

Loss of body fluids, e.g., by bleeding, sweating, urinating, or vomiting. Excessive loss of body fluids without replenishment results in dehydration, hypotension, and kidney failure.

dehydration

[di′hīdrā′shən]

1 excessive loss of water from body tissues. Dehydration is accompanied by a disturbance in the balance of essential electrolytes, particularly sodium, potassium, and chloride. It may follow prolonged fever, diarrhea, vomiting, acidosis, and any condition in which there is rapid depletion of body fluids. It is of particular concern among infants and young children because their electrolyte balance is normally precarious. Signs of dehydration include poor skin turgor (not a reliable sign in the elderly), flushed dry skin, coated tongue, dry mucous membranes, oliguria, irritability, and confusion. Normal fluid volume and balanced electrolyte values are the primary goals of therapy.

2 rendering a substance free from water. Also called anhydration.

No comments:

Post a Comment